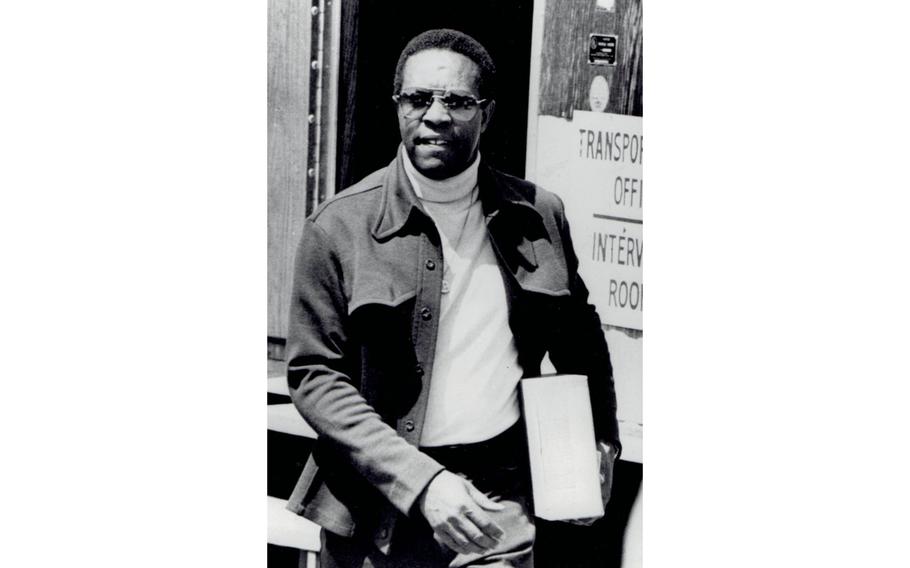

Lee Elder in 1975. Elder, an Army veteran who shattered one of golf’s last racial barriers when in 1975 he became the first African American to compete in the tradition-bound Masters tournament in Augusta, Ga., has died at 87. (Wikimedia Commons)

Lee Elder, an Army veteran who shattered one of golf’s last racial barriers when in 1975 he became the first African American to compete in the tradition-bound Masters tournament in Augusta, Ga., has died at 87.

The PGA Tour announced the death but provided no further details.

Elder’s much-heralded triumphs on the green followed a turbulent start in life. He was orphaned at 9, dropped out of high school in Los Angeles in 10th grade and supported himself as a caddie and a golf hustler, often in cahoots with the noted gambler and golfer Alvin Thomas, better known under the pseudonym Titanic Thompson.

He sometimes posed as a caddie for Thompson, who was white, or as his liveried chauffeur. Thompson would take wagers that he and his chauffeur could defeat the two best players on the course. At the end of the day, they often walked away with a handsome profit.

“I knew it was dishonest, but there are times when you have to forget about dishonesty when you want to survive,” Elder once told The Washington Post.

It took years of struggling against the discriminatory barriers of professional golf before he was allowed to compete against white golfers and to take his place at Augusta and in other prestigious tournaments.

As a hustler, Elder had played courses on his knees, on one leg or wearing a raincoat on a brutally hot day (albeit with ice-cold towels concealed within) — all manner of outrageous handicaps to rake in a living wage. He made hundreds, sometimes thousands of dollars at a clip.

But it was his raw talent, on display during an exhibition match in Cleveland with former heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, that brought Elder to the attention of his first mentor, Ted Rhodes.

Rhodes, Louis’s personal golf instructor, had competed in the U.S. Open in 1948 and was one of the first Black professional golfers. Rhodes persuaded Elder to switch from an unorthodox cross-handed grip to a conventional grip, dramatically improving his game. He moved into the Rhodes home in St. Louis for three years and accompanied him on trips to Havana and Kingston, Jamaica — “where the big action was,” he later told The Post.

After fulfilling Army service in 1961, Elder joined the United Golfers Association (UGA), the sport’s equivalent of baseball’s Negro Leagues. It was sometimes called “The Peanut Tour” because of its small winners’ purses, usually $500.

During one torrid stretch in the early 1960s, Elder won 21 out of 23 UGA tournaments. At one tournament in Washington in 1963, Elder met his first wife, Rose Harper, an excellent golfer who became his business manager.

Elder’s path to the Masters began in 1961, when the PGA of America, then the governing body for golf, eliminated its “Caucasians-only” rule. Charlie Sifford, who died in 2015, became the first African American golfer on the PGA tour.

In 1967, Elder earned a spot on the tour, finishing ninth out of 122 players at the PGA’s qualifying school. Eschewing financial backing, he put up the $10,000 minimum required to enter the tour. He had accumulated the money from his UGA victories, giving private lessons at public courses in Washington, where he had settled, and by hustling.

“Several Caucasians offered me financial help,” he told The Post in 1969, “but I couldn’t see giving anybody a portion of the money I won. That’s why it took me so long to get started. I wanted to save up enough money myself.”

He gained national recognition in 1968, when he tied Jack Nicklaus in the American Golf Classic in Akron, Ohio, after 72 holes, only to lose on the fifth hole of a sudden death playoff. Nevertheless, he raked in more than $12,000 for his performance, and began to market Lee Elder golf clubs and balls and appear in commercials.

At the time, Elder said he faced tremendous pressures and indignities as one of a small number of Black golf professionals on the PGA Tour. Racial epithets were yelled from the galleries, he received unsigned death threats and harassing phone calls. He was turned away from hotels in the South despite confirmed reservations and sometimes he was forced to change clothes in the parking lot because he was not allowed in the clubhouse.

He recalled that his friend, Jackie Robinson, who broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947, advised him not to retaliate. “It’s easy to get in trouble and hard to get out of trouble,” Elder said Robinson told him.

In 1971, Elder accepted an invitation from his friend, White South African-born golf star Gary Player, to participate in the South African PGA championship in Johannesburg. The country was still under apartheid rule, and U.S. civil rights leaders urged Elder not to go.

But he and Player achieved a remarkable diplomatic breakthrough, persuading government officials to open the tournament to all races — making it one of the first integrated sports events in the country. In addition, Elder obtained permission for him and his wife to travel freely across the country. Later that year, Elder won the Nigerian Open.

In 1972, Augusta National, the private club that runs the Masters, changed its qualifying rules to extend an automatic invitation to any player who won on the PGA Tour. Two years later, Elder won the 1974 Monsanto Open in Pensacola, Fla., sinking an 18-foot putt on the fourth hole of a sudden death playoff to defeat Peter Oosterhuis.

His victory on the PGA Tour earned him a spot in the 1975 Masters, one of golf’s four major championships. Two earlier African American golfers, Pete Brown in 1964 and Sifford in 1967 and 1969, had won PGA Tour events but were denied an invitation to the Masters because of rules in place at the time.

In the run-up to the 1975 Masters, Elder said the threats against his life intensified to the point where he rented two houses in Augusta, one under an assumed name.

“Even when the tournament started, I’d get notes, calls, but I was determined not to let it bother me, and it really never did,” he told The Post. “It was unfortunate, but I put it out of my mind. I was there for one reason, to play golf and do the best I could.”

Elder drew a huge crowd when he teed off in the first round of the Masters on April 10, 1975. After he birdied the third hole to go 1-under par, he saw his name on a leaderboard. It didn’t last. He shot 74 the first day and 78 in the second round and did not make the cut for the tournament’s final two rounds.

Elder qualified to play in five more Masters and had his best finish in 1979, when he tied for 17th. In April, the 86-year-old Elder made an emotional return to Augusta as one of three honorary starters of the 2021 tournament, along with Player and Jack Nicklaus.

“One of the things that is quite sad,” Player, a three-time Masters champion, told Sports Illustrated in 2008, “is that Americans don’t know how significant it was what Lee did. Many athletes are given great rewards for their athletic prowess. I think Lee Elder did something that beats the prowess of an athlete.”

Robert Lee Elder was born July 14, 1934, in Dallas, the youngest of 10 siblings. His father, a coal-truck driver, was killed during Army service in Europe during World War II. His mother died months later, and he was shuttled among various relatives, eventually winding up with family in Los Angeles.

He began caddying at 12 on public courses, making $1 a round while also honing his skills during the hours set aside for caddies to play. “It was something to do rather than running the streets,” he told The Post.

Elder lived in Washington for 25 years while married to his first wife, and they managed the historically Black Langston Golf Course for several years. After their divorce, Elder moved to South Florida.

Survivors include his second wife, the former Sharon Anderson, whom he married in 1995.

During his years on the PGA Tour, Elder captured four tournaments, the 1974 Monsanto Open, the 1976 Houston Open, the 1978 Greater Milwaukee Open and the 1978 Westchester Classic. He surpassed $1 million in career earnings. In 1979, he became the first African American golfer to qualify for the U.S. Ryder Cup team, matching teams from the United States and Europe.

Elder left the PGA Tour in 1984 and joined the senior Champions Tour for players 50 and older. He won eight senior tournaments and continued to compete occasionally into his 70s. In 1987, he suffered a heart attack while playing in the Machado Classic in Key Biscayne, Fla. A year later, he won the tournament, posting a 65 in the final round.

After he retiring from tournament golf, Elder occasionally traveled to Augusta for the Masters. He was there April 13, 1997, when 21-year-old Tiger Woods began his final round.

Woods won by a record 12 strokes to become the first African American Masters champion.

“I wasn’t the pioneer,” Woods told reporters afterward. “Charlie Sifford, Lee Elder and Ted Rhodes played that role. I thank them.”

Before Woods’s historic victory, Elder stood on a hill overlooking the first tee. As he watched Woods make his way through the crowd, tears welled in Elder’s eyes.

“If Tiger Woods wins here, it might have more potential than Jackie Robinson’s break into baseball,” he told this Post reporter, who was standing next to him. “No one will turn their head when a Black man walks to the first tee.”