U.S.

AI deepfakes threaten to upend global elections, and no one can stop them

The Washington Post April 23, 2024

Divyendra Singh Jadoun, 31, a creator of deepfake content, poses against a green screen that he uses for generating videos using artificial intelligence in the deserts of Pushkar, India, on April 16, 2024. (Saumya Khandelwal/for The Washington Post)

Divyendra Singh Jadoun’s phone is ringing off the hook. Known as the “Indian Deepfaker,” Jadoun is famous for using artificial intelligence to create Bollywood sequences and TV commercials.

But as staggered voting in India’s election begins, Jadoun says hundreds of politicians have been clamoring for his services, with more than half asking for “unethical” things. Candidates asked him to fake audio of competitors making gaffes on the campaign trail or to superimpose challengers’ faces onto pornographic images. Some campaigns have requested low-quality fake videos of their own candidate, which could be released to cast doubt on any damning real videos that emerge during the election.

Jadoun, 31, says he declines jobs meant to defame or deceive. But he expects plenty of consultants will oblige, bending reality in the world’s largest election, as more than half a billion Indian voters head to the polls.

“The only thing stopping us from creating unethical deepfakes is our ethics,” Jadoun told The Post. “But it’s very difficult to stop this.”

India’s elections, which began last week and run until early June, offer a preview of how an explosion of AI tools is transforming the democratic process, making it easy to develop seamless fake media around campaigns. More than half the world’s population lives in the more than 50 countries hosting elections in 2024, marking a pivotal year for global democracies.

While it’s unknown how many AI fakes have been made of politicians, experts say they are observing a global uptick of electoral deepfakes.

“I am seeing more [political deepfakes] this year than last year and the ones I am seeing are more sophisticated and compelling,” said Hany Farid, a computer science professor at the University of California at Berkeley.

While policymakers and regulators from Brussels to Washington are racing to craft legislation restricting AI-powered audio, images and videos on the campaign trail, a regulatory vacuum is emerging. The European Union’s landmark AI Act doesn’t take effect until after June parliamentary elections. In the U.S. Congress, bipartisan legislation that would ban falsely depicting federal candidates using AI is unlikely to become law before the November elections. A handful of U.S. states have enacted laws penalizing people who make deceptive videos about politicians, creating a policy patchwork across the country.

In the meantime, there are limited guardrails to deter politicians and their allies from using AI to dupe voters, and enforcers are rarely a match for fakes that can spread quickly across social media or in group chats. The democratization of AI means it’s up to individuals like Jadoun — not regulators — to make ethical choices to stave off AI-induced election chaos.

“Let’s not stand on the sidelines while our elections get screwed up,” said Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., the chair of the Senate Rules Committee, in a speech last month at the Atlantic Council. “ … This is like a ‘hair on fire’ moment. This is not a ‘let’s wait three years and see how it goes moment.’ ”

Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., at the United States Capitol in Washington in March 2023. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

For years, nation-state groups flooded Facebook, Twitter (now X) and other social media with misinformation, emulating the playbook Russia famously used in 2016 to stoke discord in U.S. elections. But AI allows smaller actors to partake, making combating falsehoods a fractured and difficult undertaking.

The Department of Homeland Security warned election officials in a memo that generative AI could be used to enhance foreign-influence campaigns targeting elections. AI tools could allow bad actors to impersonate election officials, DHS said in the memo, spreading incorrect information about how to vote or the integrity of the election process.

These warnings are becoming a reality across the world. State-backed actors used generative AI to meddle in Taiwan’s elections earlier this year. On election day, a Chinese Communist Party affiliated group posted AI-generated audio of a prominent politician who dropped out of the Taiwanese election throwing his support behind another candidate, according to a Microsoft report. But the politician, Foxconn owner Terry Gou, had never made such an endorsement, and YouTube pulled down the audio.

Taiwan ultimately elected Lai Ching-te, a candidate that Chinese Communist Party leadership opposed — signaling the limits of the campaign to affect the results of the election.

Microsoft expects China to use a similar playbook in India, South Korea and the United States this year. “China’s increasing experimentation in augmenting memes, videos, and audio will likely continue — and may prove more effective down the line,” the Microsoft report said.

But the low cost and broad availability of generative AI tools have made it possible for people without state backing to engage in trickery that rivals nation-state campaigns.

In Moldova, AI deepfake videos have depicted the country’s pro-Western President Maia Sandu resigning and urging people to support a pro-Putin party during local elections. In South Africa, a digitally altered version of the rapper Eminem endorsed a South African opposition party ahead of the country’s election in May.

In January, a Democratic political operative faked President Joe Biden’s voice to urge New Hampshire primary voters to not go to the polls — a stunt intended to draw awareness to the problems with the medium.

The rise of AI deepfakes could shift the demographics of who runs for office, since bad actors disproportionately use synthetic content to target women.

For years, Rumeen Farhana, an opposition party politician in Bangladesh, has faced sexual harassment on the internet. But last year, an AI deepfake photo of her in a bikini emerged on social media.

Farhana said it is unclear who made the image. But in Bangladesh, a conservative majority Muslim country, the photo drew harassing comments from ordinary citizens on social media, with many voters assuming the photo was real.

Such character assassinations might prevent female candidates from subjecting themselves to political life, Farhana said.

“Whatever new things come up, it’s always used against the women first. They are the victim in every case,” Farhana said. “AI is not an exception in any way.”

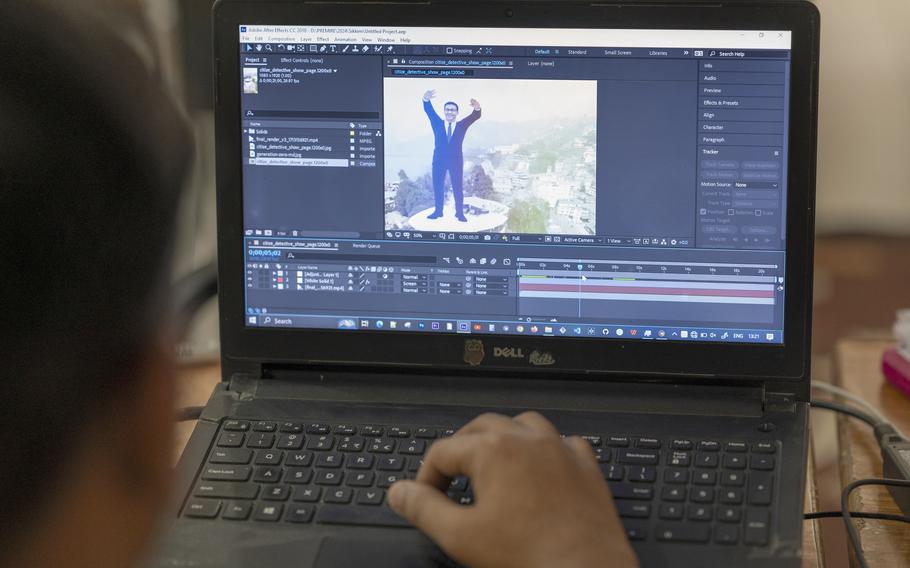

An employee works on a political-content project at the office of Polymath Solutions in Rajasthan, India, on April 16, 2024. (Saumya Khandelwal/for The Washington Post)

In the absence of activity from Congress, states are taking action while international regulators are inking voluntary commitments from companies.

About 10 states have adopted laws that would penalize those who use AI to dupe voters. Last month, Wisconsin’s governor signed a bipartisan bill into law that would fine people who fail to disclose AI in political ads. And a Michigan law punishes anyone who knowingly circulates an AI-generated deepfake within 90 days of an election.

Yet it’s unclear if the penalties — ranging from fines up to $1,000 and up to 90 days of jail time, depending on municipality — are steep enough to deter potential offenders.

With limited detection technology and few designated personnel, it could be difficult for enforcers to quickly confirm if a video or image is actually AI-generated.

In the absence of regulations, government officials are seeking voluntary agreements from politicians and tech companies alike to control the proliferation of AI-generated election content. European Commission Vice President Vera Jourova said she has sent letters to key political parties in European member states with a “plea” to resist using manipulative techniques. However, she said, politicians and political parties will face no consequences if they do not heed her request.

“I cannot say whether they will follow our advice or not,” she said in an interview. “I will be very sad if not because if we have the ambition to govern in our member states, then we should also show we can win elections without dirty methods.”

Jourova said that in July 2023 she asked large social media platforms to label AI-generated productions ahead of the elections. The request received a mixed response in Silicon Valley, where some platforms told her it would be impossible to develop technology to detect AI.

OpenAI, which makes the chatbot ChatGPT and image generator DALL-E, has also sought to form relationships with the social media companies to address the distribution of AI-generated political materials. At the Munich Security Conference in February, 20 leading technology companies pledged to team up to detect and remove harmful AI content during the 2024 elections.

“This is a whole-of-society issue,” said Anna Makanju, OpenAI vice president of global affairs, during a Post Live interview. “It is not in any of our interests for this technology to be leveraged in this way, and everyone is quite motivated, particularly because we now have lessons from prior elections and from prior years.”

Yet companies will not face any penalties if they fail to live up to their pledge. Already there have been gaps between OpenAI’s stated policies and its enforcement. A super PAC backed by Silicon Valley insiders launched an AI chatbot of long-shot presidential candidate Dean Phillips powered by the company’s ChatGPT software, in violation of OpenAI’s prohibition on political campaigns’ use of its technology. The company did not ban the bot until The Washington Post reported on it.

Jadoun, who does AI political work for India’s major electoral parties, said the spread of deepfakes can’t be solved by government alone — citizens must be more educated.

“Any content that is making your emotions rise to a next level,” he said, “just stop and wait before sharing it.”

Divyendra Singh Jadoun, a deepfake creator and founder of Polymath Solutions, works at his office in Pushkar constituency in the Indian state of Rajasthan on April 16, 2024. (Saumya Khandelwal/for The Washington Post)