Kristen Mello, who has lived in Westfield, Mass., most of her life and is now a city councilor, suspects contamination of the city’s drinking water with PFAS, or “per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances,” may be to blame for serious health issues she has faced. (Don Treeger, The Republican/TNS)

WESTFIELD, Mass. (Tribune News Service) — When Kristen Mello was hospitalized in 2013 with pneumonia, doctors found one of her lungs was crushed. They performed emergency surgery to remove the bottom section of her left lung.

“It wasn’t until months later when I saw the pathology report that I found out that my lung had gone necrotic and it was breaking down inside of my body,” Mello said.

In the months leading up to her illness, she had been on a health kick, training for a 5K and drinking a gallon of tap water a day. “We thought we were detoxing,” Mello said.

Years later, she thinks the water was the problem. Mello, who has lived in Westfield most of her life and is now a city councilor, suspects contamination of the city’s drinking water with PFAS, or “per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances,” may be to blame for serious health issues she has faced.

“Are my suspicions high? Yes they are,” Mello said. “Do I know 100% for sure? No, I don’t.”

There is almost too much to know about these “forever chemicals.” A long effort to understand the extent of the problem in Westfield is ramping up this year. This story provides essential facts about one of today’s most vexing public health problems.

PFAS, a group of thousands of manufactured chemicals, are found in a wide range of products. They don’t easily break down and can accumulate in the body. At certain levels, they can be harmful to human health, including by weakening the immune system.

In the 1970s, the Air Force started using firefighting foam that contained PFAS, including at Barnes Air National Guard Base. The chemicals seeped into the ground and there’s mounting evidence it polluted the water. The issue surfaced to the public in 2016 when regulations changed and levels of PFAS found in some of the city’s wells years earlier exceeded new federal limits; the city notified residents.

In the years since her emergency surgery, Mello has become a PFAS activist and director of Westfield Residents Advocating for Themselves. She is now looking to join litigation against firefighting foam manufacturers, including 3M.

Years after residents learned these chemicals had been in their drinking water, some still worry about the impact the exposure had on their health. At least a few like Mello are joining a lawsuit.

City drinking water is now treated specifically for the chemicals, but it’s at an expense the chemical manufacturers don’t bear — at least not yet. Litigation the city and state filed in federal court aims to hold the companies that made and sold the PFAS-laden firefighting foam financially accountable.

So far, none of the chemicals that contaminated the ground and aquifer underneath Barnes Air National Guard Base have been cleaned up. The “plume” of PFAS contaminants continues to seep deeper into the aquifer underneath the air base, and it’s not known how far and wide they have spread. Community members and leaders at the base continue to meet to discuss the situation and work toward remediation.

Westfield is far from alone: It’s one of a growing number of communities around the country grappling with these “forever chemicals” and their environmental and public health impact.

Col. David L. Halasi-Kun is wing commander of the 104th Fighter Wing at Barnes Air National Guard Base in Westfield, Mass. “The last thing we want to have is any perception that were trying to hide any information,” he said. (Don Treeger, The Republican/TNS)

Investigation at Barnes Air Base

In the 1970s, the Air Force started using aqueous film forming foam, which contains PFAS, to fight fires. It helps suppress a fuel or oil fire, which can’t be put out with just water.

At Barnes, a former fire training area is one of the primary PFAS sources, according to an inspection report. Foam was used to put out fires for training, and there wasn’t a cleanup process like there is today if fire suppressants — which now use a different formulation — are used, said Colonel David L. Halasi-Kun, wing commander of the base.

In 2016, the public was notified about high PFAS levels in the water. That year, the Environmental Protection Agency lowered the lifetime levels it considered safe, which made previous test results of PFOS and PFOA — two of the most-commonly studied PFAS chemicals — from some wells in the city too high.

The state told the base in 2016 that its past use of firefighting foam was potentially responsible for the contamination of the water supply and required it to take action.

Since then, Barnes Air Base has completed multiple investigations of the site, analyzing soil and water samples, one at the base in 2018 and another in 2020 that includes areas outside the base’s boundaries. The chemicals were found to be present at the base. Tests inside and outside the airport’s boundary showed PFAS chemicals in firefighting foam at levels above state limits. The report linked the base to PFAS contamination of public water systems, but also says that there could be other additional sources to blame.

The site’s overall relative risk — a scale the Department of Defense uses to determine the risk to public safety, human health, or the environment — is categorized as high, a 2021 Air National Guard evaluation concludes.

In 2021, Westfield formed a Restoration Advisory Board (RAB), a provision by the Department of Defense to include the public in environmental cleanup efforts. Not all towns dealing with contamination have a board, but the city of Westfield was vocal about creating one. Westfield’s RAB meets quarterly and is made up of members from the National Guard, state Department of Environmental Protection, state representatives, and local residents.

“The RAB is the most powerful tool to make sure the community’s voice is heard regarding the environmental restoration activities at Barnes,” said Chris Brown, restoration program manager for the National Guard covering New England states.

“The last thing we want to have is any perception that we’re trying to hide any information,” said Halasi-Kun, who represents the base as co-chair of the restoration board. “We’re as much Westfield as Westfield is us. The tap water that I’m drinking down in my office is the exact same tap water that the people in the community of Westfield are drinking.”

The next step: a remedial investigation.

Brown expects the project will last several years. A contractor team will visit the base late this summer or fall to drill holes and take samples of water and soil, Halasi-Kun said. Those experts will map out where the PFAS contamination has spread, including beyond the initial site, and look at how deep the chemical plume has seeped into the aquifer.

“It’s a forever chemical that is forever settling lower and lower,” Halasi-Kun said.

Unlike a spill of fuel that would float on water, PFAS dissolves, said David F. Boutt, a professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in the Department of Earth, Geographic, and Climate Sciences. “It just moves into the water, moves with the water and can be distributed very, very quickly over large areas.”

Boutt reviewed technical government reports and data on the site and summarized his findings in an analysis finished late last year, an initiative paid for with grant funding the Restoration Advisory Board secured.

He was disappointed past reports didn’t include mapping of the contamination in the aquifer, his report says.

“I think they’re pretty naive about where the contamination is going, in my opinion,” he said. “The Air National Guard has spent a lot of money trying to understand what’s happening. We still don’t know what the true extent of the contamination is.”

As the plume of PFAS chemicals moves, it could taint wells that don’t yet have problems, he said.

The Department of Defense paid to investigate the PFAS problem at Barnes, according to Halasi-Kun. There’s a wave of need for PFAS cleanup projects at military sites; more than 700 places may have used PFAS, according to the Department of Defense’s PFAS Task Force.

Halasi-Kun wants to push the Barnes project along so it’s at the top of the list and gets funded.

“I think there will come a time where the need is greater than the funding that is available. That’s pure speculation. That’s not the official Air Force opinion,” he said.

It will be years — possibly a decade — until the Barnes site is remediated, Halasi-Kun said.

The air base is trying to be thorough, said advisory board member and Westfield resident Mary Ann Babinski. “It’s very frustrating — everything takes time,” she said.

While studies at the air base are ongoing, the board is looking to examine the impact the contamination has had on human health. It’s working to secure a federal grant that would pay for experts to analyze existing health data and look for potential links to PFAS.

In a separate project, a team from the University of Massachusetts will be collecting health information from residents who want to participate to gather possible PFAS-related concerns.

“The idea is to say: We know that we had this stuff in our water, and we know that they’re associated with health effects in other communities,” said Mello, the leader of WRAFT, which got a state grant to pay for the project. “Does anybody want to talk about what effects they might be experiencing and see if maybe that’s an unusual number?”

The community group is also planning to hold events to discuss current research on PFAS, Mello said.

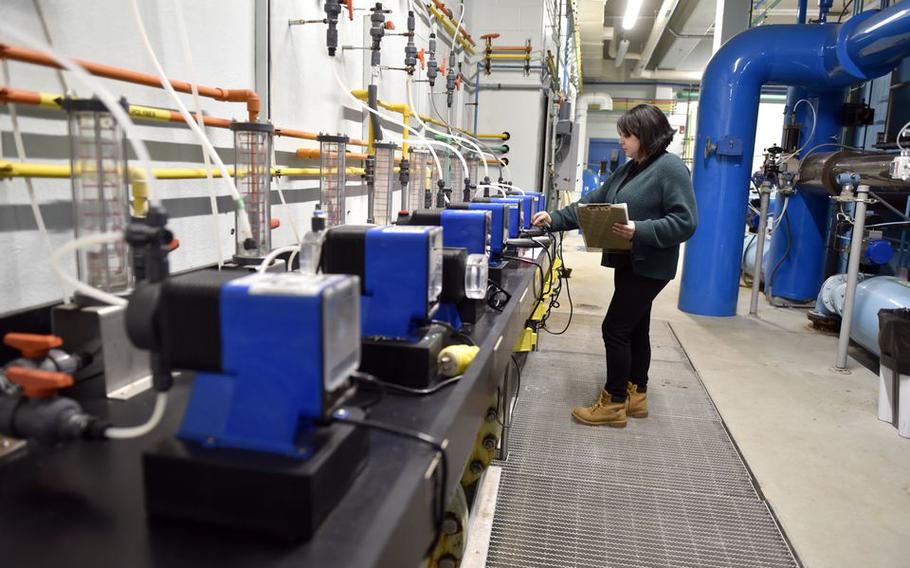

Brenda Lopez, head treatment plant foreman for Westfield’s Public Works Water Treatment Division, checks filter readings at the Reservoir Road filter station in Southwick, Mass. (Don Treeger, The Republican/TNS)

What the science says about PFAS

Commonly used to make items water resistant or nonstick, PFAS are found in a wide range of products, from food packaging to clothing. Companies began using them in the 1940s.

They do not break down easily, giving them the moniker “forever chemicals.” They are water soluble, making them commonly found in the environment.

In 2020, MassDEP regulated the combination of six PFAS compounds, known as “PFAS6″ at a level of 20 parts per trillion to be considered a safe level of exposure for drinking water. That’s the equivalent of one drop of water in an Olympic-sized swimming pool. It’s a stricter limit than the federal advisory, but the EPA is considering changes to reduce the federal limit.

Human exposure is common: In the U.S., the majority of people have it in their blood, according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. At certain levels, it is linked to harmful health impacts.

Exposure may weaken the immune system, increase the risk for cancers including prostate, kidney, and testicular cancers, interfere with hormones and impact child development, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. There is some evidence, like a study on zebrafish, showing that PFAS exposure can be “multigenerational,” or passed down.

PFOA — a PFAS chemical that was commonly used in firefighting foam — is carcinogenic to humans, the International Agency for Research on Cancer, part of the World Health Organization, concluded last year. The group decided PFOS, another chemical in fire fighting foam, is possibly carcinogenic to people.

Those two PFAS chemicals are the most commonly studied, but PFAS is an umbrella with thousands of compounds underneath it.

Scientists are working to learn more about the health impacts.

Katherine Reeves, professor of epidemiology at UMass Amherst, is researching possible links between PFAS and breast cancer. She’s studying breast tissue samples from the Susan G. Komen Tissue Bank and their corresponding PFAS blood levels to see if markers of breast cancer risk are associated with PFAS.

“I think it’s very important that we understand how these chemicals are impacting our health, because we’re really not in control of our exposure largely,” Reeves said.

In general, research in labs and on animals points to harmful effects from PFAS on breast tissue, she said. For links between PFAS and cancers more broadly, there’s a lot of interest in studying it, but it’s difficult to research. While it will take years of more research to know, she said, “you have enough evidence to suggest that it might be harmful, so we should probably avoid it.”

What’s at the heart of residents’ health concerns?

Kelly Cooley grew up on the north side of Westfield, near Barnes. A high rate of breast cancer in women in her family — including herself, her mother and sister — makes her wonder about a possible link to the city’s drinking water before it was filtered for PFAS.

In the 1980s, she moved to a home bordering the base on East Mountain Road where she raised her children.

In 2017, Cooley’s daughter, Erin, was diagnosed with an aggressive stage three breast cancer. For 18 months, she underwent treatment, including chemotherapy and radiation.

“She fought really hard, but it just kept spreading and spreading,” Cooley said.

Erin died five years ago at the age of 37.

After having multiple cases of breast cancer in her family, Cooley, Erin and other relatives underwent genetic testing to see if the disease was hereditary. “None of us carry the gene,” Cooley said.

Cooley wonders if the city’s drinking water played a part. She can’t know for sure, “but you think about it,” she said.

When she talks with her neighbors and friends in Westfield, the word “cancer” often comes up. Neighbors, friends, pets — many have puzzling cases. Her sister and a neighbor both had the same rare form of kidney cancer, she said. Cooley now hopes to see more research done to answer questions for the Westfield community.

Since Erin’s death, she has moved with her two grandchildren to another part of Westfield. She now has a reverse osmosis system to filter out PFAS, a system that works by using pressurized water to force contaminants, including PFAS compounds, through a semipermeable membrane. “It’s peace of mind,” she said.

Cooley is not the only one who wonders about the city’s water and their community’s health.

John Lucey, who lives off East Mountain Road, said he believes there have been 16 cases of cancer in his neighborhood over the years.

“We’ve been drinking bottled water for seven years,” he said.

The state looked into some cancer rates in the city. Between 2004 and 2013, rates of three cancers in Westfield — kidney, prostate and testicular — were found to be comparable to the state average, according to a 2019 Bureau of Environmental Health screening the city requested. Birth weights during that period were low, according to a letter about the screening sent to the city.

Another neighbor, Jim Duggan, has lived off East Mountain Road since 1985. He participated in a study several years ago that selected people from his neighborhood to give blood samples to test for PFAS.

He was told that as a group, the neighbors’ levels were “higher than normal.” Duggan said he wished he received individualized results.

Hundreds of Westfield residents who drank city water before it was filtered for PFAS have higher than average levels of some PFAS chemicals in their blood. That’s according to an analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

The agencies analyzed 450 people’s blood samples from 247 homes north of the Westfield River, where the air base is located. The average level of one PFAS chemical in the Westfield group’s blood was 3.4 times the national average, the agencies’ 2021 report said. Levels of two PFAS chemicals that used to be in firefighting foam and were detected in city water were at levels higher than national average in the Westfield residents’ blood.

Nicoll Vincent, owns a pet grooming business on Southwick Road in Westfield. She has noticed a high number of animals and owners with tumors and unusual cancers that have been to her shop over the years.

“I was disappointed the city only wanted to focus on the north end,” said Vincent, referring to various tests that have been done on residents on the northside of Westfield. “It makes sense since those wells were shut down for contamination, but there needs to be better focus on the south side of Westfield regarding PFAS testing.”

Babinski, a former city councilor, has lived in the city’s north end for more than 50 years. Some in the city are worried and blame every illness they have on the contamination, while others scoff and say “who cares,” she said. “I’m somewhere in the middle, I think.”

She has a minor thyroid problem, which she believes could be related to PFAS. While she’s not particularly worried about a link, she understands why neighbors might be. “I think people are justified in being concerned.”

Not all Westfield residents are worried, though.

Keith Anderson said he is not concerned about the water because of the city’s filtration system.

How Westfield treats its water

Residents of Westfield get their drinking water from eight wells and one reservoir. PFAS have been found in six of the city’s wells and all either have filtration already or are in the process of getting a treatment center. The drinking water meets state standards, according to the Department of Public Works.

The chemicals have not been detected in the reservoir, said Heather Stayton, the systems engineer for the city’s Department of Public Works.

Customers are more likely to get water from wells closer to their homes, but not exclusively, according to Stayton. “It’s one interconnected system,” she said. That’s a benefit when the city finds contaminants like PFAS in one water source, like a well, and it’s able to turn it off and draw from elsewhere while it addresses the problem, she said.

Water tests reported to the state in the last year show that before filtration, some water sources have a high level of the six PFAS chemicals the state regulates. But after the water is treated, tests do not detect the chemicals in it. In 2022, levels in the city’s drinking water were also below the state limit, according to the city’s water quality report.

In 2020, the city built the Owen District Water Treatment Plant to filter out PFAS from two wells on Westfield’s north side — wells where PFAS were originally detected back in 2013. A similar facility, the Dry Bridge Road Water Treatment Plant, is under construction. It will clean PFAS in water from two wells that are not being used until the project is done.

Each treatment plant contains large vessels that filter the water through granular activated carbon. Stayton said that the four 40,000-pound GAC vessels at the Owen District Road Water Treatment Plant can process millions of gallons of water per day.

The carbon filters have cracks and crevices that PFAS stick to, Stayton said.

The filters don’t last forever. Eventually, the spent carbon is removed and replaced, said Brenda Lopez, the head treatment operator.

As a city that took major action against PFAS contamination, the Westfield Department of Public Works is often asked to speak at industry conferences and to give tours of their facilities, Stayton said.

Questions linger in the community, though. “I still have folks asking me casually all the time, ‘Is my water safe to drink?’” Stayton said. “We go above and beyond that to make sure we are meeting all the state and local standards.”

Stayton and her colleagues drink it. “We know the water coming from our tap is good water,” she said.

Purifying PFAS from the city’s water has been expensive. “It’s in the multiple tens of millions of dollars that we have spent and are in the process of spending,” Stayton said.

The military has chipped in. Several years ago, the Air Force agreed to give the city $1.3 million to put toward PFAS water filtration.

As PFAS has become a nationwide problem, more funding opportunities have emerged. The city has applied for every reimbursement and grant possible, Stayton said.

While helpful, grants do not come close to covering the city’s remediation costs. “When you’ve spent multiple millions of dollars on a project, and a grant caps out at $500,000, it’s a good piece, and we certainly are pursuing those diligently, but it takes a lot of those in order to reimburse the costs that we’ve already put out.”

Citing pending litigation, Mayor Michael McCabe said he can’t comment on the issue, including on how much the city has spent on filtering PFAS out of the water.

“I am going to hold off on commenting until our litigation is completed,” he wrote in an email. “I do not want to adversely affect the outcome,” he added.

Westfield filed a federal lawsuit in 2018 against the firefighting foam chemical manufacturers 3M, Chemguard and Tyco Fire Products. That litigation is now part of 7,000 suits against the companies that have been grouped together in the U.S. District Court in South Carolina.

Individuals are also seeking recourse through the court system. The Downs Law Group, a Florida firm, is representing a few hundred people in PFAS claims, including several from Westfield as part of the multidistrict litigation, according to attorney Alexander Blume.

It will likely be a while until individuals could see a payout, Blume said. “My humble opinion is, it’s years. Not a year, years,” he said. “Which is hard — you see victim suffering, like Kristen and all our other clients — that there’s no redress faster.”

While Mello has been an activist regarding PFAS for years, she long brushed off the idea of getting involved in a lawsuit.

“I kept telling all the lawyers to go away because I didn’t want to sue the city,” she said, “When you sue us we pay. … The city of Westfield is us.”

Mello is working with the law firm to file an individual complaint in the federal litigation against the companies.

“They knew about the toxicity before I was born,” she said. “It’s not like somebody found out last Tuesday and they didn’t tell us soon enough.”

©2024 Advance Local Media LLC.

Visit masslive.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.