Asia-Pacific

After a daring bridge protest in China, symbolic protests spread globally

The Washington Post November 10, 2022

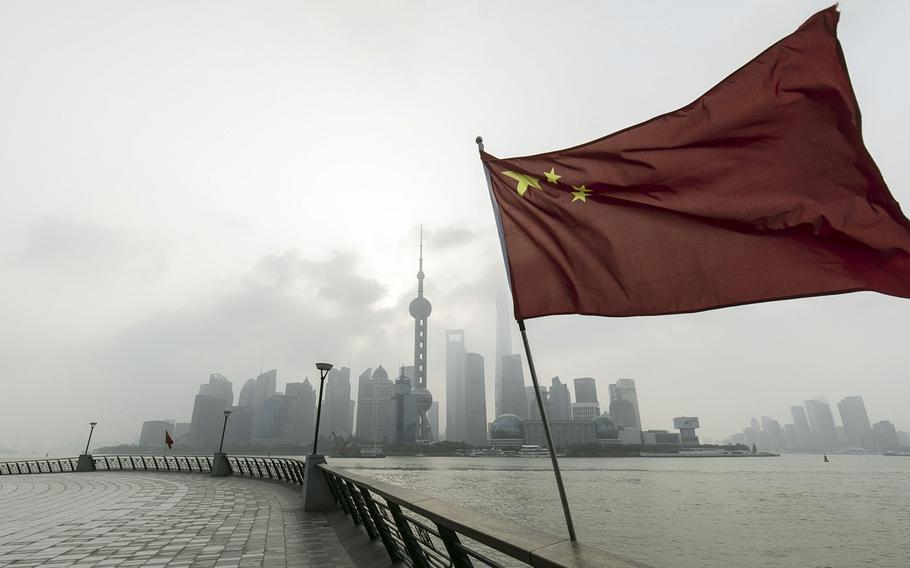

A Chinese flag in front of buildings in Pudong’s Lujiazui Financial District in Shanghai on Oct. 17, 2022. (Qilai Shen/Bloomberg)

Authorities moved fast when a daring lone demonstrator disguised as a construction worker draped two white banners over a busy Beijing overpass in October, their message calling for the ouster of Chinese leader Xi Jinping just days before he would secure a historic third term.

The protester was immediately detained and the banners pulled down. Mentions of the incident, including social media posts with the word "bridge" or "Beijing," vanished within a few hours. Tweets by a 48-year-old scientist named Peng Lifa and messages he left on ResearchGate — all almost identical to the banner's slogans — were deleted.

But it was already too late. By the next day, posters bearing the same slogans appeared at universities in the United States and Canada. Copycat demonstrations have since spread to more than 350 campuses around the world, organized by Chinese students who are tired of seeing their country move backward. And Peng, although never confirmed as the Sitong instigator, is now known as "Bridge Man" — an echo back to the unknown man who faced down a column of Chinese military tanks leaving Beijing's Tiananmen Square a day after the 1989 massacre there.

In many cases, the students are protesting for the first time. This nascent political awakening has surprised both human rights advocates and the demonstrators themselves. It builds on protest movements that came before, from the pro-democracy student rallies in Tiananmen to the #MeToo pushback in China during the 2010s and the anti-extradition demonstrations in Hong Kong in 2019.

One 23-year-old woman had just arrived in London for a graduate program when she saw news about the Sitong Bridge banners. Prompted by Instagram posts showing signs hung by students in the United States, she printed fliers late at night and put them up around her school. It was the first time she had engaged in any form of political expression. By the next week, she was attending her first demonstration, a rally outside the Chinese Embassy.

"I had no idea what it would be like, and I had no experience at all," said Wu, who did not give her full name out of safety concerns. When she got to the embassy, just blocks from Regent's Park, she found some 10 mainland Chinese students standing around. Nobody quite knew what to do.

One person suggested they begin shouting the Sitong Bridge slogans, "Life, not zero-COVID policy; freedom not lockdown; elections not dictatorship." But others worried the group wasn't big enough to get passersby to take notice. Finally, they found their voice.

"At first, I felt a bit nervous to speak up, but by the second and third time around, I was really shouting the slogans," Wu said. She soon was in tears. "Even though there weren't many people, when you shout out loud, you can feel the courage between everyone, and it makes you less afraid."

Initially, the copycat protests consisted of individual students furtively leaving posters with those slogans on their campuses or airdropping fliers to strangers in public places — what activists called a "poster movement." In recent weeks, these isolated actions have begun to coalesce as supporters meet and organize actual events through Telegram groups. Demonstrations have been held in London, Toronto, Los Angeles, Sydney and New York; another in Berlin is set for Saturday.

For many participants, it has almost been "like a 'political coming out' experience," explained moderators of Citizens Daily CN, an Instagram account run by Chinese activists collecting images of Sitong-inspired protests from myriad countries.

Such mobilization is remarkable given the years-long crackdown on all forms of Chinese activism both within and outside of the country. Under heavy social controls and censorship, even the largest waves of public outcry in China tend to peter out after time. Citizens overseas also come under state pressure if they take part in activities seen as critical of the ruling Chinese Communist Party.

"It's very similar to our generation when we went to Tiananmen Square, at first very cautiously, and then you realize you are not alone," said Fengsuo Zhou, a former leader of those long-ago protests who now lives in the United States.

The demonstrations reveal the frustration and pessimism of young Chinese as they look at the nation's continued COVID restrictions, its slowing economy and their shrinking job prospects. Many are rattled by the ever-more-controlling government under Xi.

Joe Zhang, a 23-year-old student from Zhengzhou, is in Berlin helping to organize this weekend's event. He left China in 2019 after reading about its crackdown on Uyghurs in Xinjiang, which brought back what he had seen firsthand while traveling in a neighboring region with another Muslim minority under heavy policing.

His point of reference was "1984," George Orwell's dystopian novel. "I was terrified," he said. "I never realized that I was living in the book."

Overseas activists are trying to build on the momentum. Chinese artist Jiang Shengda, based in France, published a draft manual for Chinese protests abroad with tips. It also solicits advice from Hong Kong and Uyghur activists.

Mainland students are taking inspiration from overseas Hong Kong demonstrators who continue to rally against Beijing's increasing control over the city. On Oct. 23, protesters from both China and Hong Kong converged outside the Chinese Embassy in London, with the Hong Kong students cheering on their counterparts from the mainland.

One young mainland woman said she felt safer with the Hong Kong protesters around. As she got closer to the embassy gate, they told her to protect her identity and not to allow anyone to take photos or video of her. "I learned from them how to negotiate with local governments and the police, how to organize a crowd, how to make protest posters," she said, speaking on the condition of anonymity because of concerns for her security.

The Chinese protesters are also building on approaches honed on the mainland under tight censorship, including what's known as a jieli, or "pass on the baton," a collective protest where internet users overwhelm censors with various iterations of the banned content. The strategy was used in China after the death of whistleblower doctor Li Wenliang in 2020 and later during the widely criticized Shanghai lockdown.

"Chinese people around the world joined this protest spontaneously, with no leader or organization," said one Chinese law student in Amsterdam, applauding it as a way to resist. "I have seen how the government disguises the truth, ignores people and uses their power to control everything."

Yet any Chinese student overseas runs a risk in demonstrating, knowing their compatriots could report them to Chinese authorities or expose them online.

Lam, who is from Shanxi province and now studying in Sydney, detailed how posters she put in public places at her university have been torn down. One she left on a restroom wall read, "You cannot tear down an idea. Ideas are bulletproof." Someone scrawled a response in Chinese: "Yes, but I can tear off your mouth."

"Now that I have met people who share my thoughts, I feel much better. I know I'm not the only one," Lam said, disclosing only her surname out of safety concerns. "I'll just keep posting more posters."

The Sitong Bridge protest has inspired activism even within China. The banners' slogans have sprung up in bathroom stalls — one of few public spaces without surveillance cameras.

In October, one man in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong used a label maker to make stickers calling on citizens to "depose Xi Jinping." He stuck them to restroom walls around the city.

"I believe many people in China feel the same way as I do. Most of the people around me are also disgusted, but they are afraid to act," he said, speaking on the condition of anonymity for his continued security.

As with similar movements, the protesters face divisions among themselves. In London, Wu is not all that optimistic about the change they might ultimately bring about. Protesting is more complicated than she expected.

Some within the group disagree with Hong Kong demonstrators who are calling for independence. Wu is concerned about conditions for women in China, but the men dismissed that issue.

"I'll do whatever I can for now," she said after attending a protest in London's Trafalgar Square late last month. Still, she has learned one invaluable lesson: "It turns out courage is something that can be practiced and built up."

Kuo and Chiang reported from Taipei. Yu reported from Hong Kong.