Charles McAllister poses in his World War I uniform in this undated photo. (Beverly Dillon)

When Beverly Dillon’s home phone rang on a late summer evening in 2019, she ignored it. She didn’t recognize the number and assumed it was a pesky marketing call to her home in a small Montana town near Glacier National Park.

But as the caller began leaving a message on her old-fashioned answering machine — mentioning the surnames Vincent and McAllister — Dillon raced to pick up the phone.

“Yes! I was a Vincent before I was a Dillon, and my grandmother's maiden name was McAllister,” the self-described “genealogy nut” recalled saying. “I nearly jumped out of my skin I was so excited.”

On the other end of the line was Jay Silverstein, a forensic anthropologist who said he believed he had identified the remains of Pfc. Charles McAllister, her great uncle who died in battle during World War I.

Silverstein had just retired from the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency in Hawaii, the U.S. government’s official agency tasked with bringing home the remains of the nation’s missing war dead, but this was the one case he could not bear to leave unresolved. The remains had been stored at the agency’s Hawaii lab for 15 years.

Dillon, now 80, and her son, Sean, submitted DNA samples to the Department of Defense DNA Registry in August 2019, for which she received a letter of receipt a few weeks later. It was the last contact she had from the government concerning the samples, she said. More than a year later, the case has gone nowhere.

Silverstein, who now teaches forensic anthropology in Russia, is frustrated with what he regards as DPAA’s foot-dragging on a case he insists could have — should have — been completed years ago.

Silverstein’s criticism of how the Defense Department operates its accounting effort is nothing new. He had been among the internal whistleblowers who complained of failings of the agency’s predecessor, the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command, sending a memo, for example, to the agency’s commander in 2012 describing shortcomings in efforts to recover World War II remains on Tarawa.

His complaints were among those that led the Defense Department to reorganize the effort to account for the nation’s missing warfighters by creating the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, or DPAA, in 2015.

In a civil lawsuit he filed that same year in U.S. District Court in Hawaii, Silverstein alleged that certain agency personnel had retaliated against him over his complaints and other matters, a case he lost by jury trial in 2017.

Nevertheless, when Silverstein was leaving the agency last year, he was presented the Meritorious Civilian Service Award by Rear Adm. Jon Kreitz, then deputy director of DPAA.

‘Not authorized by statute’

DPAA Director Kelly McKeague outlined the agency’s position on the World War I case in a Nov. 23 letter to U.S. Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., in response to the lawmaker’s query.

The agency, McKeague wrote, is not authorized by statute to account for remains in conflicts before World War II.

“At the same time, acknowledging Dr. Silverstein’s efforts, DPAA is coordinating with the [Defense Department] components to hopefully facilitate an identification,” he wrote. More DNA samples are required from “other known family members,” but the U.S. Army Casualty and Mortuary Affairs Operation Center had not yet located them, he wrote.

Silverstein contends that DPAA has an overwhelming amount of physical, circumstantial and historical evidence indicating the remains are those of Charles McAllister. He also argues that the agency has an obligation to account for pre-World War II remains that come into its possession — as has been done in past cases.

“Once these remains are accessioned into the laboratory, in my opinion, the agency has accepted responsibility to treat them with the dignity, respect, diligence, and honor due their sacrifice for our nation,” Silverstein said in a Dec. 5 email to Stars and Stripes in response to the McKeague letter. “I am frankly befuddled by the dancing around of scientific and bureaucratic excuses for years, rather than vigorously seeking a way to do what is a moral imperative and what should be an honorable tribute to someone lost as [missing in action] while fighting for our nation.”

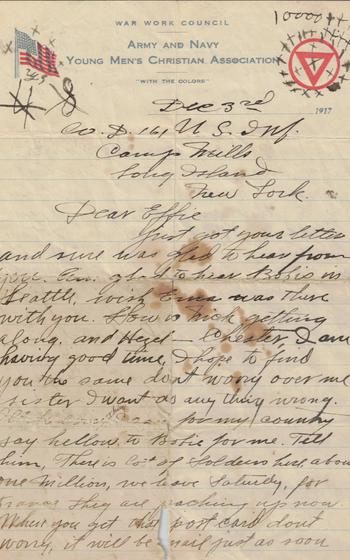

The first page of a letter written by Charles McAllister to his sister Effie dated Dec. 3, 1917, sent before he shipped out from New York for France, where he died in July 1918 during the Second Battle of the Marne. (Beverly Dillon)

‘Unsolvable’

McAllister’s remains have been stored in a box in DPAA’s Hawaii laboratory since 2004 after being exhumed, along with a second set of remains, from a construction site by archaeologists in France the year before.

In 2005, Silverstein successfully identified that second set of remains as being those of Pvt. Francis Lupo, a case resolved in part because a wallet embossed with Lupo’s name had been found among the artifacts.

The first set of remains defied quick identification. Silverstein completed his analysis and passed the case to a historian at the lab, which at that time was part of the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command, or JPAC.

“He said it was unsolvable,” Silverstein said during an interview via Skype this fall.

In response to a query about the case from Stars and Stripes, DPAA spokeswoman Maj. Leah Ganoni said in an emailed statement that Silverstein’s recollection was accurate.

Silverstein’s attention over the following years turned to recovery efforts in North Korea, Vietnam and Tarawa, but as America approached the 100th anniversary of its entry into World War I in April 2017, he pulled that unsolved case out for another look.

“The case always bothered me because I felt there was enough information there to follow up on,” he said.

He scoured the available clues, including uniform insignia that indicated the soldier had been a member of the Washington National Guard. He retrieved and reviewed a history of that Guard unit.

He used geographic information system mapping to reconstruct the Second Battle of the Marne, which coincided with the site on which the archaeologists had found the remains. For cross reference, he searched the American Battle Monuments Commission website for soldiers missing from World War I.

He narrowed the search by considering where and when Lupo had been killed, surmising that their deaths had commonality. He came up with a list of 30 missing service members fitting the general criteria for the remains — but considered only five to be real possibilities.

At this point in his career, Silverstein was heading up a geographical information systems unit for DPAA, and he could not get official authorization to work the case, he said. His requests for records from the National Archives for the men on the list were repeatedly rejected by the contractors working for DPAA at the archives.

Ganoni said in the statement that Silverstein’s recollection of these events is accurate.

“In 2017, Mr. Silverstein’s supervisors did not want him to work on this incident using government time because DPAA is not authorized under relevant laws and DPAA's charter to work on WWI cases,” she said.

Narrowing the list

Silverstein said he spent his own time and money retrieving National Archives records in an effort to identify the remains. Volunteers helped with genealogical work to track down descendants of the five service members on his list.

McAllister and Pvt. Rudolph Ulrich possessed the closest physical matches to the remains. Silverstein crossed Ulrich off the list when a DNA sample from one of his descendants did not match.

A dental record for McAllister stored at the National Archives set him apart from others on the short list: his first and second molars from both sides of the lower jaw were missing.

“He had very distinct tooth extractions that matched up to the skeleton perfectly,” Silverstein said. “I don’t recall seeing that particular dental pattern previously.”

The height and build between the remains and records also “matched perfectly,” he said.

But McKeague said in his letter that “there are a number of individuals who could be associated with the remains.” That necessitates the use of nuclear DNA testing, as opposed to the mitochondrial DNA testing used on samples submitted by Dillon and her son, he said.

The genetic code in mitochondrial DNA is passed from mothers to children in almost unaltered form through generations. But nuclear DNA possesses roughly 3.3 billion more base pairs than mitochondrial DNA, making it a vastly more unique identifier.

Ganoni, the DPAA spokeswoman, told Stars and Stripes that the mitochondrial sequence found in the samples from Dillon and her son are “fairly common and not unique to make an individual identification.”

Silverstein said a process of elimination has winnowed the list down to only McAllister, making further DNA testing unnecessary.

“The statistical coincidence of the biological profile, the dental record, and the circumstances of loss of soldiers from the Washington State National Guard, 2nd Regiment, Company D, makes it highly improbable and next to impossible that these remains could belong to someone else,” Silverstein wrote in the Dec. 5 email. “Certainly, the cumulative evidence in this case is consistent with the highest level of legal and forensic precedent for accepting the identification of an MIA.”

An innocent letter

The case took on greater meaning to Silverstein after his initial hourlong conversation with Dillon last year.

On Dillon’s family room wall hangs a framed letter that her great uncle sent to his sister Effie — Dillon’s grandmother — on Dec. 3, 1917, from New York before shipping out for France. She read it to Silverstein during that first call.

“I’ll do everything I can for my country,” wrote McAllister, who enlisted at 23 while living in the Seattle area. He concluded, “From boy gone away to war, remember me in the sweet by and bye and I’ll come home when the war is over.”

“Poor Jay was almost in tears by the time I finished reading the letter,” Dillon said. “It was just such an innocent letter.”

As of early December, Dillon had not been contacted by anyone from the Defense Department seeking leads on family members or additional DNA samples, she said.

Silverstein said in his Dec. 5 email that if DPAA has determined it is unable to “fulfill the responsibility our nation owes to Pfc McAllister, it is incumbent upon them to transfer the remains to another military mortuary authority as expeditiously, transparently, and respectfully as possible.”

“I don't think the family is concerned about what government authority oversees the identification of Charles McAllister,” Silverstein said. “They do, however, think that his remains sitting in a cardboard box for 16 years in Hawaii is simply unacceptable and that further hesitation or indecision on how to treat the remains is intolerable.”