Kate O’Neill, 9, left, and her sister, Olivia O’Neill, 5, talk to Gene Simmons of Kiss as their great-grandfather, Hal Urban, sits atop a float as they prepare to take part in the National Memorial Day Parade on Monday. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

Harold “Hal” Urban, in the same dress wool Eisenhower jacket he wore after helping liberate a concentration camp 80 years ago, gave the man standing next to him a head-to-toe inspection Monday morning.

“He’s the one who sticks his tongue out?” Urban asked, before he met Gene Simmons on Memorial Day. “Not really my music. I like Bing Crosby and Lawrence Welk.”

Simmons, in leather pants, white snakeskin boots and dark glasses - no Kiss makeup - did not show his tongue when he met Urban.

He stuck his hand out and held Urban’s for a long, long beat, thanking the 100-year-old World War II veteran and Purple Heart recipient for his part in the iconic rocker’s history. Simmons’s mother, as a teen, was held in that concentration camp.

The men rode together on a sparkling, red-white-and-blue float through the nation’s capital in the 20th annual Memorial Day parade that afternoon, bonded by a war story.

Some fans shrieked for Simmons: “Rock and roll! Geeeeene!”

“Kiss is so American,” said Gabriel Lourenco, 38, a chef and culinary educator from Brazil now working in D.C. He once cooked for the Rolling Stones, so he came to his first Memorial Day parade to see a rock star.

Many cheered for Urban: “Thank you, sirrrr!”

“What a story,” said Danielle Singley, 43, who comes to D.C. from Baltimore for every Memorial Day parade to honor her family members who served.

David Logan, 68, who served in the Gulf War, said it’s important for veterans like himself and Urban to keep telling their stories for generations because “if it comes time for the next generation to serve, they’ll know why we did it and what it was for.”

The parade was a mix of local diehards, veterans and visitors.

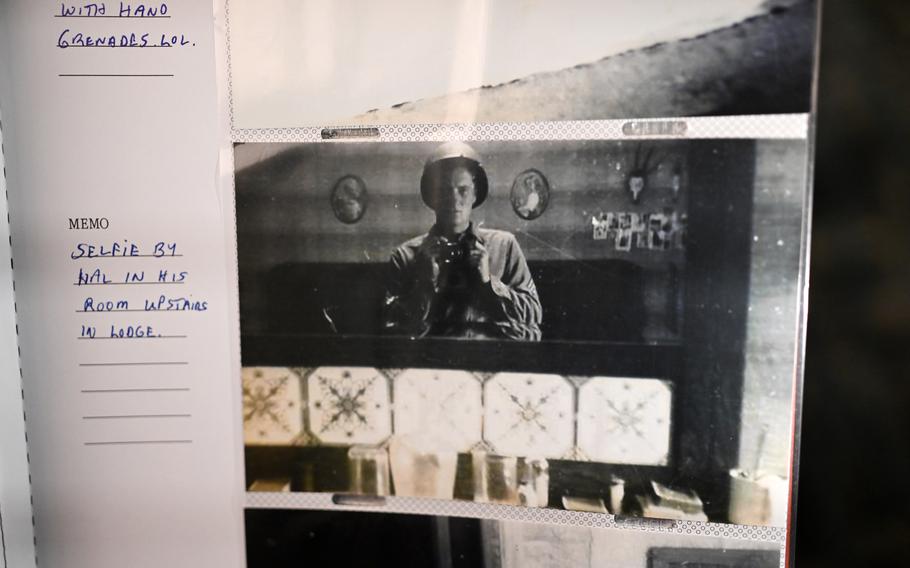

A self-portrait of Harold “Hal” Urban is seen in a photo album. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

Simmons and Urban met in a quiet room later to unpack their unlikely story.

Urban introduces himself as “101 in July,” when asked his age, not just 100. Ever forward-thinking.

Simmons, 75, told him: “When I grow up, I want to be just like you.”

It was only recently that Simmons learned the details of his mother’s harrowing life before immigrating to Israel and then Queens.

“My mother was in a concentration camp at 14 years of age,” he said.

Flora Klein spoke little of her life in Ravensbruck, a transfer camp, and Mauthausen, where she was 19 and the last survivor in her family when it was liberated on May 5, 1945.

“If it were not for the brave men like you,” Simmons said, pausing to hold back tears, “I wouldn’t be here. My mother wouldn’t have been here. Millions and millions of people wouldn’t be here. Even with the millions that were incinerated.”

Another long pause.

“I can’t say enough about this,” said the rock legend, tall and commanding when he entered the room and visibly humbled as he heard more from Urban, who was wounded in the Battle of the Bulge, then sent back to the front line while his shrapnel wound continued to bleed.

In an M3 half-track mounted with a .50 caliber machine gun ready to hit aircraft, Urban ran the roadblock when Mauthausen was liberated.

“The concentration camps were all run by SS,” he said. “They were the fanatics. You know, a lot of them did not want to surrender.”

He headed to the concentration camp on the second day.

“It was just a mess. People running all over. Some were crying, some were shouting … skinny and weak,” Urban said.

There’s no way to know if he met or saw Simmons’s mother, though they were both certainly there at the same time.

Earlier, Urban described the unshakable smell of burned flesh that permeated the camp. His fellow soldiers buried about 500 bodies that were in piles when the troops arrived. He didn’t tell that part to Simmons.

“It was a bigger emotional thing, seeing this, than combat,” he said. “Combat is what you’re trained to do. But you weren’t trained for that.”

About 90,000 people died in the camp along the Danube River near Linz, in the Austrian land annexed by Germany at the start of the war.

Urban left the Army on New Year’s Eve in 1945 with relentless nightmares.

“The psychologist at our VA said, when you start raising a family, they sort of go away,” Urban said. He had nine children and became a soybean farmer in Illinois. The nightmares subsided.

“And then when your family’s growing up, the psychologist said the nightmares start coming back,” he said. “Which they did.”

Martine Powers contributed to this report.