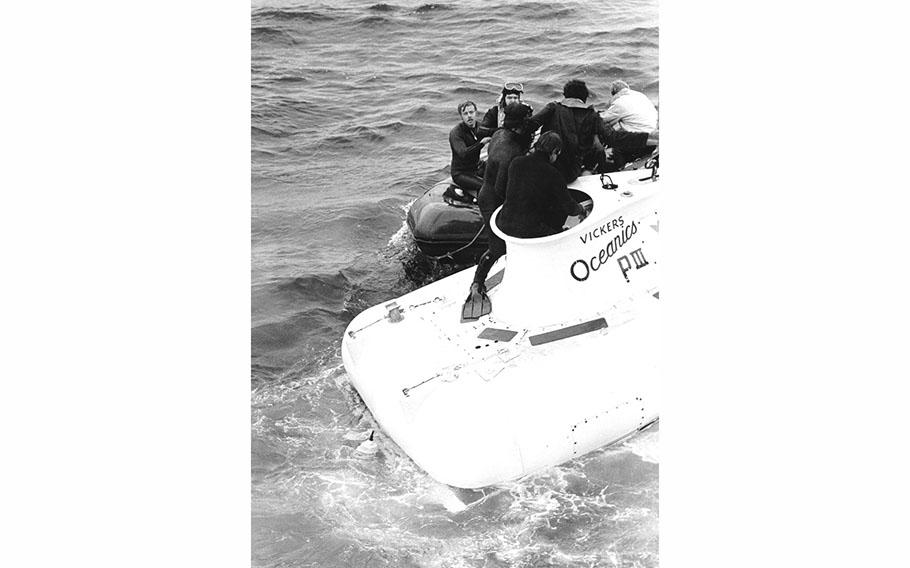

Divers assist rescued pilots from the Canadian submersible Pisces III in September 1973. (U.S. Navy)

A small two-person Canadian submersible was being hoisted to the surface by its mother ship off the coast of Ireland when things went wrong. A hatch was accidentally yanked open by the mother ship's A-frame lift, filling a part of the watercraft with two tons of seawater.

The submersible instantly sank to depths of almost 1,600 feet.

But three days later, on Sept. 1, 1973, Roger Chapman and Roger Mallinson emerged alive, making their rescue the deepest ever achieved.

Fifty years later, the five-person Titan submersible is missing, potentially at a much greater depth. It lost contact with its surface ship almost two hours into a dive to explore the wreck of the Titanic at 12,500 feet.

Going under the sea "is one of the most difficult tasks" people can undertake, said Roger Litwiller, a Canadian naval historian. "The latest technology is ever evolving. But still, the bottom of the ocean is still the bottom of the ocean. We know more about the moon."

Chapman and Mallinson's submersible, the Pisces III, was a two-compartment vehicle conducting a routine mission to lay sea cable. As it was being pulled to the surface by its mother ship, the Vickers Voyager, the hatch to its rear compartment was unintentionally opened, completely flooding that part of the craft. The submersible instantly sank to the bottom, 1,575 feet underwater, with 72 hours of oxygen left in the ship.

The two crew members were maritime professionals, having served in the British navy. They also benefited from having not lost communications, allowing them to tell their colleagues on the surface that they were "in good physical condition, with adequate water and a little food," according to an account by the U.S. Navy, which participated in the rescue.

A rescue began almost instantly, grabbing the world's attention for the three-plus days it took to pull Chapman and Mallinson back to the surface. Rescuers ordered them to stretch their oxygen supplies by remaining "as inactive as possible." This meant they hardly spoke or moved. That strategy enabled them to stretch their initial 72-hour oxygen to about 84 hours.

"They basically shut everything down, including themselves," Litwiller said. "They basically hibernated."

"In a situation like this, every minute counts. When the Pisces III was brought to the surface, the oxygen they had left equaled 12 minutes. So for the Titan, it's not over," Litwiller added. The concern about the Titan is that its crew includes tourists, who may not be knowledgeable about methods of reducing oxygen consumption, Litwiller said.

During the rescue of the Pisces III, Chapman and Mallinson's colleagues quickly organized an international rescue effort involving aircraft and ships from Britain, Canada and the United States.

Likewise, the U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Navy, Canadian Coast Guard and OceanGate Expeditions, the company that operates the Titan, have created a unified command. French experts who can control remotely operated vehicles that can dive deep into the ocean were also on their way, U.S. Coast Guard Capt. Jamie Frederick told reporters.

But for the Titan's searchers, locating the vehicle appears to be more difficult than for those who participated in the 1973 rescue. As the Titan's oxygen supply dwindles, rescuers are combing through an area twice the size of Connecticut. Rescuers are also unsure whether the Titan is on the surface, on the seabed or somewhere between, The Washington Post has reported.

The Pisces III, on the other hand, was able to maintain communications with surface rescuers, and the mother ship was able to retain sonar contact with the submersible, allowing it to release two buoys to mark the approximate location of the underwater vehicle.

After rescuers attached specially designed toggles to the Pisces III via cable-controlled underwater recovery vehicles, or CURVs, the submersible was tugged to the surface. Once pulled out of the craft, Mallinson and Chapman took in a breath of fresh oxygen, smiling and waving.

Mallinson, who is now in his 80s, said in an appearance on Britain's Sky News this week that he fears "something might be seriously wrong" for the crew members of the Titan because they have not been able to send out a signal. "I would have thought a hammer on a bit of a hole somewhere would be a good transmitter, and it would carry."