Fishing village on a sunset background in Kaliningrad, Russia. (iStock)

VILNIUS, Lithuania — Train passengers traveling between Moscow and Kaliningrad, Russia’s militarized exclave, are confronted with the carnage Russia is inflicting on Ukraine every time they pass through this nation’s capital.

There, on both sides of the track on platform No. 5 of Vilnius’ central railway station, they are prompted to look at 24 large graphic photos from Russia’s war against its smaller neighbor.

“Today Putin is killing peaceful civilians in Ukraine,” the writing on the photos reads. “Do you agree with this?”

On a recent morning, a few passengers headed to Kaliningrad from Moscow looked out toward the display as the train paused for a 30-minute “technical stop.” One woman closed the curtains on her window.

From Vilnius, the train will pass through the so-called “Suwałki Gap” between Kaliningrad and Belarus, a 60-mile-long strip of land along the Lithuania-Poland border that has long inspired fear in the Baltics and among NATO’s planners.

Belarus hosted war games near the area in August, offering an alarming reminder to some military strategists of how a revanchist Russia could partner with Belarus to cut off the three Baltic nations once under Moscow’s rule — Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania — from the rest of NATO.

Train passengers traveling between Moscow and Kaliningrad pass through the central railway station in Vilnius, Lithuania, where they are greeted with a display of graphic photos from Russia’s war in Ukraine. The photo reads: “Today Putin is killing peaceful civilians in Ukraine. Do you agree with this?” (Svetlana Shkolnikova/Stars and Stripes)

But for now, the only connection between Russia’s pliant ally and Russia’s outpost on the Baltic Sea are train tracks carrying both Russian people and goods through European Union and NATO territory.

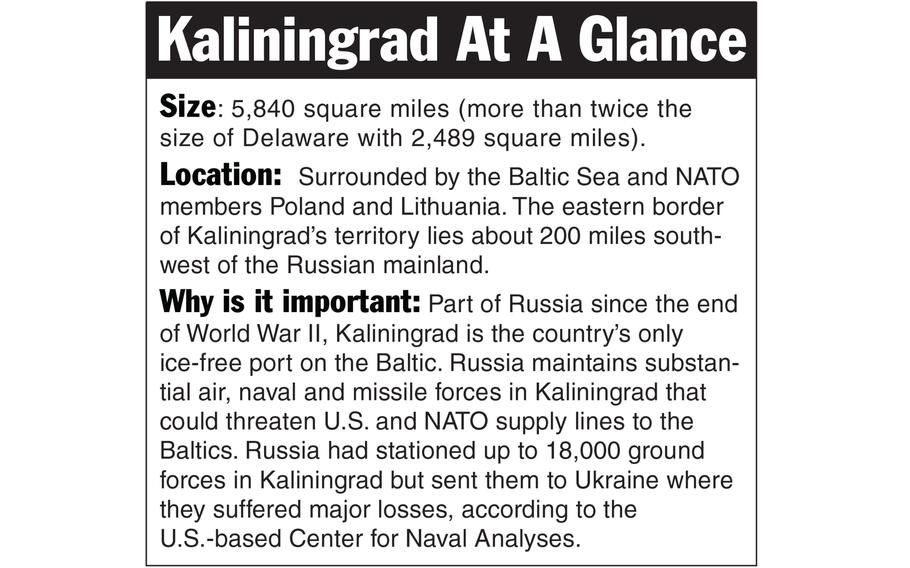

Kaliningrad, a former part of Germany that was taken by the Soviet Union as a spoil of World War II, finds itself increasingly isolated amid Russia’s war in Ukraine as neighboring countries restrict its residents’ movement, NATO adds members, and the Kremlin focuses its attention on waging war.

“Those who live in Kaliningrad have always felt like they’re on an island and now it’s an even bigger feeling,” said Alexei Chabounine, a 53-year-old journalist with the Kaliningrad-based news site “Russian West.” “There is a general feeling of being locked in.”

Britain’s defense ministry reported last month that Russia likely moved strategic air defenses from Kaliningrad to backfill recent losses on the Ukraine front, demonstrating the “overstretch” the war has caused for Russian capabilities.

Still, Kaliningrad remains a source of power projection for the Kremlin into NATO’s northern flank and one of the most militarized places in Russia, home to the Baltic Fleet as well as nuclear-capable Iskander missiles and other powerful armaments.

The Ukraine war has left a mark on Kaliningrad, Chabounine said. About 5,000 of the region’s population of 1 million have been mobilized to fight in Ukraine, and estimates by locals put the death toll at around 450 people. Their graves occupy not just military cemeteries, but civilian ones, too.

The exclave’s authorities seldom speak about the dead, but they do talk about how Kaliningrad is helping the war effort, Chabounine said. The region is providing quadcopters, camouflage nets and clothes and allocating a significant portion of its 2024 budget to help finance the war. Soldiers who signed contracts with the army will be paid an additional 100,000 rubles, or about $1,111, he said.

(Noga Ami-rav/Stars and Stripes)

When asked if the people of Kaliningrad support the war, Chabounine said he could not answer without violating Russia’s war-time censorship laws.

“People try to avoid the topic of the special military operation, they try to live like before,” he said, using the Kremlin’s approved language for its invasion of Ukraine. “People try to hold on and live a regular life.”

Russia is pouring money into Kaliningrad to help blunt the impact of Western sanctions, and investment in the exclave’s vast military infrastructure continues, Chabounine said. But there is no construction of fortifications or preparations for an expanded war that would bring Russia into conflict with NATO.

“Even if Russia attacks the Baltics, there will be nothing left of Kaliningrad. There’s no way to defend it — we’ll be blockaded,” he said. “The authorities say they will defend us, but truth be told, I don’t see that happening.”

The threat from Kaliningrad has receded with Russia mired in Ukraine and NATO welcoming Finland, and likely Sweden, into its ranks, experts say. Russia’s goal of turning Kaliningrad into a launching pad to dominate the Baltics has “effectively been canceled,” according to a November report published by the French Institute of International Relations.

“With the accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO, the Baltic theater is reconfigured so profoundly to Russia’s disadvantage that no amount of effort could make ‘Fortress Kaliningrad’ defensible,” the report states.

Eerik Purgel, head of the border and migration control service in Estonia’s northeastern region bordering Russia, said Estonia is thrilled to see “brother” nation Finland in the military alliance and is eagerly awaiting the accession of Sweden.

“The Baltic Sea will become the NATO Sea,” he said.

Russia has long been preparing for the eventuality of Kaliningrad getting cut off from the Russian mainland, said Tomas Jermalavičius, head of studies at the Estonia-based International Centre for Defence and Security think tank.

Moscow in recent years has tested Kaliningrad’s capacity to operate its own power grid and installed a floating gas terminal to lessen Kaliningrad’s dependence on pipelines that run through Lithuania, he said. The terminal has enough storage space to supply Kaliningrad for a month, according to Chabounine.

“Obviously they have a sense that this might become a very isolated part of Russia in a major crisis,” Jermalavičius said.

(Noga Ami-rav/Stars and Stripes)

The Kaliningrad exclave, located more than 200 miles from mainland Russia, has always stood a bit apart from the rest of the country, said Sergey Sukhankin, a Kaliningrad native and senior fellow at the Jamestown Foundation, a defense think tank.

It was populated by a mix of people from across the Soviet Union after World War II, and its residents prided themselves on being “not entirely Russian” and a part of “Russia’s Europe,” he said. Cross-border travel, especially to neighboring Poland, became frequent after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

But ties to Europe began to fray with Russia’s first incursion into Ukraine in 2014. Authorities in Kaliningrad cracked down on German and Lithuanian cultural institutions, seeking to erase traces of the exclave’s pre-Soviet past. Last summer, after a transit dispute with Lithuania, a Kaliningrad court shut down the Lithuanian Language Teachers’ Association, a prominent Lithuanian group in the region.

“Today, if you ask the locals, the majority would say that the West poses an existential threat to Kaliningrad,” Sukhankin said. “How they think is very much in line with the rhetoric that is promoted by the Kremlin.”

Not everyone agrees with that characterization. Polish politician Radosław Sikorski last year advocated for the easing of travel limitations on the residents of Kaliningrad, calling the exclave’s residents the most “Putin-skeptic in Russia.”

“Baltic Russians are a hope for their country’s future,” he wrote on X, formerly Twitter.

For years, there has been agitation among some fringe elements in Kaliningrad to form an autonomous Baltic Republic and possibly secede from Russia. The Baltic Republican Party was founded explicitly for that purpose in 1993 before being dissolved by Russia in 2003.

One of its members, Rustam Vasiliev, continues to champion the group’s cause, even after immigrating from Kaliningrad to the United States nearly a decade ago. He envisions Kaliningrad as a Europe-leaning republic with Königsberg, the city’s former German name, as its capital.

Perhaps fallout from the Ukraine war could set the stage for such a split, he said.

“The region is like a heavy suitcase without a handle for the Kremlin,” Vasiliev said. “It is inconvenient to carry, but the Kremlin is too greedy to drop it and walk away. What will be in the future only God knows.”

People gather to watch a festive parade marking the 750th anniversary of Kaliningrad, Russia’s westernmost city, on July 1, 2005. (Sergey Ponomarev/AP)