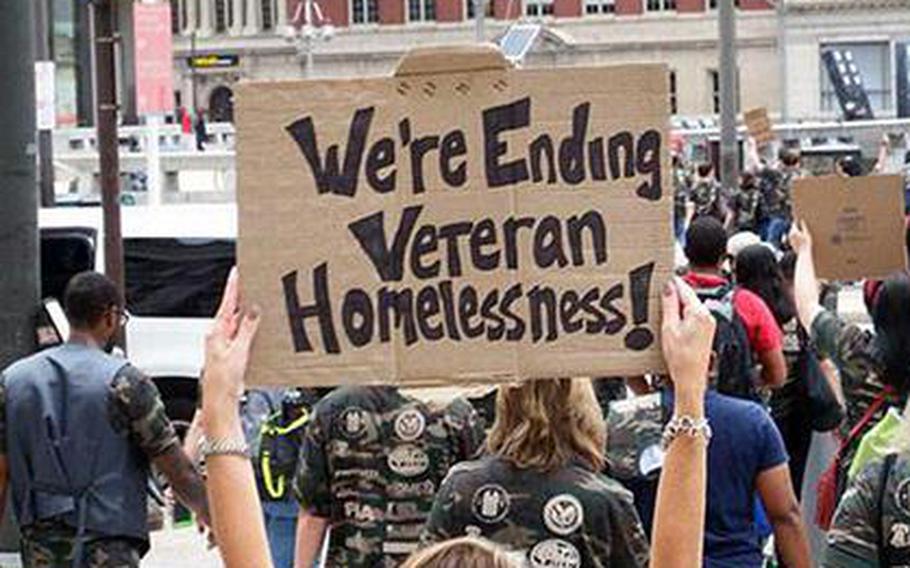

The National Coalition for Homeless Veterans is objecting to an executive order by President Donald Trump’s administration directing greater use of involuntary civil commitments to forcibly move homeless people into institutions. The order will disproportionately affect veterans, who are twice as likely to experience homelessness compared to the general population, according to the coalition. (VA.gov)

WASHINGTON — The National Coalition for Homeless Veterans is objecting to an executive order by President Donald Trump that directs state and local officials to forcibly move people living on the streets into long-term “institutional settings.”

The coalition — a national network of nonprofits that provides veterans housing and other assistance — is protesting a July 24 executive order by Trump titled “Ending Crime and Disorder on America’s Streets.”

The order connects homelessness to increased crime and seeks to end “vagrancy” and “violent attacks” by strengthening enforcement actions that include compulsory stays for homeless individuals at hospitals and other treatment facilities.

Kathryn Monet, chief executive officer of the coalition, said the order will disproportionately affect veterans, who are nearly twice as likely to experience homelessness compared to the general population.

Involuntary commitment is a legal process for placing people in institutional settings such as hospitals and treatment centers without their agreement or consent, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Anna Kelly, White House deputy press secretary, said Tuesday that the executive order will help people “struggling with addiction or mental health challenges get the help they need.”

The executive order states the “overwhelming majority of [homeless] individuals are addicted to drugs, have a mental health condition, or both.”

But Monet said her organization has found homelessness among veterans often is driven by rising housing costs and a shortage of units that are affordable to rent or own.

“Even if every homeless veteran were institutionalized, our country lacks the affordable housing capacity to support them post-institutionalization,” she said.

Housing subsidies combined with job training programs and counseling services are evidence-based solutions that are more effective and less costly than “forced institutionalization,” Monet said.

“The executive order’s emphasis on involuntary hospitalization and stripping away due process protections is deeply troubling,” she said. “Historically, mass institutionalization has caused harm and failed to provide long-term solutions.”

More than 32,000 veterans are homeless on any given night, according to the 2024 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, a one-night census led by the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Annette Johnson, a 63-year-old disabled Army veteran, said her chronic problems with homelessness are connected to a lack of finances. Johnson, who collects disability and Social Security, said she lacks the money to cover the upfront application fee and down payment for an apartment. (Annette Johnson)

Annette Johnson, a 63-year-old disabled Army veteran in Baltimore, is one of them.

“I’ve been homeless since last October. The VA told me to go to a homeless shelter, but I don’t feel safe there,” said Johnson, who has a 100% disability rating from the Department of Veterans Affairs from back, neck and kidney injuries connected to military service. “I sleep on buses and trains. I do what I can to survive.”

The executive order states “shifting homeless individuals into long-term institutional settings for humane treatment through the appropriate use of civil commitment will restore public order.”

But Johnson, a former staff sergeant who served from 1980 to 1993 with deployments to Korea and Germany, said: “I don’t pose a safety issue to anyone. People are not homeless because they want to be. That does not make sense.”

Johnson moved out of subsidized housing she previously qualified for in 2024 because it was infested with rodents.

She said her VA disability compensation plus monthly Social Security checks cover short-term hotel stays, food and storage for her belongings. But the money runs out before the end of each month, and she does not have the resources to make a deposit on an apartment.

Johnson also said she has never used illegal drugs.

Veterans homelessness has dropped by 50% since 2010, according to the VA. The vast majority of veterans who received housing assistance in 2024 remained in their homes, according to VA figures.

The coalition expressed concern the executive order will lead to an increase in civil commitments for individuals with mental illness or substance use disorders when the organization advocates expanding treatment in the community.

Monet also criticized the order for tying federal grant funding to a willingness by nonprofits to employ “punitive measures to address homelessness.”

The executive order directs HUD and the Health and Human Services Department to end “housing first” policies that “fail to promote self-sufficiency.”

The order also directs the attorney general to “ensure that homeless individuals arrested for federal crimes are evaluated … to determine whether they are sexually dangerous persons and certified accordingly for civil commitment.”

But Trump’s executive order will protect homeless women and children from being housed with sex offenders, Kelly said.

“The executive order will incredibly alienate this population of veterans. We need to be addressing the root causes of homelessness,” said Raymond Carville, public affairs manager with Veterans Inc., a not-for-profit agency providing veterans in Montana, North Dakota and across New England with housing assistance and other services.

Many former service members the agency serves are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder — a mental health condition that is a response to witnessing terrifying events, he said.

Carville said his agency encounters many veterans who delay asking for help until they’ve lost jobs and housing. He said he is encouraging veterans to step forward and seek assistance before they are in “dire circumstances.”

“It is incumbent on veterans to reach out to agencies that can advocate for them,” he said. “We find a lot of veterans are afraid to step forward. They’re not used to asking for help.”

Johnson, who is estranged from her adult daughter, said she experiences the effects of PTSD related to military service.

“I have a lot of problems with depression,” she said. “I’m in survival mode. I’m just trying to stay alive.”

Rather than stay outdoors on the streets during the day, Johnson said she often rides a metro bus through downtown Baltimore because it’s free, safe and has air-conditioning. She said she looked at an apartment Monday afternoon, but she did not have the money to cover upfront costs.

“I just need help with the application fee and down payment,” Johnson said. “I have the first month’s rent, but it will put me in a hole for the rest of the month.”