U.S.

The science of heat domes and how drought and climate change make them worse

The Washington Post July 10, 2021

(The Washington Post)

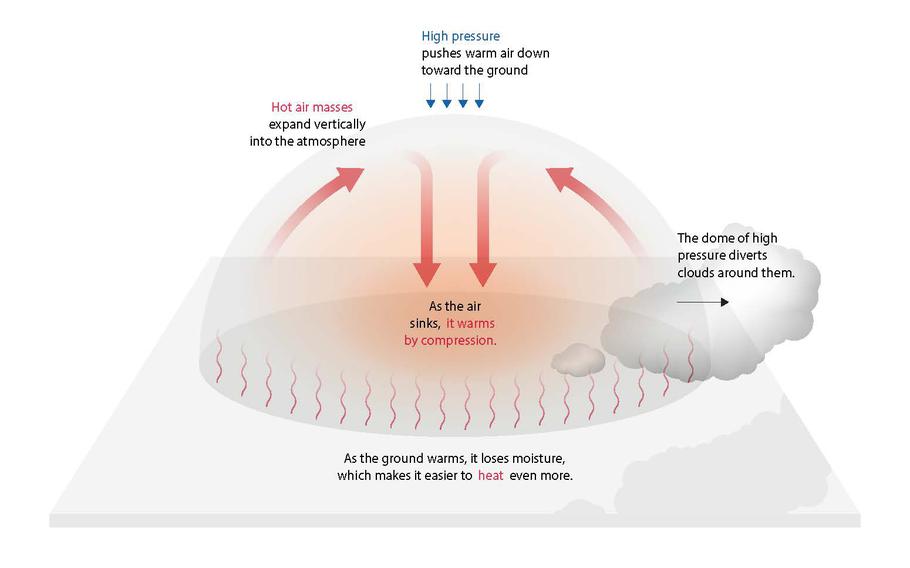

Record-breaking heat waves have roasted the Western United States several times already this summer. At the heart of these heat waves are “heat domes,” sprawling zones of strong high pressure, beneath which the air is compressed and heats up. They are a staple of summertime and the source of most heat waves.

Let’s explain how they work.

Hot air masses, born from the blazing summer sun, expand vertically into the atmosphere, creating a dome of high pressure that diverts weather systems around them.

As high-pressure systems become firmly established, subsiding air beneath them heats the atmosphere and dissipates cloud cover. The high summer sun angle combined with those cloudless skies then further heat the ground.

But amid drought conditions, the vicious feedback loop doesn’t end there. The combination of heat and a parched landscape can work to make a heat wave even more extreme. With very little moisture in soils, heat energy that would normally be used on evaporation — a cooling process — instead directly heats the air and the ground.

Jane Wilson Baldwin, a postdoctoral researcher at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University, said that given the severe drought in the West right now, many feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere are combining to make heat domes worse.

“When the land surface is drier, it can’t cool itself through evaporation, which makes the surface even hotter, which strengthens the blocking high [heat dome] further,” she said in an interview.

The situation is intensified by increasing background temperatures due to the burning of fossil fuels.

“You would be hard-pressed to come up with a metric of heat waves that isn’t getting worse under global warming,” she said, adding that the increasing intensity and duration of heat waves is particularly clear.

One way to gauge the magnitude of a heat dome is to measure the height of the typical halfway point of the lower atmosphere — at the 500 millibar pressure level. The higher this pressure level is, the hotter it is, because hot air is less dense than cold air and expands the atmosphere vertically.

For this pressure level to stretch to heights of 600 dekameters, or 19,685 feet, is quite rare, but several of the heat domes this summer and in recent summers have come close to or eclipsed that threshold.

Evidence suggests climate change is increasing the frequency of heat domes this intense, pumping them up higher into the atmosphere, not unlike adding more air to a hot-air balloon.

The Washington Post’s Matthew Cappucci contributed to this report.