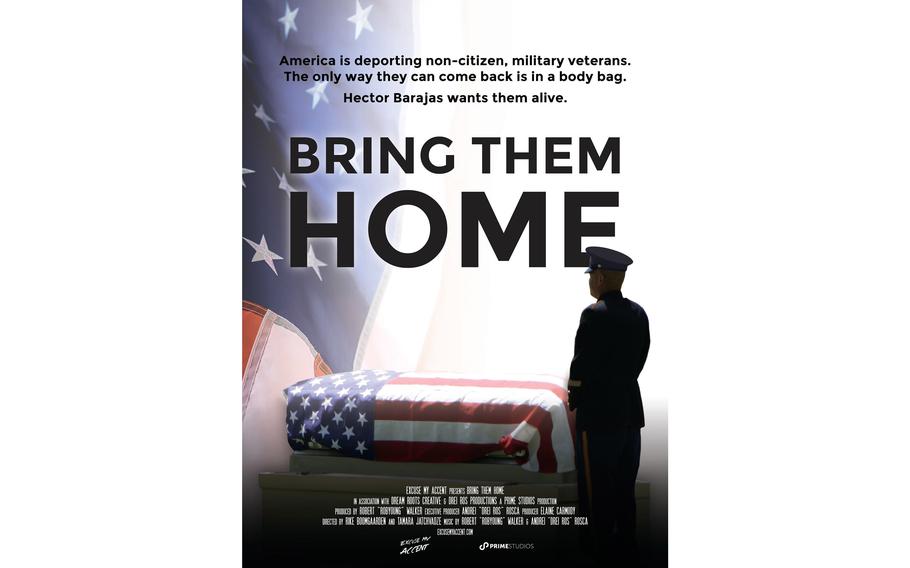

The plight of deported veterans is the subject of filmmaker Rob Walker’s documentary, “Bring Them Home.” (Bring Them Home Film/Facebook)

(Tribune News Service) — For some foreign-born troops, bureaucratic battles replace the real ones they fought in Iraq and Afghanistan. Instead of losing a limb, these service members lose their ability to stay in the United States. They are deported veterans — men and women who voluntarily joined the U.S. military, served honorably and then were deported when they tripped legal landmines.

Their plight is the subject of filmmaker Rob Walker's documentary, "Bring Them Home," which will screen Saturday at The Grand Cinema in Tacoma, Wash. A panel discussion will follow.

Foreigners fighting for America have been part of the country's history since its founding. Yet, joining the military does not guarantee citizenship. Service in the military only makes a person eligible to apply for citizenship, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Some 35,000 non-citizens serve in the U.S. military and 8,000 join every year, according to military.com. The 30-minute film interviews veterans who served with American forces but without the benefit of having U.S. citizenship and were later sent back to their countries of origin after an offense, no matter how minor.

Tacoma born

Walker grew up in Tacoma and found himself working in the entertainment industry after high school. He is a music artist by the name of Rob Young and CEO of a media and design company. He splits his time between Washington and California.

He fell into the cause of deported veterans by chance. In 2020, he released the single, "Excuse my Accent," and its music video with Romanian-born rapper Drei Ros. The video featured deported veterans.

"I realized how expansive that conversation is, especially when we talk about cultures and connectivity and what it means to have an accent in the USA," Walker said.

'Bring Them Home'

The more Walker researched deported veterans, the more shocked he became over the issue. He made contact with Hector Barajas, a deported veteran who was born in Mexico but grew up in Los Angeles from age 7. Barajas runs a support group for deported veterans and appears in the documentary.

It is hard to know how many veterans have been deported, Walker said, as there is no official tally. The issue ignites conversations about nationality, immigration, patriotism, loyalty and other topics.

"It's a window to talk about a larger dialogue of us as human beings and how we see each other," Walker said. "What does it mean to be American?"

Politics

The issue of deported veterans comes as a surprise to most of the people he meets, Walker said. He was recently on a California college campus and approached a military recruiter.

"He called me a liar," Walker said. "He actually got a little upset and I said, 'No, I did a documentary.' He had no idea. I talk to veterans. They have no clue."

In political rhetoric, veterans and immigrants can be portrayed as polar opposites. One group is heralded as the American ideal while the other is portrayed as villains — sometimes by the same politicians. When the two issues overlap, as they do with deported veterans, the complexity does not fit neatly into a political narrative.

Most politicians do not want to talk about deported veterans, Walker said. But some, such as Illinois Sen. Tammy Duckworth, California Sen. Alex Padilla and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, are supportive. Sanders, who said he wants to return deported veterans to the United States, appears in Walker's documentary.

Daniel Torres

Daniel Torres was born 3 miles south of the U.S. border in Tijuana, Mexico. Those 3 miles came back to haunt him when he became an adult.

Torres, 37, came to the United States at 13.

"I was DACA before there was DACA," he said, referring to Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which creates a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants who entered the United States as children.

It was after high school when a childhood friend-turned-military recruiter pitched the idea of becoming a Marine to Torres. He enlisted even though he was undocumented.

Three years in and after a promotion to Lance Corporal and a tour in Iraq in 2009, he was recommended to join an intelligence unit. Background checks for intel personnel are more rigorous than the general military, and it was discovered that Torres was a Mexican citizen.

Honorable discharge

After an honorable discharge, Torres tried to join the French Foreign Legion, but a war-related hearing injury disqualified him. He soon found himself back in Tijuana in 2011. In 2017, he earned a law degree in Mexico.

During law school, Torres met Barajas, who runs Deported Veterans Support House.

"It gave me a community of veterans to connect with, to talk with," Torres said. "It was difficult being a veteran and transition to civilian life while being deported."

Torres suffers from PTSD and was suicidal after his departure from the military and the United States. He eventually became an advocate for people like him. He speaks about the subject and works on documentaries such as "Bring Them Home."

Torres' case was picked up by the ACLU, and he was eventually granted U.S. citizenship. He now lives in Salt Lake City.

"I feel like what happened was because I was making so much noise," he said of his citizenship.

A simple mistake

The same mistake or misdemeanor that would result in a fine or a short jail stay for a U.S. citizen could be a life-altering event for a non-citizen.

"They get deported for, like, possession of marijuana, failing to pay child support, writing a bad check, driving with an expired license," Torres said. "There was a guy who failed to appear in court because he was deployed."

Immigration law, Torres said, is unforgiving.

"It doesn't care what kind of person you've been your entire life," he said. "It doesn't even care if you're a veteran. It's looking for an excuse to get rid of people."

Automatic citizenship

Torres acknowledges that some veterans are deported for serious crimes, including murder. He still thinks a four-year enlistment and an honorable discharge should qualify any service member for automatic U.S. citizenship.

Complicating the situation every four or eight years is a new administration, which produces its own policies. What is needed, Torres and Walker said, is an act of Congress.

"Now, we're talking about immigration reform," Torres said. "And the moment you say immigration reform, people's minds shut off, and politicians want nothing to do with that."

Beyond Mexico

While Mexicans and other Latin American citizens make up the bulk of deportees, Walker's film points out that deportees come from Africa, Europe, Asia, Canada and other parts of the world.

The film has won prizes at several film festivals, and Walker said he will continue his advocacy work around the issue.

"I'm a pit bull; my jaw is locked," he said. "My goal is to take this, God willing, to the highest stage that I possibly can."

Ultimately, Walker said, the issue is a lens into the heart of America.

"What is the soul of our nation if we could do this?" Walker said of deported veterans who risked their health and lives to defend the United States. "What's more American than willing to die for it?"

The common thread that all of deported veterans he has met, Walker said, is a love for the U.S.

Torres, who is coming to Tacoma for the screening, frames it as an issue of justice.

"I've never committed a crime," Torres said. "I've never joined ISIS. I've never done anything against the United States. But I was born three miles away. Now my veteran service doesn't mean anything."

(c)2023 The News Tribune

Visit TheNewsTribune.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.