Cpl. Kayla Noyles of the 16th Combat Aviation Brigade (right) poses for a photo at Grey Army Airfield, Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Wash., Jan. 10, 2022. Noyles recreated a historic photo of Lt. Col. Marcella A. Hayes Ng (left). Ng became the first black female to receive aviator wings in the U.S. armed forces in November 1979. (U.S. Army, 2022 photo by ShaTyra Reed)

An Army unit’s series of color re-creations of old black-and-white photos is a reminder of the battles Black soldiers have fought in war and in the fight for equality at home.

To mark Black History Month, the 16th Combat Aviation Brigade out of Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Wash., has been releasing one historic photo each week, alongside its modern re-creation.

The first two photos, shared side-by-side on Twitter, earned the praise of the Army’s top enlisted leader and others.

“Really well done,” Sgt. Maj. of the Army Michael Grinston said in a post that shared a photo of helicopter crew chief Cpl. Kayla Noyles of the 16th CAB mirroring an older photo of Lt. Col. Marcella A. Hayes Ng.

Some 42 years ago, then-2nd Lt. Hayes was the first Black woman in the U.S. military to receive aviator wings.

“People like Marcella Hayes inspire and motivate me to keep going because they make me realize the sky is the limit,” Noyles was quoted saying in a tweet.

Like Hayes, Noyles strives to be an example for “the next little girl or boy of color” to show that they are capable of overcoming whatever obstacles they may face in any profession, she said.

“Females are already scarce in Army aviation,” Noyles said. “Black females are a rarity.”

Four re-creations were shot by Staff Sgt. ShaTyra Reed, according to information in the Pentagon’s online repository of images and press materials.

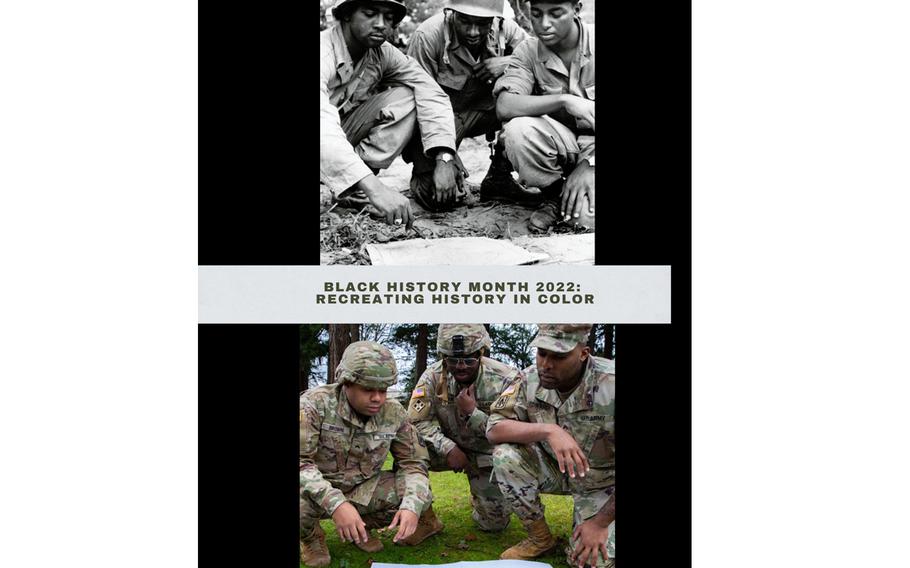

Sgt. Xavier Lewis, a wheeled vehicle mechanic, Sgt. Samuel Eseyin, a power-generation specialist, and Pfc. Nana Gyasi, a construction equipment repairer (left to right, in the color photo), of the 16th Combat Aviation Brigade, re-create a historic photo of Red Ball Express truck drivers Tech. Sgt. Serman Hughes, Tech. Sgt. Hudson Murphy, and Pfc. Zacariah Gibbs during World War II. (U.S. Army, modern photo by ShaTyra Reed)

But one set in particular, featuring soldiers of the 24th Infantry Regiment during the Korean War, hints at the troubled legacy of the Army’s treatment of its Black soldiers.

The modern version shows three noncommissioned officers posing like three first lieutenants with the 24th Infantry Regiment on Aug. 9, 1950, poring over a map.

While the Korean War was the first conflict in which desegregated American units took part, the segregated 24th Infantry Regiment, which was founded in the post-Civil War era, was at the center of several events that illustrated the harms discrimination wrought in America’s military.

In 1917, over 150 members of the regiment were involved in a deadly riot and mutiny that arose after a confrontation between white civilian police and Black military police in Houston.

One of the worst of World War I and the only race riot in U.S. history where more whites died than Blacks, it contributed to factors that led to the marginalization of Black units during both world wars, a 1996 Army review of the 24th Infantry Regiment’s performance in Korea found.

Cpl. Zavier Brown, an air defense battle management system operator, Sgt. Donell Gaiter, an aviation operations specialist, Sgt. Dustin Edwards, an air defense battle management system operator (left to right), of the 16th Combat Aviation Brigade, study a map at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Wash., Jan. 10, 2022, pose in a re-creation of a historical photo of of 1st Lt. Oliver Dillon, 1st Lt. Ernest Robinson, and 1st Lt. Walter Redd, all assigned to 24th Infantry Regiment during the Korean War on Aug. 9, 1950. (ShaTyra Reed/U.S. Army)

Until the Army took corrective action by upgrading several valor medals in the 1990s, no Black Americans were awarded the Medal of Honor in either war.

In Korea, the 24th Infantry Regiment’s Pfc. William Thompson became the first Black man to earn the nation’s highest valor medal since the Spanish-American War, just days before the 1950 photo highlighted in the 16th CAB series.

But the following month, Maj. Gen. William B. Kean would ask the Eighth Army to disband the regiment because it was “untrustworthy and incapable of carrying out missions expected of an infantry regiment.”

A controversy over the unit’s performance persisted for decades, until the Army ordered a study. Researchers found the unit’s performance had been hurt by many racial injustices that broke down trust and unit cohesion before and during its Korea deployment.

The regiment’s successes, despite those difficulties, “can only underscore the courage and determination of those among its members who chose to persevere and to do their duty in the face of adversity,” the study’s authors found.

The segregated regiment was inactivated in October 1951, by which time the Army had lifted restrictions on how many Blacks could be recruited. Commanders began putting them in whatever units needed them.

“Fears of hostility and tension between Blacks and whites proved unfounded, and performance improved in the integrated combat units,” said the study authors.

But despite attempts to root it out, racism and discrimination have persisted in the military for decades, The Associated Press found in a recent investigation.

And a recent study found that some 42% of active-duty troops of color rejected assignments to certain bases over concerns about racism at those locations.