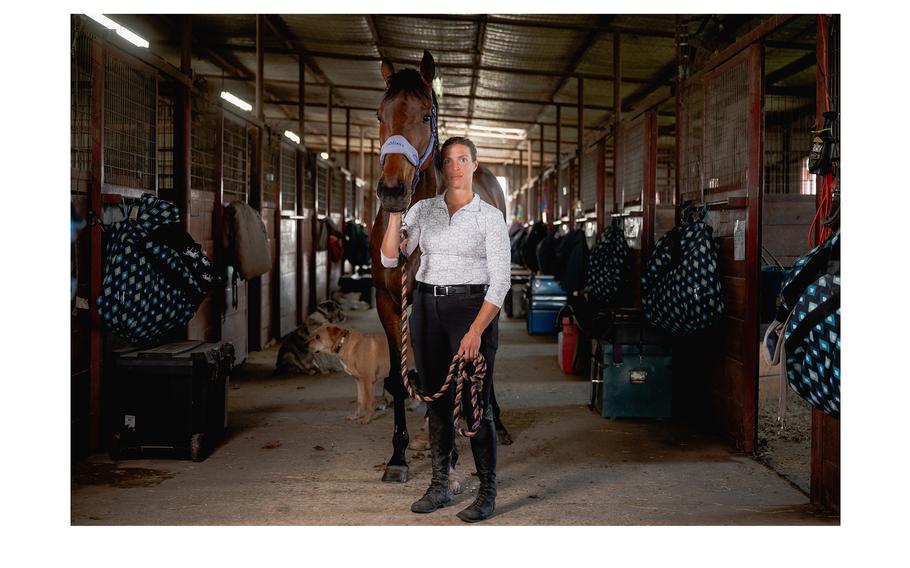

Ellen Doughty watches a student during a private lesson at Rockwall Hills Equestrian Center in Rockwall, Texas. (Desiree Rios for The Washington Post)

ROCKWALL, Tex. - Stormy Daniels had decided to go public with her accusations.

“I’m taking a stand for those who don’t have a voice,” she announced in a long Facebook post. “My only regret is that I waited so long.”

It was December 2016 - more than a year before Daniels would break her silence about an alleged sexual encounter with Donald Trump. Her target was not a national political figure, but a Dallas-area horse trainer, Ellen Doughty, who Daniels claimed had mistreated her animals.

Doughty forcefully denied the allegations, which Daniels also published on a popular equestrian website. It was the opening salvo in a feud that has grown into a multimillion-dollar court battle and ensnared some of the top officials in the rarefied world of competitive English riding. Along the way, there have been four dead horses - one of which did not stay buried - and a trail of recriminations that can seem as endless as the plains of North Texas.

At the center is Daniels, a lifelong horse lover better known to millions of Americans as history’s most politically consequential adult-film actress. When Trump stands trial this month in New York on charges of falsifying business records to hide a hush money payment made in the fall of 2016 - the first-ever criminal prosecution of a former American president - Daniels may be called as a key witness. Trump, who denies having sex with Daniels, has pleaded not guilty, saying the payment was made to prevent “false and extortionist accusations.”

But the woman who was paid $130,000 to bury her account of a couple of minutes of sex in a Lake Tahoe hotel room has simultaneously been involved in another legal drama unfolding far from cable news studios and big-city courthouses.

The dispute, largely ignored in the avalanche of media attention devoted to Daniels over the past six years, offers a new vantage on one of the most polarizing figures of the Trump era. It highlights the extent to which the same dynamics that surround her on the national stage have followed her off it: questions about her motivations and credibility, the adulation of supporters who say she’s standing up for the truth, and a large amount of money at stake.

Doughty, 39, is suing Daniels for defamation, seeking up to $2 million in damages for what she says was an orchestrated campaign to destroy her reputation. The longtime equestrian instructor and top-rated competitive rider alleges that Daniels broadcast a set of falsehoods that drove her business to the brink of ruin.

“I wouldn’t trust her farther than I can spit,” Doughty said in an interview with The Washington Post. “She’ll say whatever - she’ll say something to you, and something else to you, in the same day - if she thinks it’s going to help her, whether it be money, whether it be fame or power.”

Daniels, 45, declined to comment for this article through her attorney, Clark Brewster of Tulsa. Brewster also declined to answer a list of detailed questions from The Post.

In court documents, he has argued that Daniels, also known as Stephanie Clifford, was exercising protected rights to free speech on “a matter of public concern” when she criticized Doughty’s treatment of horses. The defamation lawsuit is “retaliation” for actions Daniels took out of her “desire to bring to light [Doughty’s] dangerous training and endangerment of horses and their riders,” Brewster asserts.

Daniels is not Doughty’s only detractor. After she went public with her criticisms, nine additional horsewomen eventually submitted formal complaints to the United States Eventing Association, the governing body for the equestrian triathlons - consisting of dressage, cross-country and show jumping - that are perhaps the most demanding form of English riding. A panel of association officials revoked Doughty’s certification as an instructor.

Doughty’s certification was reinstated, however, after she challenged the veracity of the allegations against her. An Eventing Association official privately expressed misgivings about Daniels’s truthfulness, according to emails that have come to light through the lawsuit. And a government animal-control inspector who investigated Doughty’s facility at the height of the conflict in response to repeated phone calls from tipsters - at least one of whom used a false name - determined that the facility was “clean” and “beautiful” and that the “accusations are unfounded.”

Since Daniels spoke out about Trump in 2018, Americans have been divided in their views of her. Many of the former president’s critics have elevated her to the role of savior and heroine, a woman unwilling to be silenced by a uniquely powerful man.

To Trump’s supporters, she is a mendacious opportunist who accepted a lot of money in exchange for a promise not to spread a story that she has now recited in TV interviews, a best-selling book and, just last month, a feature-length documentary.

Daniels herself has often lamented the consequences of speaking out against Trump, saying she and her family have been threatened and ridiculed. She also owes the former president nearly $440,000 in attorney’s fees - not including interest - for unsuccessful defamation lawsuits, according to Harmeet K. Dhillon, Trump’s attorney in those cases. The suits were filed by Daniels’s former lawyer, Michael Avenatti, who is now in prison for embezzling money from her and other clients.

“It cost me everything,” she said last month on ABC’s “The View” of her stand against Trump, adding that she wants nothing more than to enjoy peace and quiet with her family and her horses - animals that she says have offered her a refuge since her troubled childhood in Baton Rouge.

“I don’t even like politics,” she said. “I just want to be at home. I don’t want to wear makeup, or put on pants that aren’t riding pants. I want to ride my horse. I want to play with my daughter.”

Ellen Doughty stands with Breakin’ All the Rules, a bay mare, after riding at Rockwall Hills Equestrian Center. (Desiree Rios for The Washington Post)

But peace can be a rare commodity in America’s subculture of moneyed horse enthusiasts, a world of strong animals and stronger personalities where “barn politics” can be at least as vicious as anything inside the Beltway. And if her fight with Doughty shows anything, it is that Daniels’s involvement in equestrian circles has been far from quiet.

‘The life I wanted’

According to Daniels, there has scarcely been a time when horses weren’t an important part of her life.

In her 2018 memoir, “Full Disclosure” - which opens with a photo of a young Daniels riding - she writes about her first horse, a black mare named Perfect Jade, bought with $500 she says was given to her by her stepdad when he was drunk.

“People who knew Jade’s history told me I saved that horse, but she saved me,” she writes. “Since I hated being home, if I hadn’t had the barn to go [to,] I would have just hung around my little crack neighborhood, smoking and drinking with the other kids my age. I was too busy going to horse shows on the weekends to spend time at the mall flirting with boys.”

Daniels remained a committed horsewoman around her jobs as a stripper, then as an actor in and director of pornographic films. In 2014, she and her then-husband moved to the small city of Forney, Tex. Daniels rejoiced that “being in Texas meant I could pursue a horse career,” she writes in “Full Disclosure,” adding, “I had worked so hard to have the life I wanted.”

Their new home was on the eastern fringe of the Dallas suburbs, where new subdivisions give way to prairie and pastureland. Daniels took lessons at a barn about 20 minutes’ drive from her house.

Her instructor was an up-and-coming event rider named Ellen Doughty.

Like Daniels, Doughty came from the kind of modest background that is uncommon in the world of competitive riding. She was the daughter of a police officer, grew up outside Detroit and worked hard to make her way in a sport dominated by kids with deep-pocketed parents. Unlike Daniels, she had devoted herself full time to the equestrian world, and had risen to its heights, gaining buzz as a possible Olympic prospect.

When Doughty started her own barn - Rockwall Hills Equestrian Center, on 100 acres at the end of All Angels Hill Lane in Rockwall, Tex. - Daniels followed her, at one point boarding seven horses there. Although Daniels sometimes paid for alfalfa in cash dusted with glitter, Doughty said, she was in many ways like any other client. Both she and her young daughter took lessons from Doughty and traveled with her to weekend events.

Their relationship extended beyond the stables. Doughty said she sometimes hosted Daniels’s daughter at her home for overnight visits while her mother was away shooting films or on exotic-dancing tours. The child was a flower girl at Doughty’s 2014 wedding in Kentucky - and Daniels performed a strip show at the groom’s bachelor party.

Occasionally, Daniels boasted of her acquaintance with Trump, best known at the time as a reality television star. She would later assert that they had sex after meeting at a celebrity golf tournament in 2006, nearly a decade before Daniels moved to Texas. But among horsefolk, she never mentioned such an intimate encounter, and spoke positively about Trump, Doughty said.

“She kept saying, like, ‘I know Donald personally and he’s a gentleman,’” recalled Doughty, who said she doesn’t follow politics closely but voted for Trump in 2016 and 2020.

In June 2015, flash floods ravaged Texas after weeks of heavy rain. Bailey, a horse belonging to Daniels, was swept away from a low-lying pasture and drowned. Although Doughty’s insurance paid for the horse, Daniels did not initially blame her trainer.

“It was my job to keep him safe and I failed him,” she wrote on Facebook the day the horse died. “I know most of you reading this have horses. If there is ANY chance of your barn flooding with the recent rains, don’t risk it … Please don’t make the same mistake. I’ll never forgive myself.”

Daniels and her horses stayed at Doughty’s barn for another year. But in the summer of 2016, she said she would be moving them - and then complained about the treatment of her animals after Doughty requested she pay over $2,000 in outstanding expenses.

“I, therefore, must do what I feel is right for the safety of the animals that I love and I am responsible for,” Daniels wrote in a Sept. 5 email to Doughty, refusing to pay most of her last invoice and claiming that her horses had been neglected and underfed. “I’d hope you’d understand that but pretty sure that won’t be the case …”

Daniels was soon busy negotiating over a much larger sum of money.

In October 2016, she agreed to accept $130,000 - funneled through Michael Cohen, then Trump’s attorney and fixer - to keep quiet about the alleged tryst in Tahoe, according to the Manhattan district attorney’s office. The deal averted what Trump’s advisers feared could be a coup de grâce for a campaign reeling from The Post’s publication of a tape in which Trump boasted about sexually assaulting women.

Doughty, meanwhile, let the matter of the unpaid barn bill drop. And there her dispute with Daniels might have ended had fate not intervened and added to the equine body count.

‘I want her head on a stick’

A few months after Daniels moved her family’s horses to a new location, two of them - Danger Mouse and Ziggy Star Rocker - died after a collision with each other while galloping in a field. It was an unheard-of freak accident, even by the standards of animals notorious for finding strange ways to hurt themselves.

Doughty posted a comment on Instagram about Mouse that she insists was a sincere condolence, but Daniels and her then-husband, Glendon Crain, interpreted it as a snide attack. (The exchange was deleted and The Post was unable to view it.)

“Mouse told me to tell you to F--- OFF, he never liked you anyways,” Crain wrote in a text message to Doughty that was shared with The Post, which has dashed out most profanity in this article. “Everyone else is celebrating what a LEGEND he was, but your narrow tiny little hollow mind will never understand it...”

“Mouse was under my care for several years and I really loved that horse, I am so sad to hear about what happened,” Doughty texted back. “I don’t think creating stories or personal attacks on me is a very adult way of handling things.”

Crain, who according to court records is now representing himself in the defamation lawsuit, did not respond to messages.

Just before 6 a.m. on Dec. 21, 2016, Daniels published a lengthy post in the online discussion forum of the Chronicle of the Horse - the 87-year-old publication that is the primary source for news and gossip in America’s equestrian community - that detailed her “horrible experiences” with Doughty. Among her complaints was that Bailey had been placed in the pasture where he drowned against her wishes and that Doughty had inappropriately delayed treating colic in her daughter’s pony, Lil Yella Fella, resulting in an emergency surgery.

The post - which has grown into a thread of more than 1,600 comments - also assailed Doughty’s conduct as a barn manager and trainer, claiming she let her dogs run loose at equestrian shows and used “low-quality hay that most of my horses refused to eat.”

“Sharing your personal experiences publicly is NOT slander if it is TRUE,” Daniels wrote.

The conflict soon spilled beyond the internet.

In early 2017, Daniels and seven other riders filed formal complaints against Doughty with the United States Eventing Association, claiming among other things that she pushed students to jump obstacles beyond their abilities and taught overly aggressive riding techniques. Robbie Peterson, then co-owner of MeadowCreek Park Horse Trials in Texas, wrote in a letter that Doughty “is often unsafe with her decisions for both horses and riders in her program.”

But Doughty also had supporters. More than half a dozen people wrote testimonials in her defense, including current or former students and employees who said Doughty was a “wonderful” trainer and “excellent role model” who “gives it her all to make sure every horse and rider is safe and well educated.”

Doughty denied most of the allegations, although she acknowledged she could do a better job of keeping her dogs on leashes at events. In July 2017, the Eventing Association decided there was insufficient evidence to take away her instructor certification.

Daniels didn’t give up, however, and six weeks later reached out to Erin Walker, a rider who had been among Doughty’s most vocal supporters but had recently left her barn, according to court records. After communicating with Daniels, she recanted a letter she’d written to equestrian authorities defending Doughty.

In a caustic dialogue that Doughty’s lawyer, Christine Renne, would later characterize as “‘Mean Girls’ on steroids” - the word “bitch” appears 26 times, often preceded by obscene adjectives, in the 126 pages of messages between Daniels and Walker produced as evidence in the lawsuit - the pair disparaged Doughty and discussed how to spread word of her alleged misdeeds.

“I want her head on a stick,” Daniels wrote to Walker in September 2017.

“I will wreck her s--- one way or another,” Walker wrote to Daniels in another exchange.

Walker declined to comment for this article through her attorney. In court pleadings, she has argued that Doughty’s lawsuit was retaliation for her complaint to the Eventing Association.

In January 2018, the association opened a new case against Doughty based on complaints from Walker and another former student, Kelsy Silvey, who according to Walker’s messages was also communicating with Daniels. Among Silvey’s accusations was that the carcass of one of Doughty’s horses, Beaux, had been left to rot above ground on her property.

Doughty again denied the allegations, saying the bones of Beaux had been exposed on a remote part of her property by erosion months after his burial. Nevertheless, in February an association panel removed her certification. Although the move did not prevent Doughty from giving lessons, it meant she could no longer advertise herself as one of the association’s approved instructors.

By this time, Rockwall Hills Equestrian Center was steadily losing customers and having trouble attracting new ones. Rumor runs faster than a thoroughbred in equestrian circles, abetted in Doughty’s case by search algorithms: Daniels’s incendiary post on the Chronicle of the Horse had become (and today remains) a top result for any prospective student or boarder who might choose to Google Doughty’s name.

Ellen Doughty coaches during a group lesson at Rockwall Hills. (Desiree Rios for The Washington Post)

Faced with what she would later say in a sworn declaration were losses of about $5,000 a month, Doughty filed a defamation lawsuit against Daniels, Crain, Walker and Silvey in July 2018.

Daniels initially reacted with bravado, sending a photo of the lawsuit to Walker.

“Are we going to destroy this bitch finally?” she wrote. “Our evidence is undeniable.”

Horse people

But some outside observers had begun to view the evidence with less confidence.

In a January 2018 email, Sue Hershey - manager of the Eventing Association’s instructor certification program - confronted Daniels with the apparent contradiction between her June 2015 Facebook post about Bailey, who drowned in the flash flood, and her later claims that Doughty was responsible for the horse’s death.

“Read what you yourself wrote,” Hershey argued. “How can you ask others to blame [Doughty] for this decision - when, in fact, you are here blaming yourself for it in your own written words?”

“I DO blame myself for my horses being down there because I should have been much firmer with Ellen about NOT wanting them down there AT ALL,” Daniels wrote back, adding that she was away in Los Angeles during the floods. “I gave in because she said the grass was better and SWORE that they would be brought up” if it rained. (Doughty denied this, saying the horses were being kept in the pasture on instructions from Daniels.)

Daniels also fumed in messages to Walker that Hershey was “basically calling me a liar,” later calling the association official “a moron.”

Hershey also emailed Walker, saying her recent discovery of Daniels’s earlier Facebook post “was shocking to me because I had trusted that she had been telling me the truth.”

The tensions coincided with Daniels’s dramatic entrance onto the nation’s political scene. In January 2018, the Wall Street Journal broke the news that Trump’s attorney had arranged to buy her silence, and by the end of March, Daniels had appeared on “60 Minutes” to recount her story. But while Daniels was becoming a household name, Doughty began to successfully beat back the allegations against her.

Doughty asked for a new hearing from the Eventing Association, pointing out that the accusations had not been made under oath and that the association had never contacted witnesses whose statements she had submitted in her defense. The association agreed to rehear the case, but Walker said she no longer wanted to proceed with her complaint against Doughty, telling an association official in an email that she wanted to “move on with my life and go on about my business and forget I ever met her.”

After more than a year of inaction, Doughty was reinstated as a certified instructor in the summer of 2019. In 2020, the Eventing Association was named as an additional defendant in her lawsuit, over its alleged mishandling of her case.

Hershey died in 2021. Officials at the Eventing Association did not respond to requests for comment. Neither did the association’s attorney. The group, which is based in Virginia, has argued in pleadings that it is not subject to the jurisdiction of Texas courts.

Silvey could not be reached for comment. She has never responded to the defamation complaint, and no lawyer has ever appeared on her behalf in court.

As facts emerged in the lawsuit, it became clear that some expert arbiters of horse health had found little to criticize in how Doughty ran her barn. David Celella, one of the state’s top equine veterinarians, said in a sworn declaration that he had been visiting Doughty’s facility for years and that her horses “are healthy and well cared-for.”

Joyce Ross, an animal care and control officer with the city of Rockwall, made an unannounced visit to the farm after a flurry of complaints over several days in the summer of 2017 and found nothing wrong. “The whole place was beautiful,” she wrote in her inspection report.

Since then, animal control officers have visited Doughty’s barn seven times in response to periodic complaints, according to reports obtained by The Post through a public-records request. None of those inspections led to citations, the reports show, although Doughty agreed not to bring two of her fiancé’s dogs on the property again after a horse was chased and bitten last December.

The Post called the two people whose names and numbers were listed in the 2017 animal-control complaints. (Others were anonymous.) Both live outside Texas. One did not respond and the other, Kerry Couch of Illinois, said that she did not know Doughty, that she had never contacted the city of Rockwall and that someone else must have fraudulently used her name. (Couch, now retired, was once a high-level rider and trainer.)

After speaking with The Post, she said, she called the city to remove her name from the case file.

Couch said that while the details of the Daniels-Doughty feud sounded extreme, drama among bipeds was an unfortunate fact of the riding life, particularly at more-advanced levels of training and competition. Some less-experienced riders don’t react well, she said, to the commanding personalities that often ascend to the top ranks of a dangerous sport that demands unerring control over 1,200-pound animals.

“You have to have a competitive drive. You have to have an ego. You have to have an element of fearlessness to do that and survive,” Couch said, adding that these qualities must also be wedded to extreme self-discipline and technical prowess. “The competitiveness between riders in the same barn, that can blow up sometimes.”

A similar sentiment was voiced less decorously by Trent Hyde, who on a recent evening at Doughty’s barn leaned across the rail of a metal gate as he watched his teen daughter’s jumping lesson.

“Horse people are crazy,” said Hyde, 59, a lifelong resident of North Texas who has boarded horses with Doughty for seven years. He said the turmoil that followed Daniels’s departure was unfortunate, but scoffed at the accusations that Doughty mistreated either horses or humans.

“She’s hard on these girls,” Hyde said, nodding at Doughty, who was calling out instructions to his daughter and two other mounted riders in the arena. “But they’re strong, independent women when they’re done.”

Daniels moved to Central Florida in 2022. But she wasn’t done battling over horses in North Texas. Last year, she sued Michelle Cheney, owner of Southern Cross Equestrian, the facility where Daniels ultimately moved her animals after her departure from Rockwall Hills.

The dispute arose over Cheney’s foreclosure on Leo, a Dutch Warmblood that she said Daniels left in her care for years without paying overdue invoices, according to court records. Cheney, who declined to comment, countersued, and after about nine months the case was settled out of court.

Doughty’s lawsuit continues to inch along after almost six years. Delayed by multiple trips to the Texas Court of Appeals over pretrial disputes, it is nowhere near being resolved. But the fallout from what Daniels began saying about her in 2016 has never really stopped.

Just last month, commenters on Daniels’s Chronicle of the Horse thread began adding screenshots of an advertisement for a kids’ summer camp at Rockwall Hills Equestrian Center, asking that people “get the word out that this is NOT a safe option for children.”

Doughty said that quieting such accusations is more important to her, at this stage, than any damages a judge might or might not award.

“I just want to move on with my life,” she said. “It would be nice to be financially compensated for all the loss we’ve had. But honestly, at this point, it’s really about clearing my name.”

Daniels, meanwhile, is preparing speak out once again, to what may be the most important audience she has ever faced: the judge and jury who will decide the outcome of Trump’s hush money trial. Prosecutors have not yet said whether they plan to summon her to the witness stand.

But she says she is ready - and eager - to tell her story.

“I’m hoping with all of my heart that they call me,” she said during her recent appearance on “The View.” “I relish the day that I get to face him and speak my truth.”

Razzan Nakhlawi contributed to this report.