()

WASHINGTON — If the deteriorating situation at a Japanese nuclear plant veers toward a worst-case meltdown scenario, people across the country — including 86,000 American servicemembers, civilian employees and their dependents — could face an unprecedented atomic disaster.

The Pentagon on Wednesday began laying out precautions to keep troops safe, announcing a 50-mile no-go zone around the unstable Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear complex that is wider than the official Japanese evacuation zone. The U.S. Embassy in Japan told American citizens within 50 miles of the plant to evacuate if possible or stay indoors.

Meanwhile, military doctors began advising U.S. air crews flying rescue missions within 80 miles of the stricken complex to take potassium iodide tablets to combat harmful radiation effects. Already, troops on some bases in Japan and aboard ships offshore — including two air crew members on the USS Ronald Reagan who had to take iodide tablets Tuesday — have been exposed to radiation from the nuclear plants, although at levels not believed high enough to pose a serious risk.

Despite the precautions, there is no single Pentagon policy that determines how much radiation troops should be allowed to endure before they must be evacuated. Instead, the judgment is left to individual commanders. Several Pacific commanders contacted by Stars and Stripes for clarification referred questions back to the Pentagon.

In Washington, a spokesman for the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs referred questions about permissible radiation exposure levels to Pentagon media staff.

"We train and equip all of our people to operate in all kinds of environments," Pentagon spokesman Col. Dave Lapan said. "We know how to measure, we know how to test, we know how to take precautions."

Dr. Fred Mettler, a leading expert on the effects of radiation and a radiologist at the New Mexico Veterans Health System, oversaw a 1999 Institute of Medicine study that led to the recommendation against a single stringent Pentagon policy governing battlefield radiation exposure.

"Commanders should always seek to minimize the dose in the context of the requirements of the mission," Mettler said in an interview. "Think of it like getting shot. Do you have a guide to how many bullets a soldier should be allowed to take?"

The 1999 report, however, doesn't address the question of what the military should do when entire bases are downwind from an unstable reactor, as is the case in Japan.

Some nuclear experts are now saying the Fukushima crisis could rival the 1986 Chernobyl disaster in the former Soviet Union.

Nuclear scientists use the term "core-on-the-floor" to describe radioactive fuel burning through protective containment layers, hitting water and bursting into the atmosphere in a huge steam explosion, spreading clouds of radioactive gas and dust.

It's never happened before, but experts fear it may soon become reality in one or more reactors at the Fukushima nuclear complex, which was gravely damaged in last Friday's 9.0-magnitude earthquake and ensuing tsunami.

"We are right now closer to core-on-the-floor than at any time in the history of nuclear reactors," said Kenneth Bergeron, a former Sandia National Laboratory researcher who spent his career simulating such meltdowns, including in reactors of the type at the Fukushima plant.

Even in such a scenario, only people very near the plant — and well inside the 12-mile exclusion zone the Japanese government has set up — would be in danger of burns and other acute radiation effects, experts say.

But on U.S. bases hundreds of miles away, people still would need to take quick steps to limit exposure or else risk long-term cancer effects.

In the most devastating nuclear accident to date, at Chernobyl, there was no meltdown. Instead, the reactor exploded and burned for days, hurling radioactive dust laced with cesium, strontium, and radioactive iodine high into the air, which later menaced broad swaths of Europe as the materials fell back to Earth.

If one or more of the Fukushima reactor cores melt out of their containment vessels, the release could be smaller and less violent. But whether the effects would be less risky than Chernobyl, which officials estimate killed 50 people initially and will eventually lead to the cancer deaths of thousands, is an open question.

Fukushima "could even be more dangerous, depending on wind and weather," said Bergeron, who is now a nuclear safety consultant and writer.

Large concentrations of radioactive material were found hundreds of miles away from Chernobyl's ground zero, said Mettler, who, as the U.S. representative on radiation danger to the United Nations, was deeply involved with Chernobyl.

"What tends to go out are the things that are volatile, or gases," he said. "Cesium 137 can easily go hundreds of miles."

That means they could hit U.S. bases after a meltdown. Defense Department policies require commanders to have emergency procedures for distributing potassium iodide and Prussian blue, medications that block the uptake of radioactive iodine and cesium, respectively.

Prussian blue is stocked regionally at Trippler Army Medical Center in Hawaii. The Pentagon said Wednesday it has enough iodide on hand in Japan.

Even in its current state, Fukushima has released radiation measurable on U.S. bases. A measurement of 20 millirems of radiation exposure over 12 hours was made at Naval Base Yokosuka, not Naval Air Base Atsugi, although officials at the time recommended personnel at both locations take precautions.

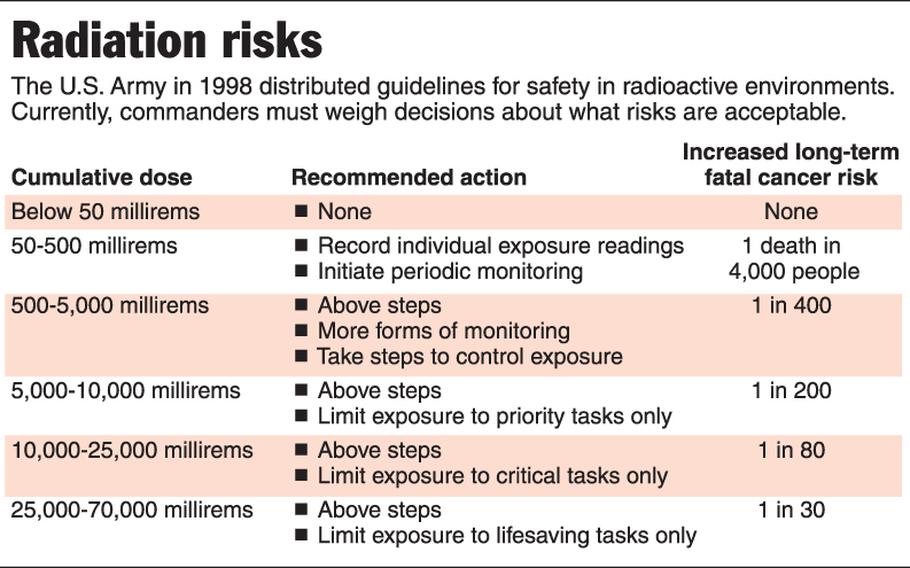

Though health officials agree that's not a harmful level in itself, it could become serious if it becomes a pattern. A 1998 U.S. Army guideline on low-level radiation set 50 cumulative millirems as a threshold at which exposed individuals should begin being monitored for harm.

From 50 to 500 millirems, one extra cancer death will occur in a population of 4,000 people, according to the Army's data. The next threshold is 500 millirems, at which an extra cancer death will in a group of 400 people.

Though they won't talk about specific disaster plans, base officials in Japan are trying to ease concerns among their military communities.

In Misawa, Air Force officials have repeatedly told residents they are in no danger of radiation from the failing nuclear reactors in Fukushima, which is about 240 miles south of the base.

"I am not moving my family out or secretly taking iodine pills," Col. Michael Rothstein, the base commander, told Stars and Stripes Wednesday. "There is no threat here."

Rothstein took that message on the radio with a live address Tuesday night as radiation from the Fukushima nuclear plant spread to U.S. military bases in central Japan.

"My sense is there is a challenge reaching everybody with the message," but residents are trusting reassurances from the base command, Rothstein said. Col. Guillermo Tellez, commander of the 35th Medical Group at Misawa, emphasized that there is no threat of radiation exposure and the base has gotten no direction from the Air Force to distribute potassium iodide.

Though it may strike some as glossing over a bad situation, many experts believe that the fear of being exposed to radiation can be more damaging than the radiation itself, leading to depression, substance abuse and other ills.

After Chernobyl, for instance, a multiparty study group including U.N. agencies and national governments concluded in 2005 that many thousands of people had been scarred psychologically by the event.

Mettler, the Chernobyl expert, offered some cold comfort to residents of the potential fallout zones.

"Japan just lost 10,000 or 20,000 people in the tsunami and earthquake," he said. "The worst this [nuclear] situation can possibly get — in short-term and long-term effects — still can't come anywhere close to that."

Stars and Stripes reporters Kevin Baron, Travis Tritten, Ashley Rowland and Erik Slavin contributed to this report.