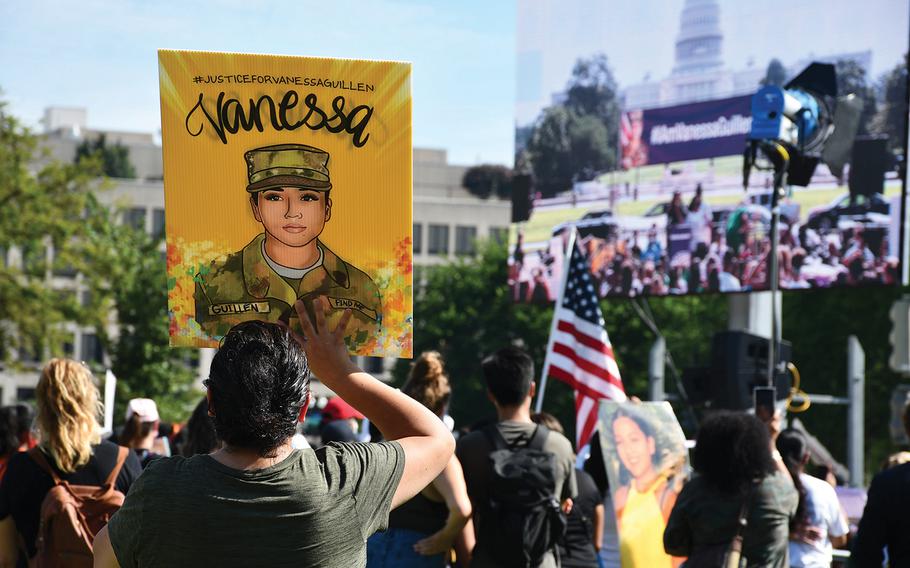

Activists held signs depicting Spc. Vanessa Guillen at a rally July 30, 2020, in Washington, D.C. Guillen's family said the soldier, who was killed in April 2020 at Fort Hood, Texas, told them that she was being sexually harassed but was too afraid to report it. (Nikki Wentling/Stars and Stripes)

The family of Spc. Vanessa Guillen, the soldier killed at Fort Hood last year, wants the Army to court-martial the platoon sergeant who was found to have sexually harassed her prior to her death.

The request came as part of their call for the service to hold Army leaders more accountable for their actions and advocate for a measure to make sexual harassment a standalone crime in the military.

Guillen’s death led to multiple investigations into the Army base in Texas and as a result roughly 21 leaders were targeted for punishment. However, much of that discipline has gone through the nonjudicial channels, which has shielded many of the final outcomes from the public due to privacy policies.

A court-martial would generate publicly available documents showing whether a leader was punished and to what extent.

“One of the most important parts of this case is the need for change and accountability and justice for Vanessa,” Natalie Khawam, an attorney for Guillen’s family, said this month after she and the family met with Gen. John Murray, who led an administrative investigation into Guillen’s chain of command.

Khawam and other legal experts agree the Uniform Code of Military Justice already allows the military to prosecute sexual harassment through a court-martial, but commanders rarely choose judicial punishment in those cases.

In Guillen’s case, the Army determined through an administrative investigation, known as a 15-6, that she was sexually harassed on two instances by a noncommissioned officer serving as her platoon sergeant within the 3rd Cavalry Regiment. For now, the sergeant, who has not been named by the Army, faces nonjudicial punishment, the results of which can remain hidden because it’s considered a personnel matter that is not available through public records.

That disconnect between founded allegations of sexual harassment and prosecution of them under the UCMJ, the federal law enacted by Congress that defines the military justice system and criminal offenses, shows why a separate crime is needed, said Meghan Tokash, a member of the Pentagon’s Independent Review Commission on Sexual Assault and Harassment.

“We know the military is not doing a good job of charging sexual harassment under the current construct,” said Tokash, a former Army special victim prosecutor who couldn’t recall any cases from her time in service that had sexual harassment as the lone charge against a defendant.

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin established the commission in February and tasked it with reviewing the military’s handling of these types of incidents. After a 90-day review, the commission recommended making sexual harassment a standalone crime among more than 80 other recommendations in its report released July 2.

Congress has the power to add crimes, known as articles, to the UCMJ and last did so in 2016, when it added Article 132 to prosecute retaliation.

“I think having a standalone article shows the importance of the crime of sexual harassment. What we know as prosecutors and what the [commission] was able to hear for the past three months, is that sexual harassment is typically the precursor to more serious crimes, including sexual assault and touching offenses,” Tokash said. “Much of sexual harassment can be stopped through preventative measures, so the introduction of a standalone article is a good thing for not only victims of sexual harassment but for military justice.”

Political pressure

A Rand Corp. report released this month estimated about 1 in 4 women and 1 in 16 men serving in the military experience sexual harassment. Those statistics have remained relatively unchanged for the past decade despite the Defense Department creating several measures and programs to combat sexual harassment and sexual assault among service members. Combined with the findings of recent investigations, it has led to more members of Congress supporting drastic change.

In the Guillen case, Tokash said she saw enough evidence in publicly available reports to use UCMJ Article 93, which already exists and references cruelty and/or maltreatment of subordinates. Other existing articles that could be used to charge sexual harassment include Articles 92, 133 and 134, Tokash said. Respectively, those articles address the failure to obey an order or regulation, conduct unbecoming of an officer and the general article, which encompasses behavior not mentioned in other articles that impacts good order and discipline.

Article 93 is most applicable to Guillen because the noncommissioned officer accused of harassing Guillen was her platoon sergeant and her supervisor, Tokash said.

Guillen went missing from Fort Hood on April 22, 2020, and her body was found buried about 20 miles from the base after a more than two-month search. It is believed she was killed by fellow soldier, Spc. Aaron Robinson, who died by suicide after her body was found.

During the search for Guillen, her family said she faced sexual harassment on base, but the soldier was too afraid to report it. In response, the Army conducted two investigations into the Texas base, one internal and another by an independent committee.

The internal investigation found Guillen’s platoon sergeant was a known toxic leader and he harassed Guillen on two instances. The sergeant was notified of an intent to relieve him from leadership, which triggered an evaluation, according to a military official who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Fort Hood officials declined to comment on whether a court-martial was ever under consideration for him, citing a policy not to speculate on military judicial actions.

Under an intent to relieve, the accused has an opportunity to dispute and respond to the allegations, which he has, said Robert Capovilla, a Georgia-based defense attorney representing the sergeant.

“While we are heartbroken for Spc. Guillen’s family and join in their quest for justice for her, we must also set the record straight regarding improper and inaccurate comments made by Army leadership, the release of an incomplete executive summary that omitted important details, and slanted media coverage. Justice demands this clarification as the future of a dedicated combat veteran with more than 14 years of service to our country is in jeopardy,” Capovilla, a former Army judge advocate, wrote in a letter addressed to all “reviewing authorities” that he provided to Stars and Stripes.

Capovilla also said, in general terms, based on his active-duty service and as a defense attorney who represents service members, the addition of the sexual harassment charge to the UCMJ could reduce the ambiguity of existing means to charge harassment as a crime. However, he said he fears the issue has become mired in politics.

“My concern is we're going to forget about the rights of the accused in this process, and I think that's a fundamental aspect of who we are as a country. That doesn't mean that victims shouldn't have a voice,” Capovilla said. “I'm afraid that innocent men and women are going to be put behind bars because of a political pressure being put on commanders.”

Discretion and transparency

For that reason, Capovilla said he supports another push in Congress to move court-martial proceedings for sex crimes from commanders and into the hands of special prosecutors. Austin came out in favor of this proposal following its recommendation by the independent review commission.

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., has pushed for this reform since 2013, but after Guillen’s death and the subsequent investigations, there now could be enough support in both chambers of Congress to get the measure passed. Guillen’s family has worked with Rep. Jackie Speier, D-Calif., on similar measures in the House, which are named in honor of the soldier.

While the Gillibrand and Speier bills would put prosecution decisions for all felony crimes in the hands of an independent prosecutor, Austin has only called for independent decisions outside the military chain of command for sexual assault, domestic violence, child abuse and retaliation.

Last week, the Senate Armed Services Committee passed its draft of the 2022 National Defense Authorization Act, which annually sets priorities and spending for the Defense Department. It included Gillibrand’s bill in full.

Rachel VanLandingham, a former Air Force judge advocate turned professor at Southwestern Law School in California, said she would like to see additional transparency added to the system as reforms are made because it is a commander’s discretion that has clouded the ability to understand decision-making and accountability.

Even a short, publicly released memorandum could help provide understanding and guide future decisions, VanLandingham said. Victims, including the Guillen family, are often left with no explanation why their perpetrators are dealt with in a nonjudiciary system instead of through the court-martial process.

Those making prosecutorial decisions need discretion to avoid the damage that a one-size-fits-all approach to discipline can have, but it can also lead to intentional and unintentional abuse, she said.

“We're all human and there's implied bias,” VanLandingham said. “The lower you go down in the spectrum of disciplinary measure from court-martial … all the way down to letter of reprimand, the greater that disparity, because there's less transparency.”

After the Army announced disciplinary action for about 21 leaders at Fort Hood following the release of two investigations into the base, actions taken against those leaders included removal from leadership positions, general officer memorandums of reprimand and letters of reprimand. Army leaders did not disclose why each disciplinary action was chosen for each person.

Rep. Sylvia Garcia, D-Texas, who represents the district where the Guillen family lives, said based on her conversations with Army leaders, the number of people disciplined is actually 13.

Each of the disciplinary actions taken allows for the soldier to contest the action and includes a review period. Some could result in a discharge from service, but that has not happened yet at Fort Hood, Khawam said.

“They have less responsibility, they are not in command anymore, but they’re still getting paid for a commanding position,” she said. “It’s unfair to watch perpetrators and wrongdoers continue to sit and exist in the Army system because all you are doing is moving them from one base to another. That’s not fixing the problem.”

Repeat offenders

In some instances, a general officer memorandum of reprimand, known as a GOMOR, is only included in a service member’s local file, which means when the person moves to their next duty station, the letter does not travel with them.

“If you sexually harassed someone, a fellow service member, there is no way that something like that should be expunged from your file just because you [moved],” Tokash said. “If I’m a commander and you’re coming to my unit, I don’t want to be flying blind that I have someone who sexually harassed someone in their previous unit. You’re a liability to me and, as a commander, I have a right to know that.”

Part of the independent commission’s report called for the military’s Catch a Serial Offender, which identifies repeat offenders of sexual assault, also include those who faced sexual harassment allegations.

When service members report a sexual assault, they can choose unrestricted or restricted reporting. The first initiates a criminal investigation while the latter does not. The Catch program allows those victims who choose restricted reporting to see if their perpetrator’s name appears in the system. The idea is that if a match appears, it could sway a victim to changing their reporting status and initiate an investigation.

“Serial sexual harassers can also be your serial sexual assaulters,” Lynn Rosenthal, chairwoman of the commission, said July 20 during a hearing about the report with the House Armed Services Committee’s subpanel on military personnel.

Khawam and Guillen’s sister Mayra Guillen attended the hearing. Khawam said they all hope to continue to work together to get these reforms passed to balance the criminal justice system of the military.

“We want to change a system that has loopholes and flaws to be a better system,” she said.