U.S.

‘No prescription needed’: Inside a White House clinic’s ‘systemic problems’

The Washington Post February 16, 2024

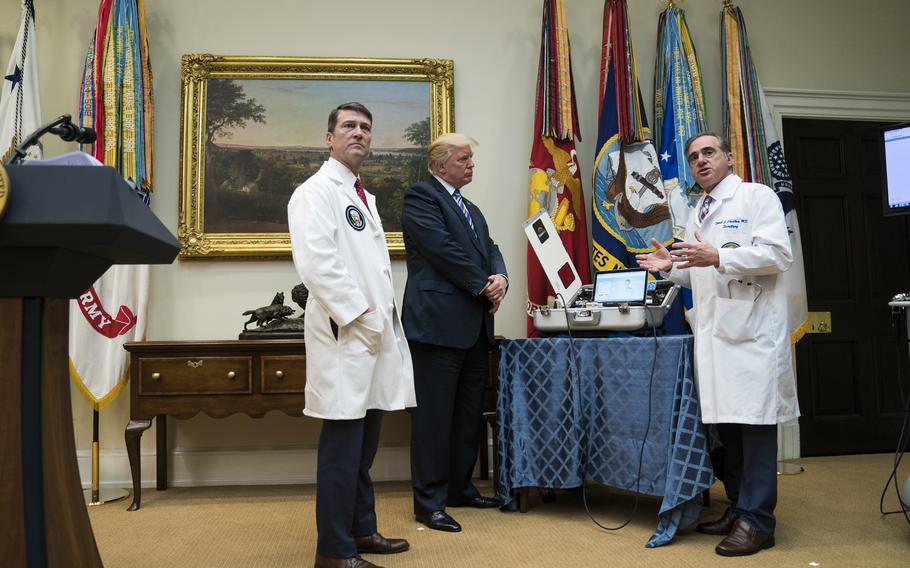

Ronny Jackson, left, then White House physician, and President Donald Trump at the White House in 2017. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

When Omarosa Manigault Newman wrenched her ankle while rushing to join a motorcade in January 2017, the Trump aide and former reality TV star sought help from the White House Medical Unit — a military-run clinic that promised free, on-demand care to senior officials.

But Manigault Newman quickly realized the clinic went beyond standard procedures.

“They would give out anything, right from the bottle, no prescription needed,” Manigault Newman recounted in her memoir “Unhinged.”

Now, the Pentagon has confirmed many aspects of what Manigault Newman said was an open secret among senior officials.

A long-awaited inspector general’s report released last month faulted previous White House medical teams for widely dispensing sedatives and stimulants, failing to maintain records on potent drugs including fentanyl, providing care to potentially hundreds of ineligible White House staff and contractors, and flouting other federal regulations.

“We concluded that all phases of the White House Medical Unit’s pharmacy operations had severe and systemic problems,” the report concluded, adding that the challenges threatened the unit’s primary mission — to keep the president and vice president healthy and safe.

The inspector general’s report sparked significant public alarm. But a Washington Post review found problems with the unit’s conduct were even more pronounced than the Pentagon’s latest findings, according to administration documents and interviews with former White House staffers and medical unit members, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss private conversations and internal procedures.

Four former members of the White House Medical Unit confirmed that in both the Trump and Obama White Houses, the team passed out sedatives such as Ambien and stimulants such as Provigil without proper prescriptions, provided complimentary medical equipment and imaging to ineligible staffers, and used aliases in electronic health records to disguise the patients’ identities and deliver free care in cases where the recipients wouldn’t be eligible.

Former staffers said those practices were shaped by Ronny Jackson, an emergency medicine physician who led the team under President Barack Obama, continued to exert control over it as President Donald Trump’s personal doctor, and ultimately spent nearly 14 years in the White House. Now a Republican congressman, Jackson used his proximity to both presidents to build influence by dispensing medical care and drugs without proper procedures, the staffers said — conduct that earned him nicknames such as “Candyman” or “Dr. Feelgood,” according to a whistleblower complaint to Congress in 2018.

According to Jackson’s own portrayal, he worked as a personal doctor to dozens of officials, providing whatever they needed and whenever they needed it.

“It was full-blown, over-the-top, concierge executive medicine, and we did it better than anybody else on the planet. As a result, everyone treated me and my team very well,” Jackson wrote in his 2022 memoir, “Holding the Line,” where he described how his practices helped him win favor with both Obama and Trump. “The entire medical unit had a special place in the hierarchy of the White House. … I had a lot more to offer than any doctor they had ever had before, and they needed me close by.”

The congressman and his allies have dismissed criticism about his work in the White House as politically motivated, anti-Trump attacks — a message his office echoed recently, alleging in an email that the inspector general is helping conduct a “hit job directed at the healthiest President of all time.” Jackson’s office also argued that he should not be blamed for events that took place after December 2014, when he stepped down as the medical unit’s director while remaining in the influential role of physician to the president, and said that White House lawyers and senior Defense Department officials were aware of the unit’s practices, contrary to the inspector general’s findings.

In an interview on Capitol Hill last month, Jackson said White House lawyers signed off on his medical decisions. “People were getting the care that was authorized,” Jackson told a reporter, adding that the medical team played a particularly important role on trips abroad.

He added that his team prescribed narcotics “less than five times” across his tenure, such as cases where someone broke a bone. The unit staffers who spoke to The Post also said that fentanyl, while improperly tracked in the clinic’s records — a finding of the Pentagon report that has drawn particular attention since its publication — was never actually prescribed to their knowledge. Instead, it was kept on hand for extreme emergencies — such as a White House fence jumper impaling themselves on a spike.

“The accusations that … we prescribed fentanyl and morphine to patients is absolutely absurd,” Jackson said. “No one has ever prescribed fentanyl to a patient. And yes, we ordered fentanyl.”

Jackson told reporters in 2018 that he had prescribed Ambien to Trump while traveling, and two former staffers said that Obama also received sleep aids on trips. But there’s no evidence in the reports, or from staffers who spoke to The Post, that either president abused Jackson’s ready access to the medication.

President Biden brought on Kevin O’Connor as his personal physician in 2021 — reprising the role he played for Biden during the Obama administration. O’Connor, whom Jackson has publicly demeaned and portrayed as a rival, left the White House during the Trump administration. The White House did not make O’Connor available for an interview and referred questions about the medical unit to the Pentagon, which oversees the team’s operations. The Obama Foundation did not respond to questions about the medical unit’s operations in his administration.

The Pentagon said in a statement that “new personnel and reforms were put in place” in the medical unit under Biden’s presidency, citing new leadership but declining to specify other changes. The Defense Department also has committed to developing safeguards around prescriptions, patient eligibility and other problems identified by the inspector general.

But Jackson’s former colleagues say they remain concerned about his conduct and proximity to power. The longtime military doctor is arguably the most prominent voice who has vouched for the health and mental acuity of Trump as he seeks to return to the White House. The new Pentagon report also arrives amid widespread questions about the 81-year-old Biden’s own fitness to serve, placing new scrutiny on the White House medical team trusted with his health.

“This isn’t a partisan issue — it’s a Ronny Jackson issue,” said a former colleague in the White House unit, lamenting that Jackson disregarded medical norms to satisfy powerful people. “It was bad under Obama, and it got worse under Trump. … If Trump empowers him again, I don’t know what he’ll do.”

Ronny Jackson spent nearly 14 years in the White House. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

Winning fans in the White House

Jackson’s path to the White House began in West Texas, where he was the son of a homemaker and an electrician who sometimes struggled to make ends meet.

In his memoir, he describes his decision to attend junior college and later Texas A&M University at Galveston over the objections of his father, who urged Jackson to work full time in an oil field instead.

Scrounging for money for medical school, Jackson won a scholarship from the Navy that paid his tuition in exchange for four years of service, where he fell in love with military life, he has said. While serving in Iraq — supporting a shock trauma team working to save patients hit by IEDs — a mentor nominated him for an opening as a White House doctor.

Jackson arrived at the White House in 2006, stepping into arguably the most prestigious post in military medicine. By 2010, he was running the entire unit, which had more than two dozen health workers stationed across several clinics in the White House, the neighboring Eisenhower Executive Office Building and other locations.

Under Pentagon rules, the medical unit’s primary mission was to treat the president and vice president, their families and military personnel. The unit also could provide emergency care if something happened on the White House grounds. While some other senior officials could use the unit’s clinics, they needed to reimburse the military health system for those services.

After taking charge of the unit, Jackson dramatically broadened its mission with a unique theory: “care-by-proxy,” arguing that providing regular, complimentary treatment to officials close to the president was necessary for the president to do his job. Jackson also oversaw an expansion of the unit, which reached more than 60 staffers by 2019 — triple its size when he arrived.

“I was eventually taking care of the entire West Wing, East Wing, and everyone who supported them,” Jackson wrote in his memoir. “The First Family, most of the cabinet secretaries, all the assistants to the president, the chief of staff, the national security advisor, the press secretary, the Secret Service, the White House staff, Air Force One, Camp David, the presidential helicopter squadron, the White House Communications Agency, the White House Mess, the military aides, and anyone else who worked in the White House were all my patients.”

The decision to treat hundreds of people also had another benefit for the ambitious Jackson: endearing him to officials across multiple administrations. Some of those officials have said they were wowed by Jackson’s commitment to caring for people beyond the White House, including their relatives and friends.

“During his off time, Dr. Jackson went to the hospital … [to ensure] that our friend’s father was getting the care that he needed,” former Obama communications official Dan Pfeiffer said on a 2018 episode of the “Pod Save America” podcast. “That is so far beyond the duties of the White House doctor.”

Jackson also grew close to Obama, who picked him as his personal physician aboard a 2013 Air Force One flight, promoted him to rear admiral in 2016 and included him in an intimate gathering at his residence on his final night in the White House in January 2017. Obama also expected the doctor — who had told the president and colleagues that he was resigning — to leave the White House with him the following day.

But Jackson, according to his memoir, was a lifelong conservative who kept his views to himself during the Obama administration, was privately thrilled by Trump’s election and was persuaded by the incoming team to stay on, a decision he says he conveyed to Obama on the morning of Inauguration Day 2017, shocking the outgoing president.

White House Medical Unit staff have described the thrill of working in the building — and the difficulty of saying goodbye.

“The proximity to power can be as intoxicating as power itself,” Eleanor “Connie” Mariano, a former White House physician to Presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, wrote in her memoir, “The White House Doctor.”

In his own memoir, Jackson describes becoming the daily companion of Trump, working out of an office directly below the president’s bedroom and greeting Trump every morning before walking him to the West Wing. The nation’s new leader came to rely on his physician for private policy advice, especially because Jackson was often the first person he saw each day. For instance, Jackson in his memoir writes that he urged Trump to ban transgender people from serving in the military — a decision that he said Trump announced the next day, befuddling Pentagon officials who could not identify the military experts that Trump claimed to have consulted.

Former medical unit staff told The Post that Jackson’s behavior worsened under Trump, saying that the longtime military official was quicker to berate staff and insist that senior Trump officials get access to whatever care they wanted.

Manigault Newman said she stands by her assessment of the unit in her memoir, which describes easy access to prescription drugs and other care granted to her and other senior officials.

“I was taken aback by how very freely they were dispersing some of the most powerful and addictive pain medication in the program,” she said in a text to The Post.

Jackson also become the most important public champion of the president’s competence, planning a comprehensive series of medical and cognitive tests in January 2018 that he believed would address unfair doubts about Trump’s physical and mental health.

“His health is excellent right now,” Jackson told reporters after the tests. “The President is mentally very, very sharp. … I think he will remain fit for duty for the remainder of this term and even for the remainder of another term, if he’s elected.”

Some physicians and reporters raised questions about whether Jackson’s assessment was correct or credible — keying on Jackson’s praise for Trump’s “incredibly good genes” and his joke that the president could “live to be 200 years old” if he only ate healthier. But at the time, they were rebuked by former Obama officials who vouched for Jackson as an apolitical operator.

“In my experience, he was very good guy and straight shooter,” David Axelrod, one of Obama’s top advisers, wrote on social media after Jackson’s 2018 briefing.

Ronny Jackson speaks to reporters at the White House in 2018. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

‘You cannot confirm this guy’

Two months after Jackson’s glowing endorsement, Trump tapped his physician to run the Department of Veterans Affairs, the nation’s $90 billion health system that cares for millions of military veterans and their families.

The decision would change the arc of Jackson’s career and bring new scrutiny to his team.

As a key Senate hearing on his nomination approached in April, the panel’s top Democrat said he received an urgent call. A uniformed officer who had worked with Jackson wanted to warn Congress that he was unfit for the job, Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.) later recounted.

“‘You cannot confirm this guy,’” the officer said, according to Tester’s memoir “Grounded.” The officer warned that while the president’s physician had charmed Trump, he had been a vindictive leader, reckless with prescriptions, and alleged that he had consumed alcohol on the job.

Tester’s office later spoke with 22 other current and former colleagues of Jackson who offered similar testimonies. On April 25, Tester circulated a two-page memo summarizing their claims, including an eye-popping allegation that “Jackson got drunk and wrecked a government vehicle”; Jackson withdrew his nomination the following day.

“He would’ve done a great job,” Trump lamented in an interview on “Fox & Friends” that morning. “These are all false accusations. These are false. They’re trying to destroy a man.”

The failed VA nomination did not end Jackson’s political career, though it did push him closer to Trump. The president named Jackson his chief medical adviser in 2019, supported his long-shot candidacy for Congress in 2020 and even dispatched several of his top political advisers to help Jackson when it appeared his campaign was flailing.

Jackson also embraced Trump on the campaign trail. Once Obama’s physician and friend, he now railed against his policies and mocked Biden’s cognitive health — prompting a swift, private rebuke from his most famous former patient.

“I expect better, and I hope upon reflection that you will expect more of yourself in the future,” Obama wrote in an email to Jackson.

Jackson sailed to victory in November 2020, winning his congressional seat by a 60-point margin. Days into his new role as a congressman in March 2021, the Pentagon released its inspector general report into the whistleblower claims first surfaced by Tester three years earlier. Investigators could not verify allegations that Jackson “got drunk and wrecked a government vehicle,” and some staff praised his high standards for performance.

But the Pentagon watchdog did conclude that Jackson had mistreated his colleagues and subordinates; of the 60 witnesses who had worked closely with Jackson, 56 said they were aware that Jackson’s behavior toward staff involved “yelling, screeching, rage, tantrums, and meltdowns.” The report also cited episodes where Jackson discussed a female staff member’s anatomy, drank on the job and took Ambien while he was supposed to be on call to the president.

The report concluded that Jackson continued to play a major role in the unit after he stepped down as director in 2014, when he was replaced by his former deputy Keith Bass; for instance, Jackson continued to sign employee evaluations until 2017, the Pentagon said, and staff told the inspector general he continued to bully them. Bass, who led the unit through 2019 and now serves as medical center director for West Texas VA Health Care System, did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

The Navy secretary should “take appropriate action regarding [rear admiral] Jackson,” the watchdog recommended.

The Pentagon declined to comment on whether it had penalized Jackson, who retired from the Navy in December 2019, ahead of his congressional campaign. The Navy did take an unspecified “administrative action” against Jackson after the 2021 inspector general report substantiated allegations against him, a Defense Department official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss a personnel matter.

In his memoir, Jackson says he turned down an opportunity to comment for the report. He also claimed that the probe would have gone away if he hadn’t entered politics and aligned himself with Trump.

“This was happening because I am a perceived threat to the Biden administration and because a few political appointees in the Department of Defense want to make a name for themselves,” he wrote.

Meanwhile, the Pentagon watchdog announced that it had opened a second probe into the practices of the whole medical unit. Investigators interviewed more than 120 officials, including staffers who worked in the unit across a decade, and reviewed hundreds of documents before sending a draft of its findings to the White House military office — which oversees the medical team — in May 2020.

Different standards for care

More than three years after it was delivered to the White House, the report was released last month. It’s unclear what caused the delay, although Trump in April 2020 ousted the Pentagon inspector general who was overseeing the report and other investigations.

The Pentagon didn’t respond to questions about the delay. The White House referred questions to the Pentagon.

Unlike the Pentagon’s earlier examination of Jackson’s behavior, the agency’s new report does not mention any individuals by name, occasionally referring to the “physician to the president” — Jackson’s title at the time — or decisions made by the unit’s broader leadership. But the 80-page report paints a portrait of a medical team that often disregarded rules intended to protect patients.

For instance, the watchdog concludes that the White House medical team repeatedly flouted pharmacy safety standards, including by handing out controlled substances such as Ambien or Provigil without verifying a patient’s identity as Pentagon rules required. Former team members told The Post that Jackson helped institute a culture where such behavior was normalized.

The Pentagon further blamed the team for writing incomplete prescriptions that were missing information required by the Drug Enforcement Administration, as well as years of shoddy record-keeping.

“These records frequently contained errors in the medication counts, illegible text, or crossed out text,” the watchdog concluded, including photographs of sloppy paperwork.

The Pentagon also took a dim view of Jackson’s broadening of care, saying that senior military officials either denied knowledge of “care by proxy” or stated that it was not an approved practice. As many as 20 patients per week were ineligible for the care that they received free from the White House Medical Unit, the report concluded, and even the most senior presidential aides should have repaid the military health system if their care was not waived. The watchdog added that it could find no evidence that those patients’ costs of care had been appropriately waived.

Former medical staff also told the Pentagon that some senior presidential appointees wrongly received free specialty care and even surgery at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center — under aliases assigned by White House Medical Unit leaders, disguising their identities. The staffers who spoke to The Post repeated those claims. The Pentagon watchdog said it was unable to confirm those allegations because alias accounts could not be tracked or audited.

The inspector general’s report identifies multiple examples of how favoritism shaped the White House team’s choices. For instance, “medical care was prioritized by seniority rather than medical need, which increased the risk to the health and safety of non‑executive medicine patients,” the report found, a conclusion echoed by former members of the White House Medical Unit.

“It was very clear from Day 1 that people were treated differently based on how powerful they were perceived to be,” said a former member of the team.

The White House team also refused to order low-cost generic drugs because their patients preferred to use brand names such as Ambien — which was about 174 times more expensive than its generic equivalent. That decision squandered taxpayers’ dollars, the Pentagon concluded; the unit wasted about $100,000 just on buying Ambien, Provigil and sleeping drug Sonata between 2018 and 2019, rather than their cheaper generic equivalents. The decision to buy costly name brand drugs also flouted federal regulations that instruct military health officers to purchase low-cost generics when available, the report found.

The watchdog also rebuked the medical team for maintaining self‑service, open‑access containers where White House officials and visitors could retrieve common over‑the‑counter painkillers, cough drops and other medications.

While many private workplaces offer similar cabinets, “the Navy Manual of the Medical Department expressly prohibits this practice,” the Pentagon wrote.

Today, those medication cabinets have been removed, two officials told The Post — one of the most visible examples of how the new Pentagon report has resonated at the White House.

Other changes are harder to discern. Defense Department officials said that they would implement the inspector general’s most recent recommendations, such as adopting tighter controls over prescriptions and updating rules on who can access the White House Medical Unit’s services.

It’s also not clear what professional consequences Jackson has suffered following multiple Pentagon investigations, whistleblower complaints and other actions by watchdogs, such as Public Citizen’s call for Virginia’s medical board to investigate Jackson’s practices. Jackson’s Virginia medical license expired in May 2020, and his Florida medical license that allows him to practice at military facilities is set to expire next year, according to a review of licensure records.

Jackson’s medical credentials came to the forefront last year, when he attempted to treat a teenage girl who was having a seizure at a Texas rodeo, sparking a confrontation with sheriff’s deputies and emergency medical personnel who said he was belligerent and appeared intoxicated. He is not licensed in the state. Jackson’s staff at the time defended his conduct, saying that he would “not apologize for sparing no effort to help in a medical emergency.”

Jackson’s office did not respond to questions about the Navy’s administrative action or his medical licenses.

As a two-term congressman, Jackson has taken a prominent role in backing Trump’s latest campaign — making appearances on Fox News and other conservative outlets, defending Trump in congressional hearings and attacking the sitting president on medical grounds. Jackson has repeatedly called on Biden to take a cognitive test, saying it is necessary to address the same sort of questions that dogged Trump for years.

About three-quarters of voters — including half of Democrats — have concerns about the 81-year-old president’s mental and physical health, according to an NBC News poll released in early February. In contrast, about half of voters have concerns about the 77-year-old Trump’s health, and in last month’s interview, Jackson insisted that there was nothing to fear.

“I have no concerns whatsoever. President Donald Trump is in great physical condition. He’s sharp as a tack,” Jackson said. “He proves that on a day-to-day basis.”

Aaron Schaffer, Bishop Sand and Lisa Rein contributed to this report.