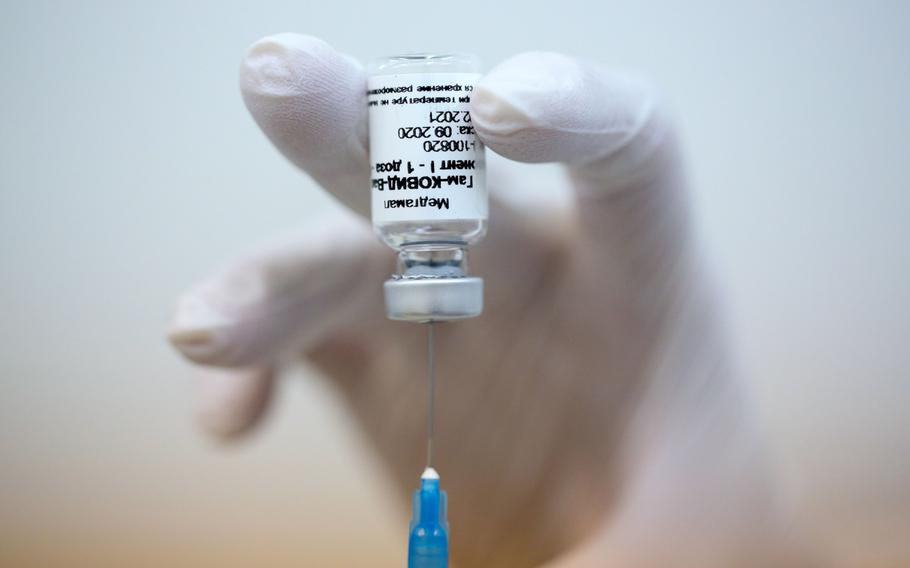

A heath worker draws the ‘Gam-COVID-Vac’, also known as ‘Sputnik V’, COVID-19 vaccine, developed by the Gamaleya National Research Center for Epidemiology and Microbiology and the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) at a clinic in Moscow on Sept. 23, 2020. (Andrey Rudakov/Bloomberg)

The United States announced last week that it would soon open its doors to foreign travelers vaccinated against COVID-19, loosening restrictions for broad swaths of global visitors for the first time since the pandemic began.

But the new rules, set to take effect in November, appear to also shut out many people who consider themselves to be fully immunized — including millions who have received two doses of Russia's Sputnik V vaccine.

Hundreds of thousands of Russians could be directly affected. Despite frosty diplomatic relations and limited demand for international travel, roughly 300,000 Russians visited the United States in 2019, the last year for which figures are available, according to the U.S. Travel Association.

More broadly, the U.S. plan is another blow for the manufacturers of Sputnik V, which Moscow has proudly proclaimed as the first COVID-19 vaccine to be registered for use. Though the vaccine was intended to be a powerful tool of pandemic diplomacy, its limited acceptance abroad and slow rates of delivery have left it behind not only Western vaccines but also those made by Chinese manufacturers.

"This is a big problem for Russian travelers and for people in other countries who've received Sputnik V," Judyth Twigg, a professor at Virginia Commonwealth University who tracks public health in Russia, said of the new U.S. rules in an email.

The Russian Direct Investment Fund, the sovereign wealth fund that backed Sputnik V, said in a statement that the vaccine had "not only … been approved in 70 countries where over 4 billion people, or over half of the world's population, live, but its efficacy and safety have been confirmed both during clinical trials and over the course of real-world use in a number of countries."

"We stand against attempts to politicize the global fight against COVID-19 and discriminate against effective vaccines for short-term political or economic gains," the statement continued.

The new U.S. plan requires that most noncitizens seeking entry to the United States are vaccinated with shots approved for emergency use either by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or World Health Organization. That includes vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna, as well as shots developed by Chinese firms such as Sinopharm and Sinovac.

But Sputnik V, an adenovirus vaccine developed by the Moscow-based Gamaleya Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology, has yet to be approved by the WHO. The global health agency this week said that it suspended its review process of the vaccine, citing concerns over the manufacturing practices at production plants inside Russia and whether the vaccine can be consistently produced to the necessary standard.

Speaking at a conference in Vladivostok this month, RDIF head Kirill Dmitriev said that "mutual recognition of vaccines is the issue of this year" and claimed that a "number of 'Big Pharma' companies intentionally, as a matter of competitive rivalry, are attempting to restrict Sputnik and absorb markets," according to Russian news agency Tass.

Unlike other nations, the United States did not have blanket restrictions on travel from Russia before this announcement, meaning all travelers from the country that tested negative for COVID-19 could be allowed into the United States under CDC guidelines. That will change in November, just as doors open to millions of travelers from Europe and elsewhere.

The new U.S. rules will not only affect Russians. According to data from the Global Health Innovation Center at Duke University, some 448 million Sputnik V doses have been purchased worldwide, with many going to low income nations. Some governments have complained of slow deliveries from Russia. The limited options for travel are likely to further criticism of the Russian drug.

"Russia's squandered an opportunity to use this vaccine as a diplomatic tool," Twigg said, citing the production issues around Sputnik.

The Russian Embassy in Washington declined to comment on the new U.S. policy.

Sputnik V is not the only vaccine facing risk of being left behind. Neither the FDA nor the WHO have authorized India's Covaxin, which has seen 560 million doses purchased so far, mostly in India. Those vaccinated with Covaxin may not be allowed to visit the United States in November. There have also been disputes with individual governments not accepting some vaccines, such as Britain's refusal to fully recognize vaccines administered in many parts of the world.

But for Sputnik V, a vaccine that has taken a brash and sometimes confrontational approach to its rivals, the failure to secure World Health Organization emergency use listing or a similar listing by the European Medicines Agency, an E.U. body, has been a big reputational blow.

Despite the recent suspension of the WHO approval process, RDIF said that "Russia's Health Ministry is in constant contact with WHO experts on the approval process and we remain confident Sputnik V's approval by the global health regulator is imminent due to the vaccine's outstanding track record."

Some immunization experts have broader fears that the U.S. move and others like it could create two classes of vaccinated people around the world: one that is able to travel freely and the other not. In Russia and other countries, travel firms have already started offering wealthy customers trips abroad, including to places such as Serbia, so that they can get vaccinated with more widely-accepted shots.

Alexander Gabuev, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Moscow Center, said that there was a growing frustration among "those with money and power" that their vaccines were not more widely accepted. Some spread "conspiracy theories," Gabuev said, including one that "everybody envies Russia as the nation that developed the first vaccine" and so Western powers conspired against Sputnik V.

The WHO approval for Chinese vaccines, such as Sinopharm and Sinovac, undercut that message. Though Sputnik V appeared to provide stronger protection than these China-backed vaccines, Russia's role as a vaccine exporter had been severely limited by production issues and China had emerged as a more reliable partner, Gabuev said.

"The approval of the World Health Organization adds to the credibility of Chinese vaccines as opposed to the Russian vaccines," he added.