Owen L. Conner, curator for the National Museum of the Marine Corps, unwraps pieces of a wooden cross bearing the name of Sgt. Bernard A. Marble, 28, of Massachusetts, one of more than 1,000 Marines who died in the 1943 battle for Tarawa. (Katherine Frey/The Washington Post)

QUANTICO, Va. — Curator Owen L. Conner carefully unties the ribbon around the weathered slats and removes the storage paper. Sand from the island where the Marines fought still clings to some of the wood. One by one, he assembles the three crosses once used to mark graves.

As he does, the faded names appear in black over peeling white paint: Robert W. Hillard; Clarence S. Hodgson; Bernard A. Marble. Fragments of other names can be seen on other pieces, and "Nov . . .1943."

The crosses come from lost cemeteries on the World War II battlefield of Tarawa, an atoll in the Pacific where more than 1,000 Marines were killed fighting the Japanese, and where hundreds may still lie buried in unmarked graves.

Last month, the National Museum of the Marine Corps officially acquired the crosses, along with other grave artifacts, from History Flight Inc., the Fredericksburg, Va., nonprofit archaeological firm that has been excavating on Tarawa for more than a decade.

The Tarawa crosses are rare and are believed to be the only such artifacts in a museum collection.

The relics from a bygone war come as the Marines mourn the 11 members killed in the most recent conflict, alongside one soldier and one sailor, in the Aug. 26 suicide bombing attack at the Kabul airport.

Among the items from Tarawa: A projectile removed from the lower back of a skeleton; a pristine glass ampule of iodine; a tiny glass bottle containing unidentified pills; a container of surgical thread; a deteriorated poncho of the kind bodies were buried in; and Japanese and American helmets and canteens.

The crosses had been wrapped up like a bundle of old fence parts and stored in a repository on the atoll when they were spotted three years ago by History Flight's chief operating officer, Justin D. LeHew.

One day last week, Conner, the museum's curator of uniforms and heraldry, unboxed the crosses and other artifacts in the museum's support center in the old brig on the Marine base here.

He said he hoped some of them might soon be displayed at the museum.

The crosses all told tragic stories.

The United States assaulted the Japanese-held atoll - mainly its tiny island of Betio - over four days in late November 1943. The attack was part of the plan, after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, to seize enemy bastions across the Pacific Ocean.

But Betio, code named "Helen," was heavily fortified, and defended by about 4,500 men. A Japanese admiral reportedly bragged that a million Americans couldn't take it in 100 years. The Marines had about 18,000 men.

The battle was fierce, and often fought at close quarters.

Color film footage shot by a Marine cameraman captured the grim nature of the combat and its aftermath. In one clip, the bodies of Marines are seen strewn across the beach and floating in the water.

The handling of the dead was haphazard.

Part of a wooden cross bearing the name and service number of Marine Clarence Hodgson, recently donated to the National Musem of the Marine Corps. (Katherine Frey/The Washington Post)

"Corpses were everywhere," Pfc. Joe Jordan recalled, according to historian Derrick Wright. "We worked to identify the folks from our unit and placed them in the trench covered by their ponchos . . . Then bulldozers pushed sand in on top of the bodies."

Graves were scattered across the island, some apparently denoted with markers, some not, according to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA).

Military construction projects later moved many grave markers without moving remains, a DPAA historian has written.

In addition, other markers appear to have been placed where there were no bodies. And some markers were erected to commemorate Marines who died of wounds and were buried at sea.

In 1946, graves registration experts exhumed remains from 43 cemeteries and burial plots across the island and combined them into one.

In late 1946 and early 1947, the combined remains were disinterred again, and the markers apparently discarded.

The human remains, at this point mainly skeletal, were taken to Hawaii for possible identification, and in 1949, those unidentified were reburied in a national cemetery in Honolulu.

In the overall process, though, half the Marine dead may have been left behind on Betio, according the DPAA.

Last week, the crosses of Hillard, Hodgson, and Marble looked like pieces of driftwood as Conner, the curator, put them together on a display table.

He matched up the name, rank and serial numbers written on the broken sections as if working on a puzzle.

As he worked, he said he often wonders about the men: Who was Robert Hillard? "Where'd he come from? . . . What did he look like?"

"The really tragic thing with these men [is] so much of their stories have been lost," he said. "Because they didn't have . . . their own young families and their parents were the only people that they had, and they're gone."

"You just sort of have these dead ends on their lives," he said. "When I see those crosses I think how sad their ending is."

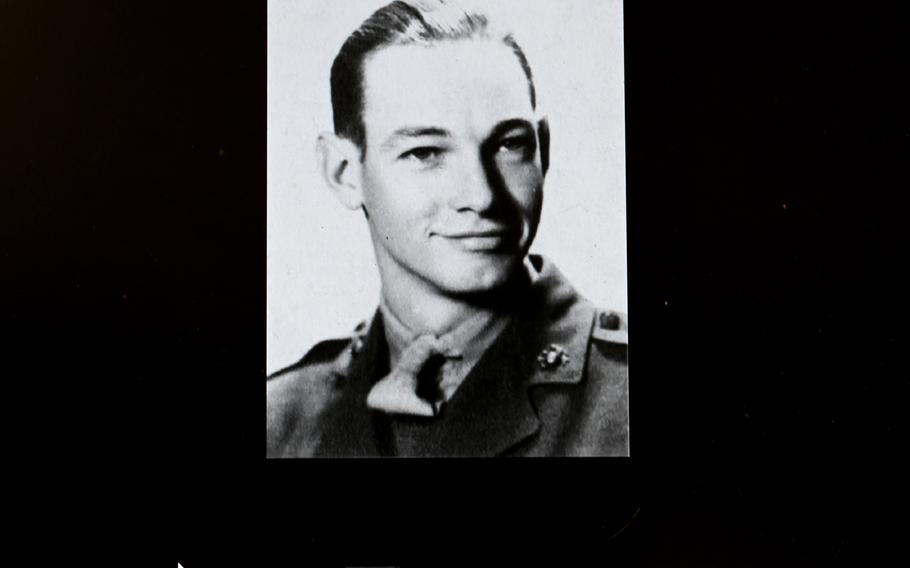

A photograph of Marine Pfc. Robert W. Hillard, 19, of Arkansas, is seen on a computer screen at the National Museum of the Marine Corps. (Katherine Frey/The Washington Post)

Hillard, a native of West Tulsa, was one of 11 children and stepchildren in a blended farming family in Big Fork, Ark., according to census records.

He was 17, technically a minor, when he enlisted in 1941. He needed his mother's consent to sign up.

He was 19 when he was shot in the head and killed on Nov. 20, 1943, according to government records gathered by private researcher Geoffrey Roecker.

Hillard was one of 61 Marines from his 165-man company killed in the battle, Roecker said in an email. They were shot down as they tried to land on an especially deadly section of beach called "the pocket."

His family was not notified of his death until Jan. 1, 1944. And his body was not recovered.

But after the war, his mother, Susie Ratliff, said the Marines sent her a package of his belongings - a cigarette case, a pocket watch and wallet, and mistakenly informed her that he was buried in "grave 9, row 1, plot 10" of a Marine cemetery on Betio.

In 1947, the Corps reversed itself, apologizing and telling her that it had not found her son's body under his grave marker - the same one, perhaps, that Conner had on his display table.

"It must be assumed that . . . the cross was erected in his honored memory rather than . . . as a marker identifying the location of his grave," the Marine Corps commandant wrote her.

She was livid.

"Why have I been deceived?" she wrote a local congressman. "Why didn't they tell me the cold hard facts in the beginning so I could accustom myself to them all at the same time? . . . [It's] more than I can sanely take."

Clarence Stanley Hodgson, of Eddyville, Iowa, had just turned 18 when he enlisted in the Marines in 1940. He was known as Stanley, and was the son of a farmer. He was 21 when he was shot in both legs on Nov. 21, 1943.

A photograph of Marine Clarence Hodgson of Iowa is viewed on a computer monitor at the National Museum of the Marine Corps. (Katherine Frey/The Washington Post)

He was evacuated to the USS Sheridan, a troop ship, where doctors amputated part of his right leg. He was given whole blood, blood plasma and a solution of saline dextrose.

But he "failed to respond to treatment," the government records state. He died at 9 p.m. the next day and was quickly buried at sea.

He got a memorial cross on Betio despite the absence of his body.

Sgt. Bernard A. Marble was 28 when he was killed Nov. 21. His battalion had suffered heavy casualties as it came ashore the day before on Red Beach 3.

A native of Somerset, Mass., where he lived a block from the Taunton River, he had enlisted on Sept. 19, 1941, according to the records.

His body was recovered and buried in a large grave on Betio. It was later exhumed and reburied in the combined grave. It was identified. Its location was recorded, and a grave cross was created.

It's not clear what happened after that, but when his remains were exhumed again and moved to Hawaii, they were classified as unknown. At that point they consisted mainly of a skull, arms, chest and pelvis, according to government files.

Laboratory examination of his dental records and physical characteristics, though, enabled experts to identify the body as Marble's.

He was returned to Somerset and on May 12, 1949, five years after his death, he was buried in a cemetery around the corner from his home. The funeral flag was presented to his mother, C.

The crosses and artifacts were unearthed during History Flight's work with the DPAA on Tarawa over the past few years, said LeHew. The chief aim of the project was to locate lost gravesites and to repatriate and identify remains of Marines buried on Betio.

About 140 sets of remains have been recovered and identified. As many as 400 may still be there, according to the DPAA.

Over the years, a large cache of artifacts - American and Japanese - had also been unearthed, LeHew said: things like rusted rifles, helmets and burial markers.

"It was all pretty much relic status," he said. "But for the trained eye . . . it was the entire battle history of the U.S. Marine Corps of that time period."

During his visits to the site, which is 2,400 miles southwest of Hawaii, he said noticed that some pieces were starting to deteriorate.

"I knew I had to do something to preserve this," he said. He inventoried everything not needed by the DPAA experts, and set aside the most historic and intact Tarawa artifacts.

He brought them back to the U.S. and offered them to the museum.

The museum accepted them all.