Larry Liss in 1966, sitting in a Huey helicopter with two orphans in South Vietnam. During the Vietnam War, Liss flew more than 650 combat missions. One of those missions resulted in Liss and co-pilot Tom Baca rescuing 87 friendly forces from a surrounding North Vietnamese force of about 650 fighters. (Larry Liss)

Army pilot Capt. Larry Liss arrived at the Green Beret outpost at Cau Song Be, Vietnam, in an unarmed Huey — the only helicopter on site at the time — when all hell broke loose on May 14, 1967.

Some 7 miles away, about 650 North Vietnamese were poised to overrun a small special operations outpost, where roughly 100 South Vietnamese soldiers and a small group of Green Berets were positioned.

What came next involved Liss and co-pilot Tom Baca flying six times into a small, contested area, in a frenzied rescue operation that helped save 87 troops with the help of a second Huey.

Their heroics were comparable to the exploits that led to last week’s ceremony at the White House, where President Joe Biden pinned the Medal of Honor on Vietnam War pilot Larry Taylor, according to people with firsthand knowledge of the events.

“I think the number of people (Liss and Baca) rescued exceeds that of any other helicopter mission I know of,” said Jack Swickard, an Army pilot who was part of the rescue mission at Cau Song Be on the second helicopter, which accounted for nearly half of the 87 saved.

Now, the story of the daring rescue at Cau Song Be is sparking calls for the Medal of Honor for some of those involved in a forgotten mission.

“We need someone (in Washington) to champion this effort,” said Larry Liss’ brother, Arthur, who has compiled a 2,100-page history of the rescue that incorporates affidavits and flight logs as well as admissions from leaders at the time who say the pilots and several others weren’t given their due.

For more than a decade, a push has been underway to get the Distinguished Flying Crosses awarded to Liss and Baca upgraded. Liss is now 82, and Baca died in 2020.

In the citations for those medals, much was left out of the account, including the size of the surrounding enemy force. Also unmentioned was the 87 friendly forces saved on the six rescue flights aboard a helicopter used for VIP transportation rather than combat.

On two of those flights, Liss stepped out of the Huey and used his rifle to fight the enemy while friendly South Vietnamese troops known as Civilian Irregular Defense Forces raced toward the aircraft.

“When you look at the facts, this is a Medal of Honor case,” Arthur Liss said, adding that the matter has been mired in Army human resources bureaucracy for years.

Numerous lawmakers have written to the Army on behalf of Lary Liss for Medal of Honor consideration, going back to 2009 when former Pennsylvania U.S. Rep. Joe Sestak first got involved in the case.

At the time, Sestak said in a letter that he “wholeheartedly” supported a Medal of Honor recommendation for Liss and that he was coordinating with the Army.

But by 2011, Sestak was out of office. Since then, it’s been a revolving door of lawmakers making cursory inquiries but not taking the matter up with enough vigor to break through Army bureaucracy, Arthur Liss said.

Last week’s awarding of the Medal of Honor to Taylor, an Army pilot who made a treacherous flight to rescue four soldiers from a surrounding enemy force of 100, could add weight to the argument that Liss, Baca and Swickard should be considered for similar honors, given the similarity of their missions.

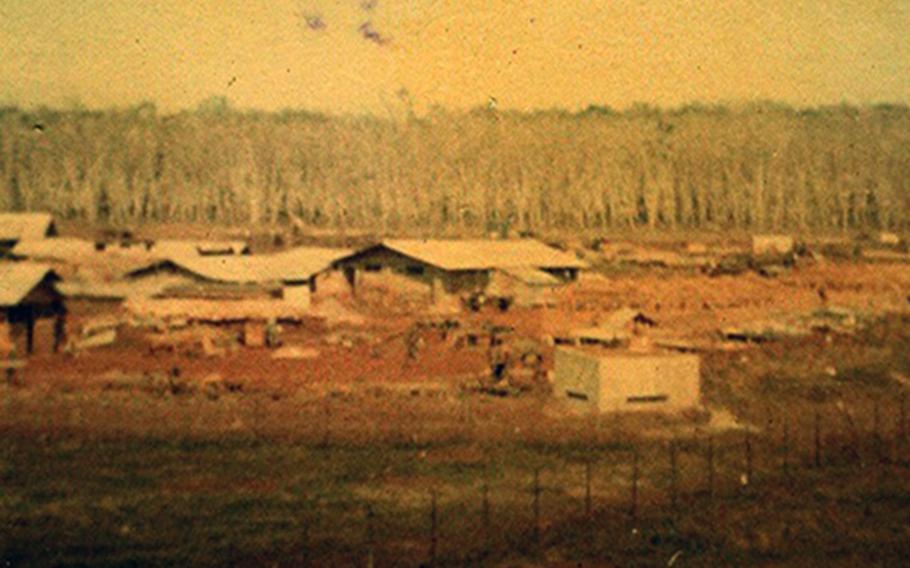

Cau Song Be was a Special Forces camp that was used by Green Berets during the Vietnam War. On May 14, 1967, Warrant Officer Tom Baca and Capt. Larry Liss flew an unarmed Huey to rescue troops from an ambush that involved around 650 North Vietnamese. (Jack Swickard)

The rescue

Liss and Baca arrived at Cau Song Be at about 3:30 p.m. on a Sunday with the staff chaplain, who was visiting a small special operations outpost. It was supposed to be an easy mission.

But a Green Beret captain in charge of the camp approached the pilots to request help with a medical evacuation for troops getting overrun.

“(Liss and Baca) immediately volunteered, even though I noticed that their aircraft was an unarmed, VIP aircraft. There was no hesitation,” the former captain, retired Lt. Col. Wallace Johnson, wrote in a 2009 affidavit that detailed the events of the day.

In a separate 2009 affidavit, Baca said that when the pilots arrived, the area looked “impenetrable in all directions as far as we could see.”

They had to lower their Huey through a jungle of tree branches and bamboo, weed-whacking the vegetation with their rotors to create a landing zone. The maneuver nearly rendered the aircraft unable to fly because of the damage it inflicted.

“That was an unheard-of maneuver for a UH-1 aircraft, but doing it five additional times makes it really unique,” Johnson said in the affidavit.

About 15 minutes before Baca and Liss arrived, another helicopter had attempted a similar landing but damaged its tail rotor blade and had to withdraw to a safer position, Johnson said.

When Baca and Liss touched down, a firefight already was underway, with casualties inflicted close to their helicopter.

Once aboard the Huey, Johnson and another special operations adviser helped load the injured onto the aircraft before making their escape.

On subsequent flights, the danger increased.

Liss and Baca cut through more bamboo with their rotors to get closer to friendly troops as the perimeter shrank, with enemy forces some 50 yards away.

“I witnessed that CAPT Liss, in total disregard for his own well-being and safety exited the aircraft on the fifth and sixth landings with his personal weapons to assist in rallying the troops left on the ground,” Baca wrote. “He was totally exposed to small arms fire on both of these courageous initiatives. They were outside of his normal duties of a pilot, but showed bravery beyond the call of duty.”

Added Swickard in a statement to Stars and Stripes: “Larry left the cockpit to push survivors into the helicopter and covered them with fire from his rifle.”

Larry Liss said the deteriorating situation demanded that he act as the South Vietnamese struggled to hold off the enemy force.

“(Enemy forces) were really close, and I just saw this mess unfolding,” Liss said Monday by phone. “So I got out of the aircraft and I helped them create the perimeter and I engaged where I had to.”

The surrounding area was a plantation, which likely made it hard for the enemy to line up a clear shot on Liss.

“I think the only thing that saved us was there were too many bamboo trees,” he said.

Swickard, on a separate Huey, said the fighting was so intense that South Vietnamese soldiers boarding his aircraft were getting shot inside it.

“The bodies of the soldiers killed on board the helicopter were thrown off by the other CIDG members to make room for more of the living,” Swickard, 80, said. Liss and Baca encountered the same.

On the final flight out, the helicopter was so overloaded that the rescued were clinging to the outside of it.

In Johnson’s 2009 affidavit, he recommended that Liss, Baca and Swickard receive the Medal of Honor for their efforts.

Swickard said Johnson’s recommendation was turned down. In the years since, his focus has been on advocating for Liss and Baca.

During the ambush, six South Vietnamese soldiers and two U.S. special operations soldiers were reported killed.

If not for the “heroic efforts of the helicopter pilots and their crews,” the entire team “would have been killed or captured,” said Johnson, who died in 2018.

Baca also wrote that had details of the rescue been known by higher headquarters at the time, a recommendation of Medal of Honor would have been likely for Liss.

Fog of war

Part of what’s kept the rescue at Cau Song Be in obscurity is the fact that officials at the time never got the details down in writing.

John Green, who was an operations officer of the II Field Forces Flight Detachment, acknowledged as much years later.

In a letter to the Army’s awards and decorations branch dated Sept. 23, 2010, Green said he was angry at Liss then and chewed him out because he believed that Liss had unnecessarily risked the life of Baca, whose tour in Vietnam was ending in a matter of days.

“I regret deeply my own actions in this matter. I felt protective of my aircrews. It was that very sense of protectiveness that caused me to overreact that day,” Green wrote. “Unfortunately, it has contributed to both officers receiving less recognition than they might otherwise have gotten.”

Green said he and others in the chain of command “were remiss in our duty to investigate that action on 14 May and to properly honor these men and their crew chief for their heroism.”

The lack of communication at the time also meant that their commander in Vietnam, Lt. Gen. Fred Weyand, was never fully apprised of Liss and Baca’s heroics until many years later.

Weyand, who went on to become the chief of staff of the Army, wrote in a July 2009 letter that Liss, Baca and the crew of the other Huey involved in the rescue “displayed uncommon valor.”

“Review of reports indicates that if it were not for the extraordinary heroic actions of the flight crew who made repeated extractions, the friendly forces would have suffered severe casualties,” a then-retired Weyand wrote to Maj. Gen. Galen Jackman, who was the Army’s chief legislative liaison at the time.

Weyand recommended that the Army review the case to determine what higher awards were in order.

So far, the Army Board of Corrections of Military Records has declined Medal of Honor consideration for Liss four times based on various technicalities, his brother said.

The board also wrongly characterized Baca’s affidavit as a “depiction” rather than an eyewitness account, a distinction that has complicated the approval process, Arthur Liss said.

Still, there’s been some recent movement in the case.

After numerous rejections, the Army’s awards and decorations office in May issued an advisory opinion saying that Larry Liss met the minimum standards for the Silver Star and referred the matter to the Army Board of Corrections for Military Records.

The board, which can accept or reject the advisory opinion, has yet to rule on the matter.

While a Silver Star would be an upgrade, Arthur Liss said it still falls short of recognizing the level of valor his brother demonstrated on May 14, 1967.

Larry Liss said he’s tried to stay out of his brother’s way when it comes to advocating.

“I don’t speak up and I don’t push because I’ve discovered early on (that) if I was fighting and speaking up for Tom and Jack, people would say ‘Well, that’s self-serving,’ ” he said.

What’s needed is “somebody with no ax to grind to call it like a really good referee,” Larry Liss said. “Because this has not had a good umpire.”