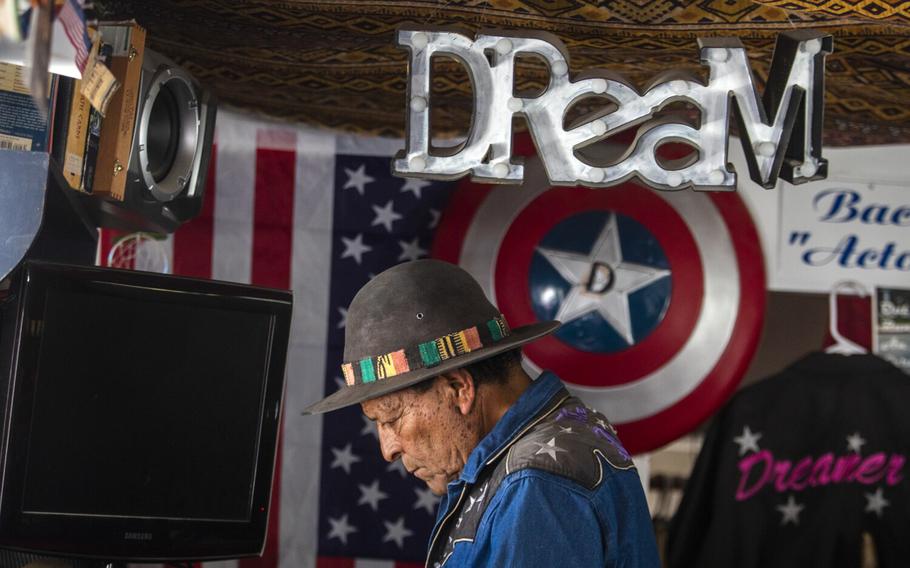

Barber Tony Bravo, known as “Dreamer,” is seen inside the Barber Shop on the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs campus on June 15, 2022, in Los Angeles, California. (Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

(Tribune News Service) — The almost 80-year-old man who cuts hair on the streets of West Los Angeles is not your typical barber.

Most of his clients are homeless, and many are military veterans; the price is negotiable and can be paid in food (preferably fresh fruit); and nobody with empty pockets is turned away.

“Ring Man!” the barber called out the other day to a U.S. Navy veteran who often pays for his haircuts with costume jewelry.

Ring Man — 32-year-old Omar Herrera — handed over a clutch of rings and a few dollars as payment for a trim, and the barber immediately handed the cash over to a man who pulled up in a dented Nissan Sentra.

The driver, 78-year-old Vietnam veteran Wilbur Thornton, said he needed gas money and would pay it back soon, as he always does.

“He listens, he understands, he never puts a person down,” Thornton said. “And he gives free haircuts.”

The barber is Antonio Bravo Esparza, known to some as Tony Bravo. But most people refer to him by his preferred name, which is stitched onto the back of his western-style blue shirt: “The Dreamer.”

“I’m an Apache medicine man,” said the Dreamer, who served six years in the National Guard, has a soft spot for vets and throws an apron patterned with a U.S. flag over them when he cuts hair.

A Dreamer, to hear Tony Bravo explain it, embraces ancestral Native American values. He thinks of himself as a shaman and a shape-shifter on a pilgrimage of healing. His particular dream is that, given what he calls the most divisive times since the Vietnam war, human connections built around good deeds, mutual respect, objectivity and respect can create a wave of positive energy.

“I think it’s time for us to realize we’re in the same storm and different boats,” said the Dreamer, who thinks it might help if we paddled together.

When Herrera paid for his haircut partially in rings, the Dreamer handed one to my colleague Francine Orr and one to me. Once we had slipped them on, he said, the three of us were bonded, like power rangers whose mission is to beam positive energy into the universe.

“Flexibility, magic, love,” the Dreamer said. “Let’s have fun and not take ourselves so seriously.”

The Dreamer was featured in a 2011 Times story by Martha Groves and Annie Cusack. He had begun his haircutting career in upscale Westside parlors, and some of his old customers still seek him out. But he took a detour many years ago, parking his trailer on the West L.A. Veterans Affairs campus to serve veterans and anyone else who wandered in. When the pandemic hit, the doors of his “ Freedom Barber Shop” were locked, but that didn’t throw the Dreamer off his stride.

A reader named Alex Nicol saw him cutting hair in a parking lot near Ohio Avenue and Sepulveda Boulevard and was curious enough to stop and say hello. Nicol enjoyed chatting with Dreamer and suggested that I would, too.

The Dreamer is not one to answer a straight question with a straight answer. A typical response winds through his thoughts on mystery, the moon and the metaphysical, all of which intrigue him more than the literal world. He shared some of his background but insisted that those details say less about him than does his daily quest to commune, in the moment, with the people he encounters.

I can tell you that he’s homeless, or at least sort of. As the 2011 story pointed out, the Dreamer has a piece of property and relatives in Arizona, but even when he visits there regularly, traveling by train, he’s not comfortable sleeping indoors.

“I don’t do good inside,” he told me. “The sky and the stars and the trees are my roof.”

That springs in part from his childhood. He and his father left their home in Corona, Calif., and traveled the state as farmworkers, fished dinner out of rivers and lakes and stared up at the stars from their campsites. The young Dreamer picked walnuts in Chico. Prunes in Colusa. Cotton in Corcoran.

“It was beautiful,” he said of his childhood, which he recalls not as back-breaking labor but as working in the service of an essential need.

“If you offered me a $2-million house in Brentwood, I would say keep it,” said the Dreamer, who told me he sleeps on the street, in an upright position and facing east. That’s the direction of the next event, he said, the next opportunity, the next dawn.

Many of the homeless people he knows are suffering, said the Dreamer, and he wishes there were more help and housing for them, particularly those with mental illness and those scarred by combat. He is there with and for those travelers, he said, and likes to tell them that despite their circumstances, they are all rich.

“I have a different value system, you might say,” the Dreamer told me. Success and happiness are based on conventional but misguided notions, he said, which is why the sign he hangs at his haircut sites says “ Dreamer’s School of Unlearning. Apply within.”

“I tell my vets that if you have a car and get on the road and cross a bridge that costs millions to produce, that bridge is yours and you can use it 24/7, anytime you want. They don’t think like that, but I do. I’m grateful,” said the Dreamer.

I drove him to his shuttered trailer, where he sometimes finds clients waiting for a haircut and tells them where they can find him off-campus. Two friends of his — both vets — were hanging out at the trailer.

One, a homeless man named Paul, said the Dreamer is good with the shears. The other, Keystone, who served with the Army in the Middle East and suffered traumatic brain injury, was despondent about a contentious family drama and knew the Dreamer would help him through it.

“He’s a poet; he’s a shaman,” Keystone said. “Every day, he is fully in the day. He’s got a ranch he could go to, but he chooses to be here. To be of service.”

The Dreamer, who has a favorite playlist, fired up his stereo. He loves “Over the Rainbow” and “Impossible Dream,” Johnny Cash gets a lot of air time, and, at the moment, Patsy Cline was singing “Crazy.”

Keystone laid out the specifics of his sorrow and confessed, fighting tears, that he had “gone back to the weed.” The Dreamer told him not to let the drug be the “it” that he thinks he needs and to find a power object — something of profound meaning to both him and the relative with whom he was at odds — and let it be a healing force.

“There are good days ahead,” the Dreamer told Keystone.

We headed back to the Dreamer’s spot on Ohio, where a client with a service-related mental health disability was waiting for a haircut. The Dreamer set up his Old Spice cologne, gel product and scissors on a wobbly stool, fired up his small generator, plugged in his shears and went to work.

Before long, Keystone showed up with his guitar and an amp and played his heart out before taking his turn in the barber’s chair — a castaway office recliner on wheels — and getting a haircut under a eucalyptus tree.

The Dreamer kept his eye on his work, carefully running his shears over Keystone’s scalp. He said that among the people he knows and cares about — the homeless, the addled, the wounded, and even the well-heeled — everyone is just trying to find their way home.

©2022 Los Angeles Times.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.