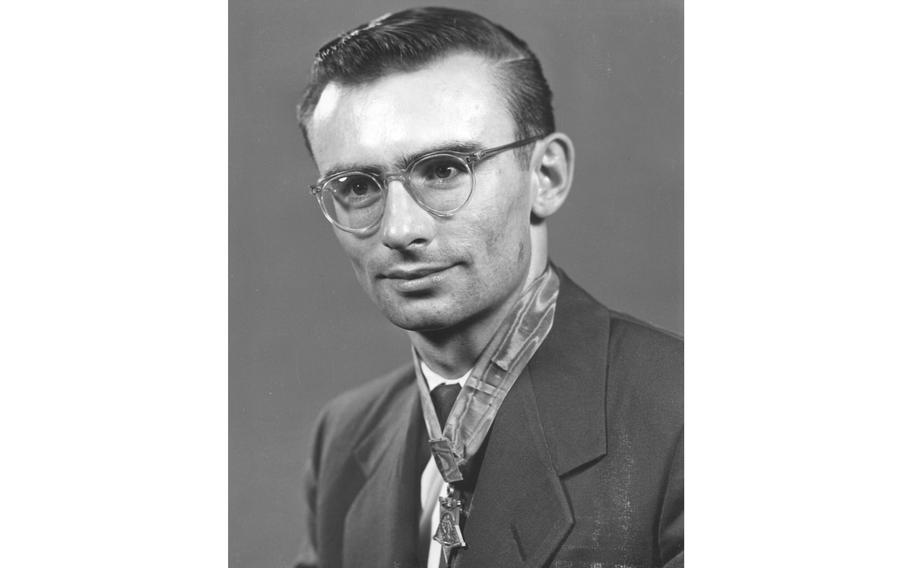

Marine Corps Pfc. Robert Simanek wears the Medal of Honor. (U.S. Marine Corps)

Before daybreak on Aug. 17, 1952, six Marines were pinned down on a Korean hilltop after an ambush. Forces from the Chinese-backed government in the north opened up with gunfire. Then came grenades.

One landed near Robert Simanek, a 22-year-old private first class in the Marine Corps. He managed to kick it away, but the blast injured his foot. A second grenade fell to his side.

“I couldn’t move too well. So I just sort of rolled over on top of that grenade,” he later recounted.

Simanek’s legs and hip took most of the blast and the grenade fragments, leaving the other Marines unharmed. The next year, he was presented with the Medal of Honor, the U.S. military’s highest decoration, citing his “daring initiative and great personal valor in the face of almost certain death.”

Over the decades, Simanek, who died Aug. 1 in Novi, Mich., at age 92, attended gatherings of Medal of Honor recipients, presidential inaugurations and events honoring veterans of the 1950-53 Korean War and other conflicts. He visited South Korea and was a guest at dinners hosted by Seoul officials.

There was one more honor awaiting. In December, construction began in San Diego on the future USS Robert E. Simanek, an expeditionary sea base vessel. “I didn’t think having a ship named after me would happen,” he told the Detroit News.

Robert Ernest Simanek was born April 26, 1930, in Detroit and worked in auto plants before he joined the Marine Corps in 1951.

In summer 1952, U.S.-led forces clashed with Chinese troops along a series of fronts known as the Korean War’s Battle of Bunker Hill, a pivotal but costly fight that gave allied units under U.N. command control of key front-line defenses.

Korean War Medal of Honor recipient and Detroit native Marine Corps Pfc. Robert E. Simanek, 85, is recognized by former Sen. Carl M. Levin, elected officials and distinguished guests during a naming ceremony at the GM Renaissance Center in Detroit in April 2016. (Kristine Volk/U.S. Navy)

Simanek was part of a predawn reconnaissance patrol about a week into the battle. The patrol was heading back to an outpost when the Marines were ambushed near Panmunjom, now in the demilitarized zone separating the two Koreas.

The Marine patrol splintered, Simanek recounted to the Lansing State Journal in 1954. He and five other Marines scrambled into a hilltop ditch to take cover. As radio operator for the patrol, Simanek was able to direct mortar and tank fire on the Chinese positions. But the attack on his group did not let up.

It took five hours to drive back the Chinese and allow help to arrive, he said. Simanek’s right side absorbed the brunt of the blast he smothered. “It put a good-size hole in my hip,” he later said. At the time, however, he didn’t know the extent of his injuries.

“I was really more concerned while I was sliding down the hill about the scrapes and cuts I was getting from the barbed wire and shell fragments on the ground,” he told the Lansing newspaper in 1954.

The battles for control of the area continued for weeks, with territory and redoubts often changing hands. In late August, warplanes under the U.N. command conducted the largest air raids of the Korean War in attempts to drive back the Chinese-led forces. In the end, Marines took strategic positions including Bunker Hill, also known as Hill 122, and held them throughout the war, which ended with an armistice but no formal peace treaty. The U.S. military has kept a presence in South Korea ever since.

Along the lines at Bunker Hill, the battlefield price was high with dozens of Marines killed or seriously wounded.

Simanek spent months under medical treatment on a hospital ship and in Japan before returning for more care in the United States. He walked with a limp for decades.

In October 1953, Simanek was presented with the Medal of Honor by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in a White House ceremony with six other recipients of the decoration, a five-pointed star attached to a blue ribbon.

Simanek’s other military honors include the Purple Heart. In an Armistice Day parade in November 1953 in Detroit, Simanek walked alongside Michigan’s governor, G. Mennen Williams, as more than 50,000 people looked on.

The Congressional Medal of Honor Society announced Simanek’s death but did not cite a cause. There are 65 living Medal of Honor recipients, the society said.

Simanek received a degree in business management from Wayne State University in Detroit and spent part his career in the auto industry and Small Business Administration.

His wife of 64 years, the former Nancy Middleton, died in 2020. Survivors include a daughter, Ann Clark of Traverse City, Mich.

On the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the Korean War, Simanek described the veterans of the Cold War conflict as a “quiet” cohort.

“We were the younger brothers and nephews of World War II, which was just over by five years,” he told the Lansing State Journal in 2000. “The Korean veteran was quite quiet because the nation and ourselves were in awe of the sacrifices of World War II veterans.”