The European robin has a protein in its retinas that is sensitive to Earths magnetic field, which helps guide its migration, Army-funded research has found. Researchers say the findings could one day help soldiers navigate without GPS. (U.S. ARMY)

U.S. military-funded research on how birds migrate in the winter could one day allow troops to navigate using the Earth’s magnetic fields.

The findings, announced last week, could result in a future device for use in battle, when GPS and other navigation tools are incapacitated.

Researchers analyzed the eyes of the European robin, a species that flies south from the U.K. and Russia to countries like Spain during the winter, an Army statement last week said.

They re-created the protein cryptochrome 4, which is present in the eyes of the robins. Scientists wanted to know whether the protein allows the birds to sense the Earth’s magnetic fields for navigation.

“The research shows that the magnetic field modifies the cryptochrome protein in a measurable way,” Stephanie McElhinny, of the Army Research Laboratory, told Stars and Stripes in an email.

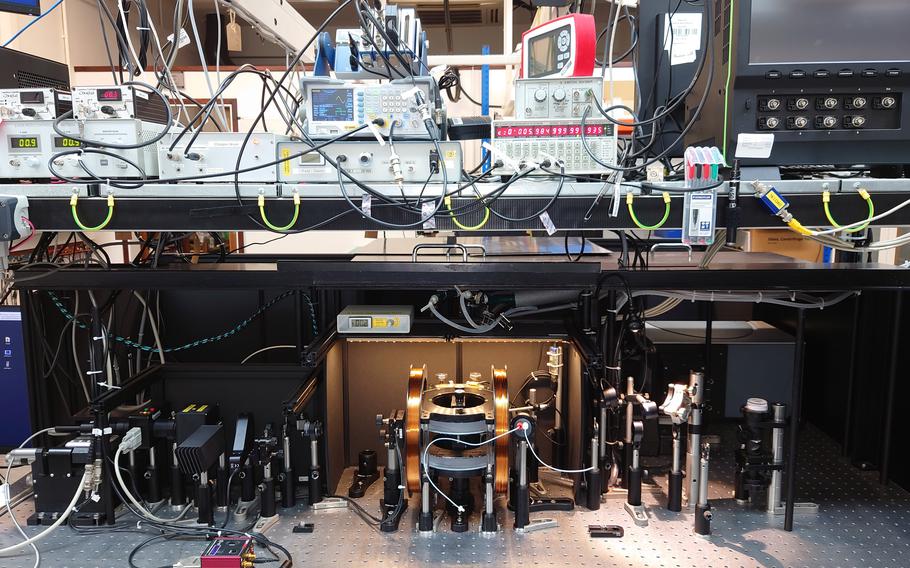

Scientists use equipment to measure whether a protein found in the European robin's eyes is sensitive to the Earth's magnetic field, in this undated photo. Army-funded researchers say the findings could one day help soldiers navigate without GPS. (Stuart Mackenzie/University of Oxford)

It’s likely that other proteins are also involved in helping birds navigate, and those still need to be discovered, McElhinny said. The magnetic fields used in the labs were also much stronger than normal.

Scientists at Oxford University and the University of Oldenburg in Germany conducted the research, which was published this summer in the journal Nature.

The research is in an early stage, but future troops may benefit as the military looks to find ways to navigate where GPS may not be an option.

Simulated war games conducted by the U.S. military, which is heavily reliant on networked communications and information from GPS satellites, have shown instances where its forces could be jammed and blinded early in a battle.

McElhinny envisions a future navigation device that uses cryptochrome proteins or a re-creation of them to measure the strength and direction of magnetic fields.

Troops could check this information against existing magnetic field maps.

“This research provides an interesting possible alternative technology for navigation that would only rely on the magnetic field of Earth,” McElhinny said.

Navigation based on magnetic fields would be more difficult to jam or spoof compared with the use of GPS satellite signals, she added.

Funding for the project came from U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command, the Army Research Laboratory, the Office of Naval Research Global and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.