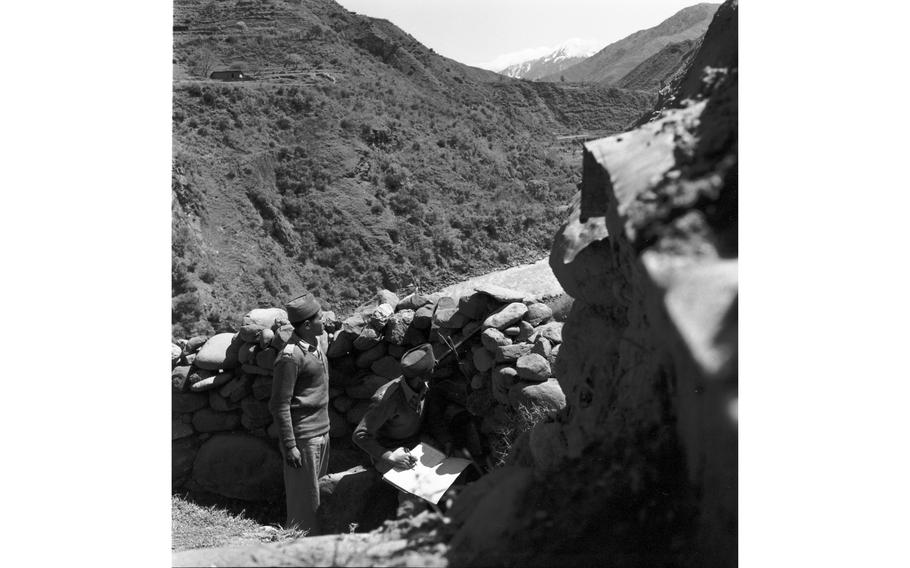

Observers look out towards India, over the Kashmir ceasefire zone between India and Pakistan. Stars and Stripes reporter John Wright wrote: "From the check-point on the Pakistan side it is possible to look across the little stream and watch the Indian troops who man their barrier on the opposite bank." (Ted Rohde/Stars and Stripes)

This article first appeared in the Stars and Stripes Europe edition, June 17, 1958. It is republished unedited in its original form.

War is only a trigger’s squeeze away along the seldom-remembered cease-fire line that divides the former Princely State of Kashmir.

For nearly 10 years, two powerful armies — the most powerful in the smoldering East — have faced each other across a scant 500 yards of no-man’s land. From one side Indian army forces, augmented by brigades from Jammu and Kashmir, look across at the Muslims of Pakistan and Azad (Free) Kashmir, each defiant of the other in a dispute that has defied UN mediation for almost a decade.

Extending for nearly 400 miles from the upper reaches of the Indus River to the glacial highlands of the Himalayas, the Kashmir cease-fire line is a living reminder of fighting that started in the late summer of 1947, soon after the partition of the Indias subcontinent.

A million people lost their lives in an undeclared war that ravaged the princely state., including the beautiful Vale of Kashmir, until a UN-sponsored cease-fire in January 1949.

Since then, mediation of the touchy issue — one based on religion and nationalism — has failed.

The early stages of fighting in Kashmir are completely shrouded in controversy, but it seems to have started in a number of isolated places at about the same time. At first it was not warfare at all, but armed attacks on one village with consequent retaliation on a similar village by the opposition.

Pitched warfare came when a band of armed tribesmen were advancing on Srinagar, the capital of Kashmir.

By force of arms against the Muslim irregulars, Indian airborne troops gained control of most Kashmir, until they were stopped in their unequal drive, first by guerrilla forces and later by Pakistan’s troops.

The UN was asked to settle the issue and a cease-fire line was drawn that has been observed — more or less — while mediation — so far unsuccessful — continues.

The cease-fire agreement permits each side to man the line on their respective sides restrains them from any increase in military potential over that in effect at the time the agreement was signed.

In general no troops are to approach within 500 yards of the line. However, there are some exceptions. Similarly the firing of weapons, repair of fortifications and photography of installations are prohibited.

On the Pakistan side farmers are permitted to cultivate their plots up to the demarcation line, but they too are prohibited from crossing.

A typical check post on the cease-fire line is one on the banks of the Jhelum River, north of Muzaffarabad in western Kashmir.

Here, on what used to be the main road from Rawalpindi in Pakistan, to Srinagar in Kashmir, participants in this undeclared war face each other across a dry stream bed that forms the demarcation line separating Indian-held territory from Azad Kashmir.

From the check-point on the Pakistan side it is possible to look across the little stream and watch the Indian troops who man their barrier on the opposite bank.

The road once made a horseshoe bend, but the bridge that spanned the dry wash was destroyed during the war and has not been rebuilt. Instead a narrow dirt fill and culvert replaces the bridge so that white UN jeeps — the only traffic that crosses between the belligerents — can go back and forth between UN check points on either side.

The meandering cease-fire line can be followed on a map of Kashmir that hangs on the wall of a former maharajah’s rest house in Domel [Domail] where the UN now has a field station.

Starting a few miles east of Jhelum, on the Pakistan-Indian border, the line runs northward through the lower foothills that are the stepping stones to the Himalayas. After a couple of reverse bends in an area known as Punch, it crosses the Muzaffarabad-Srinagar road and Jhelum River at a streamside check-point.

From there, the line slices through mountains in a northerly direction until it meets the Kishanganga River where it turns east to lose itself in the glaciers of Ladakh, near the Sinkiang [Xinjiang] border.

Indian forces hold the territory south and east of the line and Pakistan defends the region north and west.

The jeep ride from the UN field station to the cease-fire line is uneventful except for the claustrophobic feeling of being sandwiched between the Jhelum River, 1,000 feet below and the cloud-scraping mountains above. On every available flat place, Kashmir famers till their terraced lots of rice and wheat.

Military activity in the region is nil with the exception of occasional cease-fire line patrols. Pack-mule stables and camel caravans of supplies remind the visitor to the area is a military zone.

The officers and men who man the front are relaxed and casual, but constantly on alert to an overt move by the opposition.