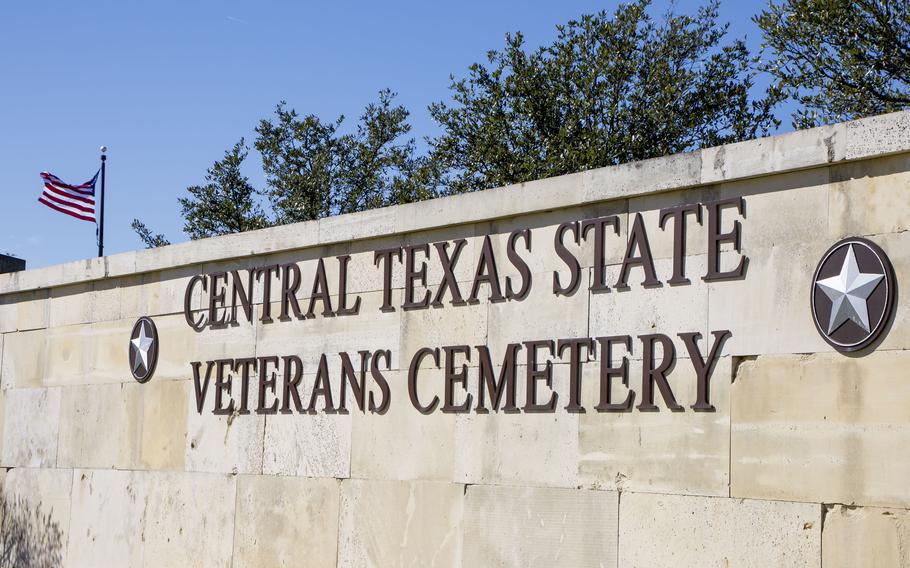

The Central Texas State Veterans Cemetery in Killeen, Texas, as seen here in 2019, is one of four veterans cemeteries run by the state. Officials began discussions in October of adding new cemeteries to the system, which has sparked a debate on the best way to fund the growth. (Texas General Land Office)

Texas officials are looking to expand the state’s veteran cemetery system to meet its large veteran population, but some officials questioned whether doing so will come at the expense of services for living veterans.

The issue prompted the first public meeting of the Texas State Veterans Cemeteries Committee in more than 15 years and has led to the resignation of the cemetery program’s top official, the reassignment of a state agency’s chief investment officer, and triggered numerous letters between state officials about comments that described the cemeteries as “money-losing” programs.

It’s an emotional, complicated issue that state officials will need to spend some time on, said state Sen. Charles Perry, a Lubbock-based Republican, who would like to see one of the next veterans cemeteries built in his city.

The Central Texas State Veterans Cemetery in Killeen, Texas, as seen here in 2019, is one of four veterans cemeteries run by the state. Texas buries about 2,000 people each year in the cemeteries and is discussing whether to add new locations to meet population growth. (Texas General Land Office)

Overall, the population in Texas grew by nearly 4 million people during the last decade. About 1.5 million veterans live in the state — a number that has held steady as younger veterans make Texas their home. The post 9/11 veteran population in the state has grown by more than 118,000 in 10 years, while the number of World War II and Korean War veterans declined by about 140,000.

Officials participating in the meeting agreed the state could benefit from increased veterans cemetery space, but they have to decide how to manage the growth.

Building two new cemeteries, one in Lubbock and another possibly in the town of Tyler, was the plan under discussion at the recent meeting of the cemeteries committee. Lubbock, which is in the northernmost portion of the state — known as the Texas Panhandle — lacks a nearby option to offer veterans. Tyler, which is in the eastern region of the state, has seen its veteran population grow in recent the years.

“We've got to prepare and look ahead 20 years, and make sure there's capacity to meet those needs,” Perry said. “We just need to have an honest conversation about [whether] that is a state responsibility or is that a continuation of robbing Peter to pay Paul out of veteran programs that exists today? Or do we have enough [burial space]?”

The Department of Veterans Affairs runs 155 national cemeteries across the country, according to the department. States can set up their own cemeteries based on federal guidelines as a way to augment the system, and can apply for funding from the Veterans Cemetery Grant Program.

George P. Bush, commissioner of the Texas General Land Office, left, and retired Air Force Mater Sgt. Eric Brown, former deputy director of Texas State Veterans Cemeteries, attend the burial of an unaccompanied veteran in 2019 at the Central Texas State Veterans Cemetery in Killeen, Texas. (Texas General Land Office)

There are 119 state, territorial and tribal veterans cemeteries that have received those VA grants in the past 40 years, according to the VA.

In locations where 80,000 or more veterans are without reasonable access to a national cemetery or VA grant-funded cemetery, the VA’s National Cemetery Administration will establish a new national cemetery. Reasonable access is defined as living within 75 miles of an already established cemetery, either federal or state.

As of this month, the VA calculated nearly 94% of veterans living in the U.S. have reasonable access to a burial option. The strategic goal of the administration is to offer reasonable access to 95% of veterans.

The Texas legislature first authorized state-run cemeteries for veterans in 2001, allocating $7 million yearly from the Veterans Land Board for up to seven cemeteries. Since then, four have opened. There are also five federal cemeteries in the state, one of which is only open for cremated remains. A sixth federal cemetery is closed.

During the Oct. 29 meeting of the cemeteries committee, Rusty Martin, the chief investment officer for the General Land Office, said the four existing cemeteries each cost about $2.2 million annually to operate. Even with outside funding that comes primarily from VA grants and reimbursements, each one loses about $1.34 million per year.

If all things remain the same, he expects the program to reach the $7 million threshold for state funds by 2028. Additional money for the cemeteries would have to come from other veterans programs such as nursing homes and a home-loan program, both of which generate their own funds, he said.

“I’m a money guy. I’m not comfortable putting any kind of money into money-losing programs,” Martin said during the meeting. “It doesn’t make sense to me. But there are political considerations here and other considerations.”

Retired Air Force Master Sgt. Eric Brown, then the deputy director of Texas State Veterans Cemeteries, said the comments were a public expression of the disrespect he’s seen toward cemeteries within the Veterans Land Board since he became the top official in 2013. The comments led him to resign from the position, effective Nov. 30.

“[The cemeteries] should be there first to honor our veterans and say thank you,” Brown said. “That’s the way I perceive it. I wish the agency would perceive it that way.”

Martin’s comments also prompted some state lawmakers to write letters of concern to George P. Bush, the chairman of the Veterans Land Board and commissioner of its higher agency, the General Land Office.

“These disrespectful remarks have resulted in a severe loss of confidence among many Texas veterans in the [General Land Office’s] future management of the Texas State Veterans Cemeteries,” wrote state Sen. Kelly Hancock, a Republican from North Richland Hills and chairman of the Senate Veterans Affairs and Border Security Committee.

Bush responded with a letter to Hancock that Martin was relieved of duties related to the Veterans Land Board, but he remains on staff with the General Land Office.

“As a former naval intelligence officer who deployed to Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom, I firmly believe that his remarks were disrespectful and insulting to anyone who has put on the uniform to serve our great nation,” Bush wrote.

The General Land Office declined requests for interviews.

State Sen. Juan “Chuy” Hinojosa, a Democrat from Corpus Christi, wrote a letter to Bush that called for Hancock’s committee and Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick to study funding of the cemeteries and consider moving the program to a different state agency, the Texas Veterans Commission.

Outside of state funding and VA grant money, state-run cemeteries also get federal reimbursement for burials, which rose in October from $807 to $828 per burial. The reimbursement doesn’t fully cover the $3,400 each burial costs the state, Martin said during the October meeting.

The VA does not reimburse for spouse burials and Texas does not charge for them. Some states, such as California, do charge for them.

California’s legislature also allocates money each year, most recently about $1.68 million, for its three state-run cemeteries, one of which is a small cemetery that serves a veterans nursing home. The state also accepts contributions from private donors and local communities that support the cemeteries, said Michael Magee, assistant deputy secretary of the Veterans Services Division at the California Department of Veterans Affairs. The plan in California is to provide the cemeteries as a benefit to veterans and their families, he said.

“It’s a great place for veterans to gather to commemorate Memorial Day, to celebrate Veterans Day, and to honor the people who are no longer with them,” Magee said. “The state of California has contributed and supported the funds that we’ve needed to keep it operational, in part for those reasons.”

Texas and California have similar veteran populations, 1.5 million and 1.8 million, respectively, according to officials from each state. Texas, however, buries about 2,000 people a year at its state cemeteries whereas California does slightly more than 1,000.

Perry, the Texas senator who is advocating to have a new cemetery in Lubbock, said his district is now served by a state cemetery in Abilene, which has plenty of room to grow. But many Lubbock-area veterans don’t like idea of their loved ones having to travel more than 320 miles round trip to their gravesite.

He said he also understands the need for fiscal responsibility when it comes to other veterans programs, and he is working with the VA to determine whether the city can qualify for federal designation, particularly because it could draw in veterans living in eastern New Mexico, southern Colorado and western Oklahoma.

“I can understand the veterans appeal for it, but I'll be truthful, I've got just as many veterans that would say, ‘Well, you know, we're about living,’” Perry said. “Is it more important for me to be living on these things than it is to be worried about my final resting place?”