Dick Higgins smiles while talking with a visitor during his 100th birthday celebration in Bend on Saturday, July 24, 2021. Higgins served as a Navy radio operator in a PBY Catalina amphibious aircraft when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. (Ryan Brennecke/Bulletin)

BEND, Oregon — The room in the quiet house on Harvard Place in Bend, Oregon, is full of memories, but when Dick Higgins needs help bringing the oldest ones into focus, he'll often grab a magnifying glass.

At 100, Higgins won’t let himself forget how he survived the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor. He has surrounded himself with handwritten notes, books and black-and-white photographs at a table in the home he shares with his granddaughter and her family.

His hand shakes as he holds the magnifying glass to a logbook he used as a 20-year-old Navy radio operator in Pearl Harbor. He turns his attention to a nearby stack of history books about the attack full of his written descriptions in the margins. One note reminds Higgins of how he sought cover under a plane filled with 1,500 gallons of fuel. The plane could have easily exploded.

“Not a good place to be at the time!” Higgins wrote.

Higgins has made it a point to honor a promise that Pearl Harbor survivors hold close to their hearts: to remember what happened that day and those who died in the hail of death delivered by Japanese warplanes on an otherwise quiet Sunday morning in Hawaii.

Dick Higgins, who at 100 is the oldest living Pearl Harbor survivor in Central Oregon, looks through his flight logs at his desk on Oct. 7, 2021. Higgins served as a Navy radio operator in a PBY Catalina amphibious aircraft when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. (Ryan Brennecke/The Bulletin)

The blue ballcap Higgins wears nearly every day helps with that.

As long as his family can remember, Higgins has worn the cap that identifies his naval squadron, VP-22, and is embroidered with the words "Pearl Harbor Survivor." There are seven pins on the cap, including one that reads, "Remember Pearl Harbor."

People notice the ballcap when they see Higgins in a grocery store, at a restaurant or on the streets of Bend. He always stops to share his story, just as he did 15 years ago when he was president of the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association chapter in Orange County, California. Back then, he often spoke to schoolchildren about the attack.

The last time Higgins was at Pearl Harbor was on Dec. 7, 2016, when there were three known survivors living in Bend. Now he is the only one.

The other survivor in Central Oregon is 99-year-old Marvin Emmarson, of Sisters, who served in the Navy during the attack.

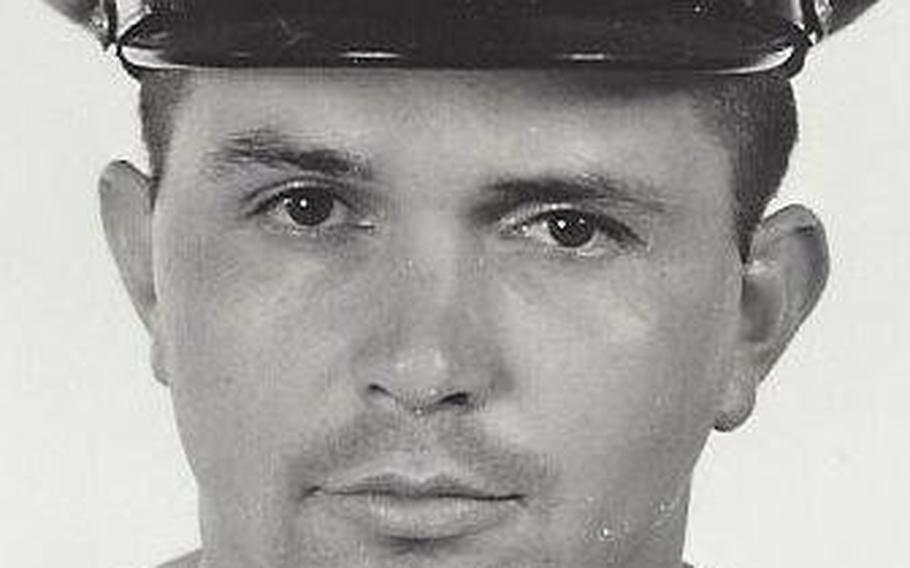

Dick Higgins, top row; center, at the U.S. Naval Training Station in Great Lakes, Illinois, on Dec. 23, 1939. (Submitted photo/ The Bulletin)

Ever since his trip in 2016, Higgins has vowed to attend Tuesday’s ceremony honoring the 80th anniversary of the attack. The great-grandfather isn’t planning another trip. His family knows he has longevity in his veins, but the reality is that if Higgins lives to see the 85th anniversary, he will be too frail to travel.

For the centenarian to stand on the edge of the harbor this week, at the place where his life was cemented into history, is a moment that will never happen again.

“I want to reminisce and see the beach down there again,” Higgins said. “I’ll try to figure the details of that day and honor the people who lost their lives.”

Honoring the legacy

Going back to Pearl Harbor honors the dead who never got a chance to live the kind of full life survivors did. In the years after the attack, Higgins pursued a career in radio engineering, got married and raised two children. In the 1960s, he briefly ran a Winchell's Donut House in Southern California. Today, he has two grandchildren and four great-grandchildren, who are all accompanying him on the trip back.

All the men in Higgins’ barracks survived the attack. But Higgins still witnessed the destruction that killed 2,390 Americans.

Higgins served in a 130-member squadron and was assigned to a flight crew as a second class radioman on Ford Island in the center of Pearl Harbor. He often flew on missions in PBY Catalina amphibious aircraft.

The devastation sticks with the survivors. Some have even returned after death, their ashes interred by divers on the sunken hull of the battleship USS Arizona, which lies on the harbor bottom below a gleaming white memorial. More than 900 Arizona crewmen remain entombed in the ship.

Emily Pruett, a spokesperson for the Pearl Harbor National Memorial, whose great-uncle survived the attack, said the survivors are living links to that era.

“It’s so meaningful for everybody to have that tangible access to the past," Pruett said.

Their motivation to return inspired the National Park Service to host an 80th anniversary event, despite the complications created by the COVID-19 pandemic, Pruett said. Last year’s anniversary was done virtually due to the virus.

Pruett expects Tuesday’s ceremony to host between 150 to 250 World War II veterans, including about a 40 Pearl Harbor survivors. Their presence is especially meaningful because for many, it will be their last visit. The youngest Pearl Harbor survivors today are 98.

“Their willingness to travel speaks to their generation's character,” Pruett said.

Their attendance is impressive for another reason. No more than 75 survivors are thought to be alive, said Kathleen Farley, the California chapter president with Sons and Daughters of Pearl Harbor Survivors.

Farley said the first ceremony at Pearl Harbor was held in 1966 to mark the 25th anniversary of the attack. Before then, the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association formed in 1958 and held a reunion Dec. 7, 1960, at Disneyland. The association disbanded in 2011, due to the survivors getting older, leaving Sons and Daughters chapters to keep the memories alive. Today, there are 13 chapters in 12 states.

Farley, a retired high school teacher from Concord, California, has worked with the Sons and Daughters group for more than 30 years. She has dedicated her life to preserving the legacy of those who fought and died that day. Her father, John. J. Farley, was aboard the USS California during the attack. He survived for one reason.

“He knew how to swim,” she said.

Farley went back to Pearl Harbor with her father for the 50th anniversary in 1991, and again every five years until her father's death in 2007. She has gone back every year since to honor him.

The site of the attack is sacred to the survivors and the need to return is powerful, Farley said.

“I have heard from many survivors that they will return to Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7 to be the voice of the survivors that didn't make it,” Farley said.

Dick Higgins in World War II. (Submitted photo/ The Bulletin)

For most of the last 80 years, the Pearl Harbor survivors have returned to mark each anniversary. They joined diplomats, admirals and presidents. They brought memories to share and children — and later, grandchildren — to share them with.

The 50th anniversary drew more than 2,000 survivors,cq who were feted with a parade through the streets of Waikiki. Time has thinned their ranks, however.

By 2016, an estimated 300 survivors returned for the 75th anniversary. About 15 arrived in 2018 and a dozen the following year.

Their annual pilgrimage has been called a last hurrah for several decades, but it may finally be true in 2021.

Higgins has returned to Pearl Harbor several times.

His first trip back was in 1991 with his late wife, Winnie Ruth Higgins, to mark the 50th anniversary of the attack.

He went back five years later, and he was there for the 60th anniversary, less than three months after the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. About 800 Pearl Harbor Survivors returned that year and the presence of an estimated 600 New Yorkers — police, firefighters and their families — linked both surprise attacks.

"When the planes went into the towers I was really ticked off," Higgins recalled. "Very familiar feeling to Pearl Harbor.”

He would return three more times — in 2006, 2011 and 2016.

When he traveled to Hawaii to mark the 65th anniversary in 2006, he wanted to see where he was stationed on Ford Island. It can be reached by bridge but is not open to civilian traffic.

Higgins and other survivors were invited to the island for a tour of the newly opened Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum. He went with his granddaughter's husband, Ryan Norton.

The two strayed away from the tour to visit the site of a hangar used by Higgins' squadron that was destroyed in the attack. But they wandered too far from the tour and missed the bus back to their hotel.

At that moment, an officer stepped out of a nearby building, thinking Higgins and Norton were trespassing.

“He looks at grandpa and says, ‘Stay there,’” said Norton, a 46-year-old loan officer in Bend. “He went back inside and we thought we were in trouble.”

Instead, having realized Higgins was a Pearl Harbor survivor, the officer brought six sailors to meet him. The sailors were no older than Higgins was when he was serving in Hawaii. They gathered around to hear Higgins' story.

“It was really so cool to see these guys listen and grandpa describing exactly what happened,” Norton said. “They stayed with us for an hour.”

After talking with the sailors, the officer drove Higgins and Norton to their hotel.

Every trip back to Pearl Harbor makes Higgins feel like royalty. On other trips, Higgins was stopped for photographs with people, has signed autographs and met strangers who offered to pay for his dinner.

He accepts the attention, but only as much as his humble nature will allow. After all, he and the other survivors didn’t choose their role in history.

“It felt nice that they were honoring us,” Higgins recalled. “We were just doing what we were supposed to be doing.”

From the Dust Bowl to Waikiki

Higgins smiles whenever he calls himself a survivor. And he's not always referring to Pearl Harbor. He's been at the forefront of other major moments in American History. In the 1930s, he overcame a childhood in the Dust Bowl and Great Depression. Last year, he beat COVID-19 when he was 99.

And three weeks before the trip, Higgins was briefly hospitalized in Bend, suffering from pneumonia symptoms.

He was born July 24, 1921, near the small town of Mangum, Oklahoma. His parents, Ernest and Lula Elizabeth Higgins, were farmers who grew cotton, corn, and grain and often struggled to make ends meet.

“We were po’folks,” Higgins likes to say in his Sooner accent.

One of Higgins’ childhood memories is seeing the large plumes of dust blanket his town.

“The dust came rolling in on the ground,” Higgins said. “Street lights came on around noontime because it was so dark.”

Higgins went to high school in a class of 13 students. After school, he worked in a hat factory and dreamed of a better life. In December 1939, Higgins enlisted in the Navy and was assigned to an air station in San Diego, where he saw the ocean for the first time. He was 18.

Higgins couldn’t believe his luck when he was assigned to Pearl Harbor in October 1940. Living in Honolulu was like visiting a remote paradise. He spent his free time bodysurfing off the shore of Waikiki, laying on the beach to get a suntan and flirting with girls at a local malt shop. He even tried surfing once.

“Those things would turn you every way but loose,” Higgins said of riding a surfboard. “I tried that and I couldn't do it. I was not a good swimmer.”

Higgins made friends with the men in his squadron, and they would stay out late exploring the island. But they had to be back by midnight. They called it their "Cinderella liberty."

One evening, Higgins and a friend took out a boat in the harbor and invited some girls to join them.

They had no idea a war loomed over the horizon.

“We had some good times out there,” Higgins said. “The Japanese messed it up.”

'It keeps him alive'

The attack on Pearl Harbor began when Japanese planes dropped out of the skies above Oahu at 7:55 a.m., the same moment every year that the base falls silent and those gathered there pause to reflect on the fury unleashed that day.

For nearly two hours that Sunday, Japanese bombers and torpedo planes delivered blow after blow, and not only at Pearl Harbor, but across Oahu. When they had finished, boils of fire and black smoke rose over the harbor, and the U.S. Pacific fleet had been severely crippled.

Higgins woke up that morning to the sound of Japanese warplanes overhead. He was ordered to stay in his barracks during the first wave of the attack. Higgins’ commanders then sent his squadron to the airfield to salvage as many airplanes as possible.

“We finally got down to the hangar and started moving planes around to get them away from the ones that were on fire,” Higgins said. “When they explode, they throw gas over the others.”

Higgins was covered in ash and oil as he moved planes on the airfield. He worked nonstop and didn’t return to his barracks for three days.

He was assigned to saving planes rather than people, so he was spared the trauma of watching his colleagues die. Other survivors are left with the unsettling memories of seeing friends disappear into the water.

Still, Higgins experienced carnage he could not have imagined.

“They witnessed it all day,” said Angela Norton, Higgins' granddaughter. “He was out there working and trying to get everything back to somewhat normal for them to be able to get out and start a war.”

Norton, 44, is her grandfather’s primary caregiver since he moved in with her family in 2015. She watches over him along with her 7-year-old son, Josiah, and 2-year-old daughter, Noelle. She listens to her grandfather's stories and takes videos of him for his Instagram account, where he shares the history of his life.

In recent years, on the anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack, Norton leads her grandfather to the frozen shore of the Deschutes River for the annual ceremony at Brooks Park in Bend. Norton has made it her mission to fulfill Higgins' dream of returning for the 80th anniversary.

“It keeps him alive, having this goal,” Norton said. “It’s all he talks about.”

At some point on Tuesday, perhaps after the ceremony at Kilo Pier, Higgins and his family will make the short walk to the shore of Pearl Harbor and embrace the memory one more time.

It is tradition to throw a flower lei into the water near the USS Arizona Memorial. Half of the dead at Pearl Harbor were on the battleship.

Higgins plans to reach the waterfront and honor the promise he has kept for eight decades.

He’ll look out at the harbor and then gently toss the lei.