U.S.

In Va. governor’s race, raging debate about schools takes center stage

The Washington Post July 3, 2021

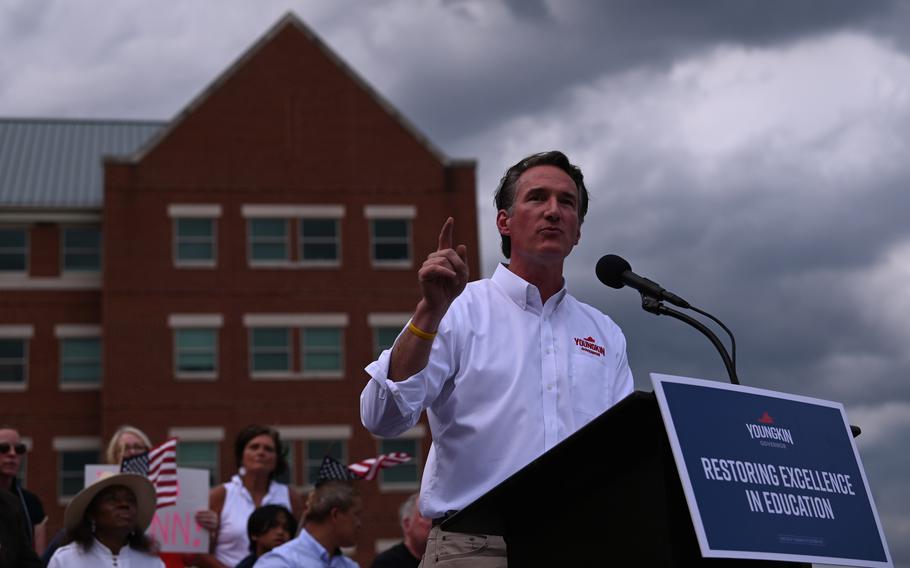

Virginia Republican gubernatorial nominee Glenn Youngkin speaks about critical race theory in Loudoun County schools on June 30, 2021, in Ashburn, Va. (Michael Blackshire/Washington Post)

RICHMOND, Va. - Parents and teachers already exercised about public schools amid raging K-12 culture wars and the aftermath of pandemic-era shutdowns are proving attractive targets this year for Virginia gubernatorial candidates - in strikingly different ways.

Democrat Terry McAuliffe, a former governor attempting a comeback, launched his campaign in December in front of a Richmond elementary school then-shuttered by the pandemic.

He released a detailed plan that day to invest a record $2 billion a year to raise teacher pay above the national average, get every student online, expand preschool to 3- and 4-year-olds in need and eliminate racial disparities in education. He has broadened his pitch since then, churning out position papers on 14 other issues, although his schools plan still gets top billing on his campaign website.

Republican Glenn Youngkin, while far lighter on details, has leaned heavily into cultural issues consuming some school boards, especially in vote-rich Northern Virginia. He has vowed to ban critical race theory, an intellectual movement that examines the way policies and laws perpetuate systemic racism; opposed certain transgender rights policies; and accused the state - falsely, education officials say - of planning to eliminate accelerated math, the Pledge of Allegiance and Independence Day from school curriculums.

While schools are a classic kitchen-table issue that candidates typically nod to, it has been a long time since K-12 education has played such a prominent role in a Virginia governor's race, political analysts and observers say. Republican George Allen, who was governor from 1994 to 1998, is remembered for ushering in standardized testing as an accountability tool - but even for him, the marquee campaign theme was law and order.

The pandemic put schools squarely on the front burner this election cycle, both with the upheavals caused by closures and the scrutiny that virtual learning brought to classrooms. Parents working from home suddenly had front-row seats to their children's education - and some did not like what they saw.

"Parents have had to think more about education over the past year than ever before, because they were seeing a lot of it in their own houses," said Stephen Farnsworth, a University of Mary Washington political science professor and the director of the school's Center for Leadership and Media Studies.

Farnsworth says it makes sense that McAuliffe would offer practical, nuts-and-bolts plans for schools as just one part of an expansive set of policy goals, while Youngkin would zero in on a more limited set of highly animating issues.

"McAuliffe doesn't need to hit the long ball to win. A series of issues that get him on base - improve teacher salaries, improve broadband access, additional resources . . . [for] schools recovering from covid education troubles - these are effective," he said. "Republicans, given the bluish tint of the Virginia electorate, have to swing for the long ball."

As a former governor, McAuliffe has a background on education that he can point to, such as a record $1 billion investment in K-12 schools, as well as plans for a second term. His schools policy - laid out in a six-page document studded with footnotes to meaty educational research - ranges from lofty promises to address "modern-day segregation in schools" to in-the-weeds plans to train and retain more teachers.

All of that appeals to Pam Davis-Vaught, principal of Highland View Elementary School in Bristol, on the border with Tennessee. Hers is a poor school, where teachers have chipped in to buy washing machines for use on campus to ensure children have clean clothes. It benefited from nutrition programs expanded under then-first lady Dorothy McAuliffe, but issues remain at a run-down schoolhouse dating to the 1930s.

"When we shut down for covid on March the 13th, the rats and things from the neighborhood kind of moved in, and it took us quite a bit to exterminate them," said Davis-Vaught, a coal miner's daughter who also has worked closely with the region's Republican legislators. "That makes learning very difficult, when your teacher is constantly on the lookout for something."

She thinks McAuliffe has the right idea, not only with his promised infrastructure investments, but also with his plans to provide broadband and create virtual internships for students in areas such as hers, where job prospects are limited.

"He's going to be our champion," she said. "He's going to do as much as he possibly can for school infrastructure, small and rural schools, economically disadvantaged children."

Youngkin's approach has also won him fans.

"Who wants a leader who will stop this critical race theory garbage?" Rooz Dadabhoy asked to cheers recently, as she introduced Youngkin and the rest of the GOP's statewide ticket at an event that drew more than 300 women to a country club in the Richmond suburb of Glen Allen.

In the crowd was Julee Spitzer, a 49-year-old stay-at-home mom who lives in Richmond's West End and thinks critical race theory is creeping into her teenage daughter's curriculum.

"It's been a slow-growing cancer," she said. "It started out years ago, with a focus on sexism. And now it's turned to - it's just such a focus on race. My children weren't raised that way. I wasn't raised that way. We have friends of every religion, creed. They're well-traveled. They just don't view the world through that lens. And I think it is so unfortunate, and sad, and so divisive for anybody to put that lens in front of them."

Critical race theory, or CRT, is a once-obscure academic theory that looks at racism not as individual acts, but as a systemic phenomenon baked into the structure of society.

"Defining it might be like nailing Jell-O to a wall, but this is a familiar type of argument," said Kyle D. Kondik, who analyzes elections at the University of Virginia's Center for Politics. "It's a different version of the same argument that cultural conservatives have made for years, that higher education . . . [is ] too liberal, they're indoctrinating students with left-wing ideas, they're too critical of the history of the country."

Schools across the state were still closed down early this year, when both parties' gubernatorial nominating contests were heating up. Youngkin and some of his rivals for the Republican nomination made those closures central to their campaigns, blaming Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam for the prolonged shutdown. (Northam, like all Virginia governors, is banned by the state constitution from seeking back-to-back terms.)

But as schools began reopening in late winter to in-person instruction, that issue started losing salience. Cultural battles in education rose up as replacements - nowhere more fervently than in Fairfax and Loudoun counties.

In Fairfax, much of the controversy has centered on elite magnet school Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, or TJ, which has for decades admitted very low percentages of Black and Hispanic students. Following the murder of George Floyd last year by a police officer in Minneapolis and subsequent protests against racial injustice, Superintendent Scott Brabrand enacted radical changes to TJ's admissions meant to boost the school's diversity.

The changes - eliminating an admissions test and considering applicants' socioeconomic backgrounds - led to the most diverse class of admitted freshmen in recent school history, but sharply reduced the number of Asians, a group the GOP has been trying to woo. The move sparked a fierce backlash, including two lawsuits.

In Loudoun, the battles emerged over CRT and transgender rights. Parents have seized on the school district's equity work, launched in response to two high-profile reports that found widespread racism was imperiling Black and Hispanic students' progress, to argue that schools are trying to teach White children to feel ashamed of themselves, because their race means they have historically been part of an oppressive system.

Separately, Loudoun's attempt to implement a 2020 state law requiring school systems statewide to treat transgender students according to their gender identities, in part by granting these children access to gender-specific restrooms and sports programs, has generated national headlines and at least one lawsuit.

Youngkin has seen an opening in all of that. He has opposed transgender girls' participation in girls' sports and has championed the cause of a teacher who was recently suspended - and later reinstated by a judge - for saying he would not address transgender students by the pronouns they use. Youngkin has warned that CRT undermines Martin Luther King Jr.'s goal of racial harmony by reducing people to their racial identities.

For that message to work in solidly blue Northern Virginia, though, Youngkin will have to find a way to talk about what he sees as "progressive excesses in schools" in a way that "doesn't sound like Dick Black," U-Va.'s Kondik said, referring to the retired Republican state senator who was one of the legislature's most vocal conservatives.

Youngkin sounded less like fiery Black and more like relatively moderate former president George W. Bush at a rally Wednesday outside Loudoun schools headquarters. Youngkin echoed Bush's rhetoric and affinity for standardized tests, saying "the soft bigotry of low expectations" had led McAuliffe to scrap some of those Allen-era tests.

"I often say that Terry McAuliffe believes in every child being left behind," he said. Youngkin did not mention that Virginia Republicans had led the charge to eliminate some of the tests, agreeing with McAuliffe that testing was excessive and led instructors to teach to the test. Votes to scrap some tests in 2014 passed unanimously in the GOP-dominated House and the narrowly divided state Senate.

The testing issue was a new line of attack from Youngkin and it figured into his announcement at the Loudoun rally of a broader but still-nascent educational agenda. Youngkin said he would sign an executive order to return Virginia schools to "pre-McAuliffe standards" related to standardized tests and school accreditation.

That, and banning CRT, would be the first of a three-phase plan he said he would roll out "in the coming weeks." He said the second phase would involve raising teacher pay and investing in facilities. The third would be "a mission for school choice like Virginia has never seen."

Youngkin has not fleshed out any of those plans on his campaign website, which still lacks the typical "issues" page, but his campaign provided a three-page summary of the first phase. Still drawn in broad strokes, it sets some specific policy goals, such as creating more magnet schools like TJ in a variety of subject areas and ensuring that every child can read, write and understand basic math by the third grade.

It has footnotes of its own, including to a Washington Post editorial linking the lowered school standards to "significant drops" in national reading scores for fourth- and eighth-grade Virginia students.

In the crowd at Youngkin's Glen Allen rally was Angela Allen. The school board candidate is running on a platform that includes banning CRT, which she said was "permeating our classrooms." She said she has seen it in her daughter's AP English class.

"They had to read content from a New York Times opinion columnist about the struggles of being a Black man in New York City," she said in an interview after the rally. "I had no problem with reading a diverse range of materials. The problem was then the assignment was . . . to write about how they could identify with that man's situation. Well I'm not sure how effective that is or what the endgame was for that. My daughter, being at that time a 16-year-old White girl in Goochland County, she neither could relate to his circumstances nor speak to it intelligently."

Allen also objected to a lesson that she said involved "attacking images of Barbie, and how Barbie represents what suppresses all other women, and how you have to look like Barbie to get ahead." She said the lesson was problematic for her daughter, who, like the doll, has long, blond hair.

Youngkin gave a shout-out to Allen before launching into his speech. He had already recognized a few state legislators in the crowd, as well as former governor Jim Gilmore and Gilmore's wife, Roxane. But the biggest cheer went up after his nod to the school board candidate - little known outside her county, but a figure on the CRT front lines.

"Is there anybody in this room that thinks school boards don't matter?" Youngkin asked rhetorically. "They matter big time."