Asia-Pacific

AnalysisChina wants to mend ties with the US, but it won't make the first move

The Washington Post November 13, 2022

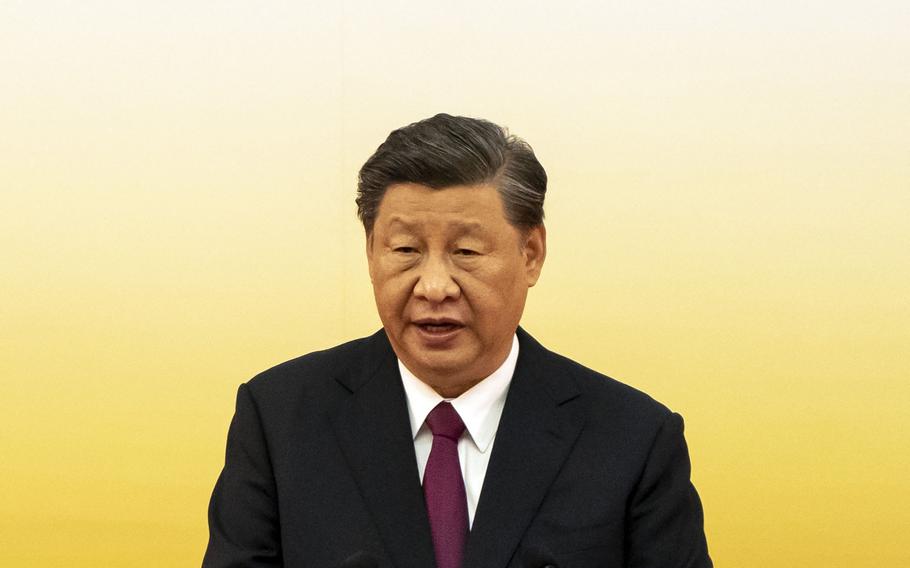

Xi Jinping, China's president, speaks at a swearing-in ceremony for Hong Kong's chief executive John Lee in Hong Kong on July 1. (Justin Chin/Bloomberg)

An American policy wonk in China rarely receives the attention paid last month to Scott Kennedy, the first U.S. scholar to visit since Beijing's strict coronavirus travel restrictions began over two years ago.

For Kennedy, an expert on Chinese business and economy at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank, it was intended as an icebreaker trip. But the tenor of his meetings with more than 100 academics, businesses and officials, including Vice Foreign Minister Xie Feng, surprised him.

Their interest in dialogue was in part to make clear the country's apprehension over its strained relationship with the United States. "There is significant concern in Beijing about U.S. motives. They see Washington as having a deep-seated fear of any rivals," Kennedy said after returning home. "From their perspective, the ball is in the U.S. court."

President Joe Biden intends to use his Monday meeting with Chinese leader Xi Jinping at the Group of 20 summit in Bali to establish a "floor" for the relationship. China, too, has signaled it wants to put ties back on track after several years of fierce disagreements over trade, technology and human rights. But for Beijing, doing so is not about agreeing to disagree or working out how to avoid the worst-case scenario of outright conflict.

Since being reconfirmed as paramount leader last month, Xi is more focused than ever on China becoming a modern socialist superpower with global influence — a status he expects the United States to accept. Chinese experts say that fixing the relationship will require more than a show of goodwill from the United States. It will take agreement on fundamental aspects of the relationship, including the fate of Taiwan, the self-governed, democratic island of 23 million that Beijing claims as part of its territory.

"The United States thinks that so long as there is no conflict or crisis in relations, then that's fine. But China wants to see evidence of progress, especially when it comes to Taiwan," said Wu Xinbo, dean of International Studies at Fudan University in Shanghai.

Yet Xi's determination to take control of the island, by force if necessary, has only grown in response to American efforts to shore up Taiwanese defenses in the wake of Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

After back-to-back pandemic years of minimal in-person contact, with many government channels canceled, suspended or lapsed, unofficial dialogues have been among the few tools left to keep the two sides from continuing to talk past each other. Well-known Chinese scholars have begun traveling to the United States in recent months, and they have invited American counterparts to do the same in reverse.

"If we can revive communication mechanisms, then in the future we won't have to overly rely on top leaders meeting," Wu noted.

That state media hailed this uptick in exchanges as a sign of easing tensions reveals just how bad things are. Sixteen months ago, Foreign Minister Wang Yi presented lists of complaints and demands to U.S. diplomats in Tianjin. China made clear the United States would need to make the first move, and it had three bottom-line requirements: no attempts to undermine China's development, no challenges to its political system and no "harm" to its sovereignty claims on Taiwan, Hong Kong and the South China Sea.

Beijing's position hasn't changed since then. What has changed, however, is Xi's degree of control at home and concern about the state of the world. At the recently concluded 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, where his rule was extended for at least another five years, Xi stacked the top leadership with loyal lieutenants and warned of "dangerous storms" undermining China's rise.

Some in China argue that Biden is too constrained domestically to make lasting agreements or truly improve ties.

"Beijing thinks that White House control over the Taiwan issue is decreasing, because Congress has grabbed the wheel," said Zhao Minghao, a professor at the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University in Shanghai. "Biden faces a divided government after the midterms, which has escalated the risks of China and the U.S. falling into open hostilities over Taiwan."

Chinese leaders are especially concerned about Biden's efforts to rally allies. In a response to Secretary of State Antony Blinken's speech on China policy in May — in which he called the country "the most serious long-term challenge to the international order" — the Ministry of Foreign Affairs accused the United States of attempting to create an Asian-Pacific version of NATO with Australia, Japan and Korea to "disrupt security and stability" in the region.

Though the relationship began deteriorating during the Trump administration, Zheng Yongnian, an influential scholar at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, said its decline has become more substantive under Biden. The president has "weaponized and politicized" trade rather than merely try to slow China's economic and technology development, Zheng said.

When Biden first took office, China signaled a degree of willingness to work with the United States on areas of shared interest while both tried to minimize differences. But the approach has largely failed, with Beijing suspending or canceling military-to-military talks, anti-narcotics cooperation and climate change discussions in retribution for House Speaker Nancy Pelosi's visit to Taiwan in August.

"On the U.S. side, it's all about crisis communications. How do we prevent a worst-case scenario? Whereas on the Chinese side, the way to responsibly manage the competition is to reach an agreement on basic principles," said Rorry Daniels, managing director of the Asia Society Policy Institute in New York.

Some Chinese scholars, Daniels added, had even raised the idea of trying to produce a joint communique such as the three foundational documents that shaped the nations' dealings with each other in the 1970s and 1980s.

"China is really probing for a north star to point to and say 'This is the nature of the relationship,'" she said. "But the U.S. isn't approaching China with the same mind-set."

A report released in May by Renmin University of China offered three possibilities for future ties between the countries. The best case was simmering tension and fierce competition. The middle scenario was technological, economic and cultural decoupling.

The last was all-out nuclear war.