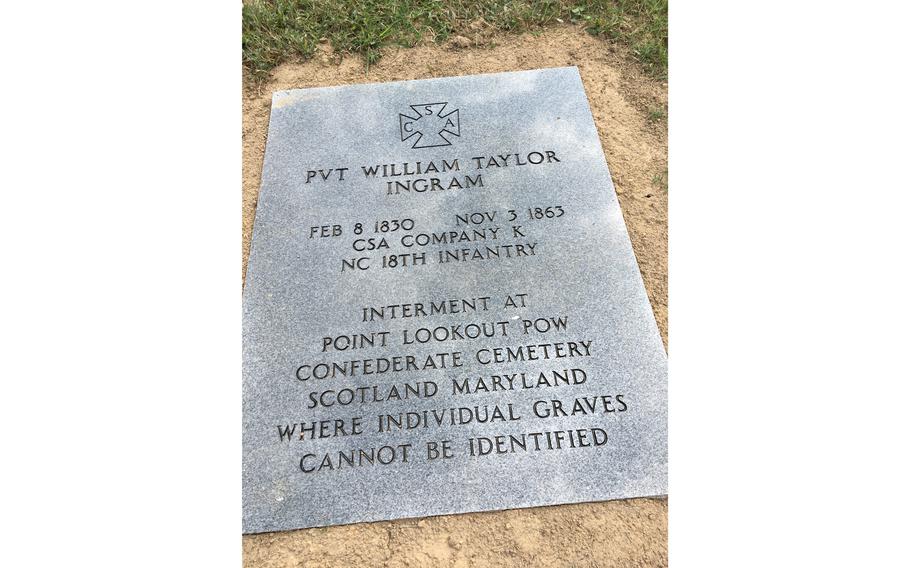

Gary Holland at the granite marker in Gastonia’s Hollywood Cemetery, which marks the service of his great-great-great grandfather William Taylor Ingram. (Bill Poteat, Gaston Gazette/TNS)

GASTONIA, N.C. (Tribune News Service) — Gary Holland never knew his great-great-great-grandfather William Ingram, of course.

Ingram died in 1863 and Holland was not born until more than eight decades later.

But Holland feels a special bond with his ancestor who fought at the Battle of Gettysburg with the Army of Northern Virginia, was taken prisoner there, and died in a federal prisoner of war camp four months later.

The ties are of blood.

And the ties are of experience.

Both men took up arms because they believed it was their duty to do so.

Both men endured the horrors of combat, knowing they could die at any moment.

But one man came home to his wife, to his son, and to a future that was bright with promise.

The other was buried in a mass grave, unmarked and unremembered.

And that, Holland believes, is unacceptable. He believes it is his duty now to make sure the legacy and sacrifice of Pvt. William Taylor Ingram are never forgotten.

Growing up in Dallas before Marine service

Now 73, Holland grew up in Dallas and remembers an idyllic childhood there, playing a variety of sports with his youthful friend and neighbor, Gazette columnist Michael McMahan.

After graduating from Gaston High School in 1965, he enlisted in the Marine Corps. Following a tour of duty in the Mediterranean Sea, he returned briefly to the United States and was then off to South Vietnam.

1968.

The year of the Tet Offensive.

The year that nearly 17,000 young Americans were killed in combat.

Holland came very close to being one of that number.

"I was a machine gunner, in the northern part of the country near the demilitarized zone," Holland said. "We were setting up for an ambush. Grenades were thrown right among us. I took a lot of shrapnel."

The wounds meant Holland's days on the front lines were over. But his exit ticket came at a horrible cost. He spent the next six months of his life in a Philadelphia hospital. Recovery was slow and painful.

After returning to Gaston County with his wife Sandra and their young son, Holland earned a degree in mechanical engineering from UNC Charlotte and spent years designing machines for the still-flourishing textile industry.

When that industry began to wane, he shifted gears and became an industrial curriculum developer and instructor for South Carolina, working to make sure workers had the skills necessary to staff new and developing industries.

Ironically, it was the death of his mother that spurred Holland's interest in his family's history and, in particular, the legacy of his great-great-great-grandfather.

The marker honoring William Ingram in Gastonia's Hollywood Cemetery. (Bill Poteat, Gaston Gazette/TNS)

Seeking out a lost legacy

"When my mom died, we discovered that she had left notes about her family history," Holland said. "It was when we were going through those notes that I first read about Pvt. William Taylor Ingram."

Ingram was born in Iredell County in 1830. In 1862, he enlisted in the Confederate military and was assigned to Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. When he headed north, he left behind his wife, Caroline, and three children under the age of 5.

He would never see them again.

Within weeks after enlistment, he was fighting in some of the most memorable battles of the Civil War - Antietam, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. He survived them all.

And then came Gettysburg.

Judged by many historians to be the pivotal turning point of the Civil War, the battle raged for three days. Ingram was in the North Carolina 18th Infantry Regiment, Company K.

On the battle's final day, Lee ordered a frontal assault on the entrenched line of the Union forces. Ingram's unit made it all the way to their objective, Cemetery Ridge, where the Confederates were overwhelmed by the Union's superior numbers.

Cut off and unable to retreat, Ingram was captured.

As already noted, four months later, he was dead.

Holland's research revealed that his great-great-great-grandfather's fate after capture was a tragic one.

After being moved around several times, Ingram ended up at Point Lookout Prison Camp in Scotland, Md., on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay.

Written accounts, from both Confederate and Union sources, paint a horrible picture of life at the camp. Little or no food, inadequate shelter, barbaric medical care.

Pleas from the camp commander for more food, more supplies, even a decent amount of firewood fell on deaf ears.

His body wracked by dysentery, Ingram died in the camp hospital on Nov. 3, 1863.

Stirring a passion

What happened after Ingram's death has fueled Holland's passion to commemorate his ancestor's life and service.

Ingram was buried in a mass grave outside the prison. No headstone. No marker. No nothing.

The shifting shoreline of the bay prompted the bodies to be moved twice, the last time in 1910.

"Local workers were paid by the number of bodies," Holland said, "and that basically came down to counting skulls. Decency gave way to expediency, and skulls were separated from the rest of the remains, commingled, and placed in mass graves."

When Holland began his research, he had hoped to be able to bring Ingram's body home to Gaston County for a proper burial.

That was not to be, so Holland decided instead to place a granite marker at the Ingram family burial plot in Gastonia's Hollywood Cemetery.

The inscription on the marker is a simple one:

"Pvt. William Taylor Ingram, Feb. 8 1830 - Nov. 3 1863, CSA Company K, NC 18th Infantry. Interment at Point Lookout POW Confederate Cemetery, Scotland, Maryland. Where Individual Graves Cannot Be Identified."

A spirit comes home

As Holland talked about his own life and experiences, even his wounding in Vietnam and the long recovery afterward, his manner has been light, his eyes smiling.

But when asked why he felt it so important to honor his great-great-great grandfather, he grows silent for a moment, tears well in his eyes, and when he does speak, his voice is halting and fraught with emotion.

"He needs to be honored," Holland said. "His courage, his sense of duty, his sacrifice. There needs to be a record. There needs to be a monument. There needs to be a place where his descendants can go and remember their rich heritage."

Later, Holland and a Gazette reporter go to Hollywood Cemetery together to visit the granite marker.

It is a fine mid-October morning. The autumn sun still warm. The sky overhead an endless blue. The sort of morning that a farmer born in Iredell County nearly two centuries ago would have treasured.

No, the earthly remains of William Taylor Ingram do not rest beneath that granite marker and indeed never will.

But for Holland, and all the members of his family, Ingram's spirit has finally come home.

©2021 www.gastongazette.com.

Visit gastongazette.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.