Taps plays during the Aug. 2, 2025, funeral of 1st Lt. Charles “Woody” McCook in Georgetown, Texas. The pilot died in combat in World War II on Aug. 3, 1943. (Rose L. Thayer/Stars and Stripes)

GEORGETOWN, Texas — First Lt. Charles “Woody” McCook made a decision in his final moments on Aug. 3, 1943, that would save the lives of two crewmembers aboard his B-25C Mitchell bomber.

The aircraft was flying over Burma and McCook — a 23-year-old pilot — managed to pull the bullet-riddled aircraft from its dive at 50 feet back to about 1,000 feet, allowing the men to parachute out before it crashed.

McCook and three other men died on the bomber that day, though their remains would not be collected for another four years and more than 80 would pass before McCook’s remains would be identified and returned home to Texas.

First Lt. Coleman Anderson of Fort Hood presents Diane Benefiel with a folded American flag during the Aug. 2, 2025, funeral of her uncle, 1st Lt. Charles “Woody” McCook in Georgetown, Texas. The pilot died in combat in World War II on Aug. 3, 1943. (Rose L. Thayer/Stars and Stripes)

Allin Still on Saturday recounted the story of McCook’s heroism before more than 100 people gathered under a sweltering sun to bury the pilot at the Independent Order of Odd Fellows Cemetery where his parents and brother were laid to rest years before him.

“May we all live our lives with the same sense of duty and honor,” said Still, who is a member of VFW Post 8587.

Diane Benefiel, 75, the oldest living relative of McCook, accepted numerous honors from the area’s veterans community and the standard folded flag presented by soldiers of the 1st Cavalry Division from nearby Fort Hood. As a hearse delivered McCook’s remains to the downtown cemetery, dozens of people lined the streets waving American flags.

People watch a flyover following the funeral of 1st Lt. Charles “Woody” McCook, who died in combat in World War II on Aug. 3, 1943. His remains were identified in April 2025 and he was buried in Georgetown, Texas, on Aug. 2, 2025. (Rose L. Thayer/Stars and Stripes)

“It’s all so very moving,” said Benefiel, who lives in Houston.

Her father John was the youngest of the three McCook boys — all of whom were sent to World War II, though only two made it home.

“I felt bad for my grandmother. She had three sons who were in the military,” Benefiel said. “That was nerve-wracking in itself.”

Back in Georgetown, the boys were known as the “Flying McCooks” because they all learned to fly. However, Benefiel said her father’s eyesight wasn’t great, so he went into the Navy instead.

Charles McCook, who commissioned Feb. 3, 1942, entered the service five months later after graduating from Southwestern University in Georgetown. Soon the local media reported he had been sent to China.

Soldiers from Fort Hood prepare to fold an American flag draped on the coffin of 1st Lt. Charles “Woody” McCook, who died in combat in World War II on Aug. 3, 1943. He was buried Aug. 2, 2025, in Georgetown, Texas. ( Rose L. Thayer/Stars and Stripes)

McCook was a member of the 22nd Bombardment Squadron, 341st Bombardment Group, 10th Air Force during World War II. He flew the B-25C, which was known for its ability to fly low and hit targets, said Gene Pfeffer, historian and curator of the National Museum of World War II Aviation in Colorado Springs, Colo.

A combination of British, American and Chinese forces fought in southeast Asia to hold the line against Japanese forces looking to invade China and India, with Americans focused on the aviation mission. Eventually the British would begin a ground campaign and push the Japanese out.

The twin-engine B-25 planes were used to target roads, railways, bridges and other supply lines of the Japanese forces to slow their progress north across Burma, now known as Myanmar.

“It was an especially dangerous thing because they were going as low as 50 feet,” Pfeffer said. “Ground fire was a really serious threat. If you’re hit badly at that low altitude, the chances of survival are very slim.”

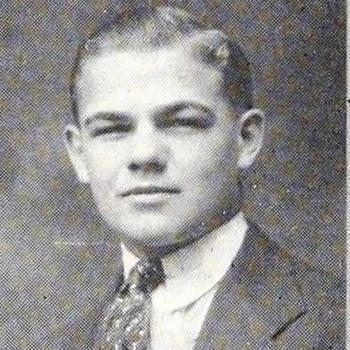

First Lt. Charles “Woody” McCook died in combat in World War II on Aug. 3, 1943. His remains were identified in April 2025 and he was buried in Georgetown, Texas, on Aug. 2, 2025. (Photo provided by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency)

News reports stated McCook had earned the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal for his role dropping supplies from aircraft to forward elements of the allied forces battling the Japanese in northern Burma. He racked up more than 200 hours of combat mission flights, according to the report.

On Aug. 3, McCook was the pilot for a six-man crew flying on a low-altitude bombing raid targeting a dam near Meiktila and nearby Japanese barracks, according to a 1944 news report on the crash. The crew had carried out its work by diving to 50 feet when a shell hit the plane’s gas lines.

Of the six people aboard the aircraft, two survived and were captured by Japanese forces, while the remaining four, including McCook, were killed. His remains were not recovered until after the war and he was declared missing in action.

The last letter his parents received from him — dated July 23 — arrived the day of the crash, according to an Aug. 16, 1943, news report that McCook was missing in action.

Sgt. John Boyd would be the only member of the crew to come home from the war after spending nearly two years as a Japanese prisoner of war in Rangoon.

Boyd described McCook in a news article “as the best in the business.” Boyd parachuted out of the plane and credited McCook’s flying for his ability to do so. McCook took the failing plane as high as it would go to enable his escape, Boyd said.

“Your parachute takes several hundred feet to open,” Pfeffer said. “You’ve got to get it up for somebody to get out of the airplane and to have some chance of survival.”

It was two years after the crash when McCook was declared dead. Not knowing what happened to her son was what bothered his mother the most, Benefiel said. Though it was not something the family ever really discussed.

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency identified McCook’s remains in April using dental, anthropological, and isotope analysis. Additionally, the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA analysis and mitochondrial genome sequencing data.

The three other crewmembers who died in the crash, Sgt. Sidney Burke, 1st Lt. Henry Carlin and 2nd Lt. Nathaniel Hightower, were also identified by DPAA.

On Thursday, Benefiel watched as the plane carrying McCook’s remains landed in Austin and received a water cannon salute. Considering she did not know her uncle, she was surprisingly moved, she said.

“I’m really glad [he’s home], if for no other reason than he’s back for my grandparents. I know they aren’t here, but I’m just going to believe that they know,” Benefiel said.