Asia-Pacific

In Okinawa, a push to revive a lost tattoo art for women, by women

The Washington Post July 25, 2022

Moeko Heshiki shows photos of her research and the hajichi tattoos she has done on other young women, mainly of Okinawan roots. (Michelle Ye Hee Lee/The Washington Post)

NAHA, Japan — Hana Morita was scrolling through Pinterest when she came across hajichi, a minimalistic tattoo worn by Okinawan women on their fingers and hands. Once common on the subtropical islands where traces of a distinct culture remain, the art had almost disappeared over a century of assimilation.

As a fourth-generation Japanese American who visited her grandmother in Okinawa every summer, Morita made researching hajichi part of her quest to understand her family's roots. Then, she found an Okinawan hajichi artist on Instagram and got her first tattoo.

"I wanted it to mark the physical affirmation of becoming more of myself," Morita, 22, said. "My grandma was really happy to see it, because her grandma also had hajichi."

Morita is among a growing number of women in their 20s and 30s who are discovering the lost art form through social media and driving a small but passionate comeback. They are part of a larger movement to preserve the uniqueness of Okinawa and show it is so much more than its reputation as a resort destination that hosts American military bases.

Okinawa was the independent Ryukyu kingdom before it was annexed by Japan in 1879 and then occupied by the United States for almost 30 years after World War II. This year marks the 50th anniversary of Okinawa's return to Japan from U.S. rule, but Okinawans say they are treated as second-class citizens in Japan despite shouldering the burden of the U.S. military presence.

Hajichi was banned in 1899 as the Japanese government pushed assimilation and as new norms about public decency emerged during the time when the country opened to foreigners after more than 200 years of isolationist policies. While tattoos are becoming more fashionable among younger Japanese, they remain stigmatized and often associated with the yakuza, the Japanese criminal syndicate.

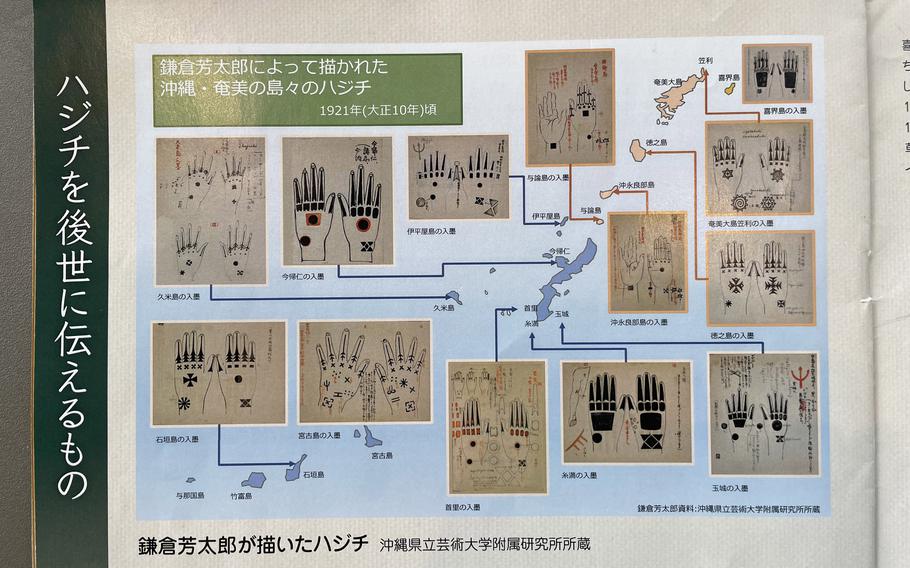

A map of the hajichi designs from various regions of Okinawa. (Michelle Ye Hee Lee/The Washington Post)

Now, attempts by a handful of tattoo artists in Okinawa and Tokyo to revive hajichi have reached artists and clients in diasporic communities in Brazil and Hawaii. Some view the resurgence as a callback to a time when Okinawan women held powerful positions as religious leaders and breadwinners. For them, it's a symbol of empowerment in a country that ranks among the lowest among developed nations on women's advancement.

"Hajichi is also a part of this idea that women possess power. And living in a patriarchal society like Japan, I think that's part of why I was drawn to hajichi," said Moeko Heshiki, 30, founder of the Hajichi Project. "Even in the tattoo industry, a lot of tattoo artists tend to be men. But hajichi was usually done by women for women, so this felt especially meaningful."

Growing up in Tochigi, north of Tokyo, Heshiki experienced microaggressions relating to her Okinawan identity. "You're light-skinned for an Okinawan," people would say and point out how her name doesn't sound like a typical Japanese name. (It's Okinawan.) But being Okinawan was important for her.

As she looked for a tattoo design that represented her family, she came across hajichi on Pinterest. She got her first hajichi from a tribal tattoo artist in Tokyo, then in 2020 opened her own studios in Tokyo and Okinawa. Tattoo artists in Okinawa now do hajichi, but Heshiki is the sole hajichi specialist — "hajicha" — on the islands.

Hajichi's origins are murky and date as far back as the 16th century, according to researchers.

It was a sign of pride of womanhood, beauty and protection from evil spirits. It could also indicate marriage. Young women often got hajichi through multiple sessions as a rite of passage through different stages of life, according to "Hajichi of Nakijin, A Vanishing Custom," a 1983 research paper. Islands in Ryukyu each had their own designs and customs.

Heshiki tries to stick to original techniques as closely as possible, hand-poking with bamboo needles and referencing designs in history books from secondhand bookstores and fabric from various regions.

She makes sure her clients are of Okinawan heritage before she gives them tattoos in the traditional locations of fingers, hands and wrists. Many are young, mixed-race women who find her on Instagram. For those drawn to it for aesthetic reasons, she tattoos them on different parts of the body to preserve the hand-worn tattoo for women of Okinawan descent.

The resurgence has led women to new discoveries about Okinawa before Japanese or U.S. rule. For example, when Heshiki showed her hajichi to her father, who was born in Okinawa under U.S. occupation, it triggered memories of his grandmother, who Heshiki learned also had the tattoo and spoke a different dialect that disappeared after the annexation.

And they hope to pass it down. Akemi Matsuzaki, a 32-year-old Okinawan native, teaches hip-hop dance and is often asked about her hajichi by her students, which leads to conversations about Okinawan Indigenous culture.

Moeko Heshiki shows photos of her research and the hajichi tattoos she has done on other young women, mainly of Okinawan roots. (Michelle Ye Hee Lee/The Washington Post)

Matsuzaki, whose grandfather is American, got her first hajichi this year and plans to complete a full design on both hands. When she turns 37, a milestone age in Okinawa, she plans on getting a special design to mark the year.

"When I got it done, it just felt so great and it just all felt so natural to me," she said. "Though I was born in Okinawa and am working here, getting hajichi made me feel even more strongly of the fact that I really am here, and I feel more comfortable and proud of who I am."

Still, hajichi is rare. Getting a tattoo, especially on an exposed body part like the hands, is a major commitment that could backfire professionally.

For those women, Minami Shimoji, a 30-year-old occupational therapist in Okinawa, offers an alternative: temporary hajichi using fruit-based ink that was used for Amazonian tribal tattoos. Shimoji learned about hajichi when she saw an elderly patient who had a marking on her hand that resembled the art.

Shimoji had grown up performing Okinawan dances and wanted to learn more. She aspires to be a full-time tattoo artist, but for now runs a studio part time out of an apartment building in Chatan, near a U.S. military base.

As military airplanes roared by, drowning out the music in her studio, she scrolled through the hundreds of comments on a TikTok video she made about hajichi.

She's aware of pushback from traditionalists who don't approve of her adaptation of hajichi into body art that lasts just two weeks. But even during the Ryukyu age, hajichi had evolved, she said.

"Hajichi originally had different designs depending on region or class, so it was never just this one form," she said. "I feel that culture is never static and it's something that is created together by people, and hajichi can evolve while respecting the traditional aspects."