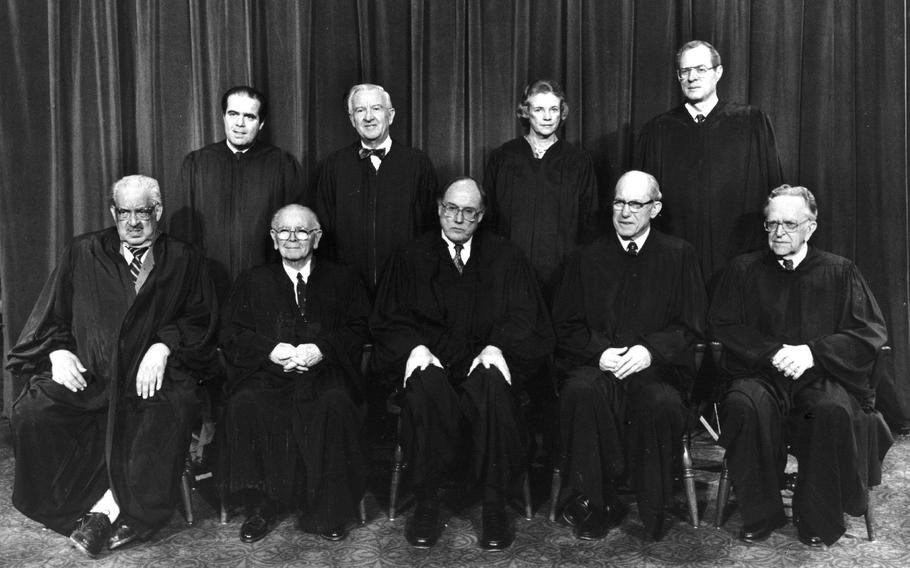

Official portrait of the Supreme Court in April 1988. The first two seated justices on the left, Thurgood Marshall and William Brennan, both retired under Republican President George H.W. Bush, shifting the court rightward and putting Roe v. Wade in danger. (James K.W. Atherton/The Washington Post)

The prospect that the Supreme Court could soon overturn Roe v. Wade has some abortion rights supporters wishing liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had heeded pleas from Democrats to retire while the party controlled the White House. President Donald Trump's replacement of Ginsburg with Amy Coney Barrett cemented a powerful conservative majority on the court, probably altering abortion rights for a generation.

But three decades ago, two liberal justices made an even more surprising decision: They retired under a Republican president. And many observers were convinced they that doomed Roe to be overturned.

When Thurgood Marshall, the first Black justice, retired in June 1991, President George H.W. Bush replaced him with Clarence Thomas. The change gave the court not just another conservative vote, but also a beacon for a hard-right worldview, whose opposition to abortion has now taken firm root on the court. Justice Samuel Alito Jr.'s leaked draft opinion that would overturn Roe cites half a dozen of Thomas's previous opinions.

Marshall's retirement caught everyone off guard. Marshall, nominated by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967, had always called his job a "lifetime term" from which he would never retire.

"Marshall never talked about retiring, even vaguely," said Susan Low Bloch, a Georgetown Law professor and former clerk for Marshall. "I remember being very surprised when he announced it. It came out of the blue."

Had Marshall stayed on the court for another 1 1/2 years, a Democratic president, Bill Clinton, would have chosen his successor. (As it turned out, Marshall died four days after Clinton's inauguration.)

Marshall's surprise retirement came a year after his good friend and fellow liberal Justice William Brennan stepped down, allowing Bush to appoint David Souter, whom White House chief of staff John Sununu called a "home run for conservatives." The twin departures left the court with just one justice who had been nominated by a Democratic president: Byron White, who was conservative on many issues and had voted against Roe in 1973.

It was a shocking transformation for a court that, when it unanimously struck down public school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, had only one GOP-nominated justice. (Marshall successfully argued that case on behalf of the NAACP.)

And it seemed to put Roe in grave danger.

So why had Marshall decided to step down such a short time before the end of Bush's term?

He gave a simple reason: At 83, he was getting old. "The strenuous demands of Court work and its related duties required or expected of a Justice appear at this time to be incompatible with my advancing age and medical condition," he wrote, employing the exact language Brennan had used in his resignation letter.

Or as Marshall later put it: "What's wrong with me? I'm old! I'm getting old and coming apart."

But there was a political factor, too. In the middle of 1991, few strategists thought a Democrat could win the next year's presidential election. Republicans had occupied the White House for all but four years since 1968. And Bush was popular, fresh off the U.S. victory over Iraq in the Persian Gulf War.

"Calculations that President Bush is a prohibitive favorite to win reelection in 1992 have not changed, but Democratic strategists increasingly are viewing 1992 as the platform for 1996 — when most expect the Democrats' presidential prospects to be much brighter," Ronald Brownstein wrote in the Los Angeles Times in May 1991.

"Bush looked pretty invincible," recalled Bloch, who served as a pallbearer at Marshall's funeral. If Marshall thought Democrats had a good chance to win back the White House, she said, she is "100% certain" he would have stayed on the court.

After Bush named Thomas to the seat, the Senate confirmed him 52-48, following accusations of sexual harassment by Anita Hill.

Just as now, Democrats fretted about the court's conservative direction and the threat to Roe. Rep. Les AuCoin, D-Ore., said when Marshall announced his retirement, "Sadly, I believe it's also the final chapter in the high court's protection of reproductive rights in particular and the right to privacy in general."

So far, Souter seemed likely to vote against Roe. After one year on the bench, the New York Times wrote that Souter "has proven to be among the more conservative members of the Court on decisions like the recent one allowing the Bush Administration to prohibit family planning clinics that receive Federal funds from advising women about the availability of abortions."

But Souter wound up saving Roe, almost exactly one year after Marshall announced his retirement. In a June 1992 case concerning a Pennsylvania abortion law, the court in Planned Parenthood v. Casey affirmed Roe's "central holding," while allowing states to impose some new restrictions on abortion. Souter co-wrote the opinion with Sandra Day O'Connor and Anthony Kennedy — both nominated by Ronald Reagan, a staunch abortion foe.

Overturning Roe, the three justices wrote, would come "at the cost of both profound and unnecessary damage to the Court's legitimacy and to the Nation's commitment to the rule of law."

Thomas joined three other conservative justices in calling for Roe to be ruled unconstitutional.

Meanwhile, the court's remaining liberal justices — Roe author Harry Blackmun and John Paul Stevens — joined the court's opinion in part, providing the margin for the 5-4 ruling. Each wrote an opinion arguing the court should have struck down the Pennsylvania restrictions.

Blackmun and Stevens had been nominated in the 1970s by Republican Presidents Richard M. Nixon and Gerald Ford, respectively, a sign of how much less politicized — and scrutinized — Supreme Court nominees had been in that decade. Blackmun acknowledged the changing times in his opinion.

"I am 83 years old," he wrote. "I cannot remain on this court forever, and when I do step down, the confirmation process for my successor may well focus on the issues before us today."

In the last 30 years, four liberal justices have retired, and each timed his departure so that a Democrat could name his replacement. Blackmun retired in 1994, paving the way for Clinton to nominate Stephen Breyer. This year, the 83-year-old Breyer retired, allowing President Joe Biden to choose his successor, Ketanji Brown Jackson.

As for Souter, who became a reliable liberal vote, The Washington Post reported during the 2008 campaign that he told a friend, "If Obama wins, I'll be the first one to retire." He did just that, allowing President Barack Obama to replace him with Sonia Sotomayor in 2009. The next year, Stevens retired, and Obama named Elena Kagan to his seat.

The decisions by Marshall and Brennan to retire under a Republican president are clearly from another era.

"It wasn't lost on either Brennan or Marshall that there was a Republican president who would nominate someone that they might not want to see sitting in their seat," Bloch said. "But it was a different time — they were not as focused as much as they are now on who would replace them. It wasn't as strategic and planned as it looks now."