Some 383 Afghans wait to board an Airbus 340 on Sept. 24, 2021, as part of private rescue mission Operation Bella, named for the daughter of Jason Kander of Kansas City. (Courtesy Jason Kander for The Kansas City Star/TNS)

KANSAS CITY, Mo. (Tribune News Service) — Inside the ballroom, 383 Afghan men, women and children — fake guests invited to a fake wedding — waited in anxious hope that the ruse might work and they could escape the country with their lives.

Meanwhile, just beyond their walls, armed Taliban fighters looking to kill or imprison them searched the streets of Mazar-e-Sharif. Afghanistan had fallen. It was September 2021, only three weeks after the United States military on Aug. 30 had pulled out of 20 years of war. Images of desperate citizens clinging to and falling from the wheels of planes fleeing Kabul remained indelible. The Taliban were now in control.

Seven thousand miles away in Kansas City, Jason Kander — a former Army intelligence officer and former Missouri secretary of state who had turned private citizen — sweated out what last week he called “the craziest thing, the biggest thing and the most important thing I have ever done.”

Code name: Operation Bella, a private Afghan rescue mission initiated by Kander and named after his then-infant daughter. Details of its safe houses and checkpoints, of a chartered aircraft escaping Taliban gunfire, are only now being revealed.

On Thursday evening, Kander, 42, and 36-year-old Rahim Rauffi, whose rescue triggered the operation, are scheduled to discuss the rescue at a fundraising event for Jewish Vocational Service. In June, JVS, which aided in some of the operation, relocated Rauffi, his wife, four children and eight relatives as refugees to Kansas City.

“To be honest,” Rauffi told The Star, “without Jason, without his support, it (escaping) was just a dream. Impossible.”

Photo of Taliban soldier just outside the hotel in Mazar-e-Sharif where 383 people hid before escaping Afghanistan as part of Operation Bella. (Courtesy Jason Kander for The Kansas City Star/TNS)

Everywhere are Taliban

In broad strokes, Kander told The Star, the events unfurled like this:

A former Army captain, Kander had served in Afghanistan as a military intelligence officer for roughly four months, October 2006 to February 2007. His translator then was Salam Rauffi, an American-born Afghan living in Kabul. They stayed in touch.

When, in August 2021, the U.S. military withdrew, leaving behind Afghan allies whom the Taliban would view as collaborators, Kander contacted his former translator to see if he needed help. Being American-born, Salam Rauffi did not, but he had a nephew who did.

Rahim Rauffi had been a banker in Kabul, handling payroll for several international organizations, including the United Nations, military compounds and the U.S. Embassy. He had lists of Afghans who worked with them. The Taliban wanted those names to such a degree that, by 2016, the Taliban tried to kidnap Rauffi. They threatened his life and beat Najim, one of his two younger brothers.

Rauffi fled to India with not just his wife and children, but also with his mother, two brothers and their families.

“I never left anyone behind,” Rauffi said. He felt responsible for placing his extended family at risk. “Because of me they are in trouble.”

In India, his family ran a hotel, and Rauffi worked as a hospital interpreter until the strain triggered two heart attacks. COVID-19 then hit. The nation locked down.

“I was not able to support my family there anymore,” Rauffi said. In early August 2021, they returned to Kabul, thinking that, after nearly six years, maybe the danger had passed. That month, the Taliban surged back into power.

“I was thinking, ‘What will happen now?’” Rauffi said. “There is no elected government. Taliban is everything. Everywhere is Taliban. Because of me, my entire family was in danger.”

He worried most of all about his wife, Rahima, and daughters SanaTamkin, Hadia and Mahdia, fearful of the futures they’d have under Taliban rule.

Kander, using information from his former interpreter, contacted Rauffi. They had never met, never spoken. Rauffi’s was a leap of faith.

“I was looking for a very small green light for saving our lives,” he said.

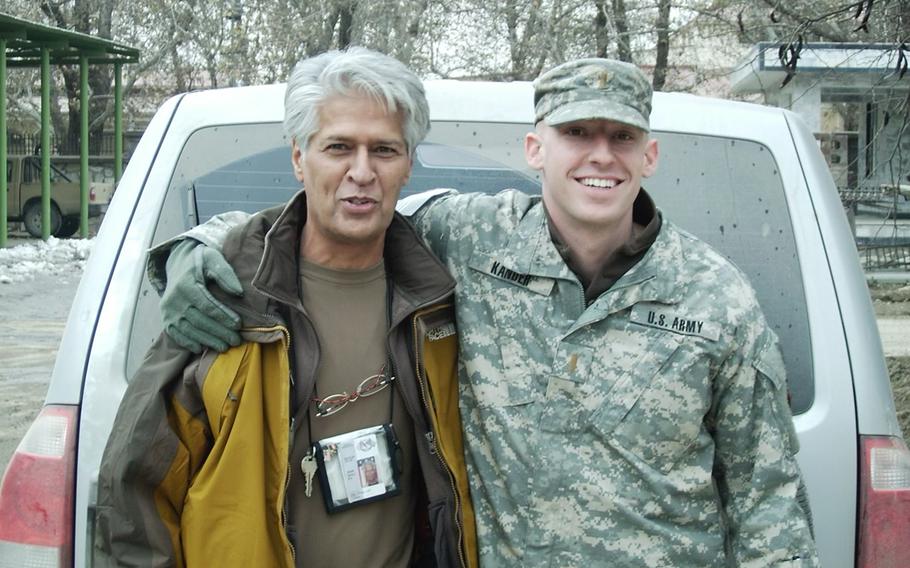

Jason Kander, right, with interpreter Salam Rauffi in Afghanistan in 2007. (Courtesy Jason Kander for The Kansas City Star/TNS)

Back in the U.S., Kander said, he was met with “chaos.”

“I had no idea what to do,” Kander said. “I start calling everybody I know from intelligence school, to the Intelligence Corps, to regular Army folks to political folks. … There was no way to get hold of anybody.”

Kander told Rauffi, at one point, that he could possibly get him and his own immediate family out.

“To his credit,” Kander said, “he said, ‘Everybody is in danger because of me. It has to be all of us.’”

The more Kander worked to help Rauffi, the more he heard from other veterans like himself looking to rescue Afghan allies who had been left behind. Slowly, a coalition began to build.

Kander started a GoFundMe site to raise money to help trapped Afghans, with Jewish Vocational Service agreeing to handle the incoming funds. Back in 1989, it was Jewish Vocational Service that had helped relocate the family of Kander’s wife as Jewish refugees from Soviet Ukraine. Diana, whose maiden name was Kagan, was 8 then, arriving with her family and grandmother, also named Bella.

Hundreds of thousands of dollars poured in from across the country. The operation, in the end, would cost nearly $3 million.

Unbeknownst to Rauffi, the secret plan to rescue his family quickly grew to a plan to rescue not just one, but two, then 10, then 20, then ultimately 75 families — or as Kander called them “383 souls.” To pull it off, Kander and colleagues had to make sure that none of the families knew of one another.

“We couldn’t tell them,” Kander said, “because if one got captured, the whole thing could be lost.”

Rahim Rauffi and his family in hiding in Kabul in September 2021, only days after Afghanistan fell to the Taliban. The photo was taken to help U.S. military forces identify them should they be chosen for a military-led escape. (Courtesy Jason Kander for The Kansas City Star/TNS)

‘My kids saved me’

What became obvious: Flights out of Kabul were a no go. The families had to move. The city of Mazar-e-Sharif (population 500,000) was chosen. Whereas the Taliban were derived mostly of Afghans from the Pashtun east and south, Mazar-e-Sharif in the north, close to the Uzbekistan border, had significant populations of Uzbeks and Tajiks. The Taliban were taking control of every city, but still it was considered a safer bet.

The next step was a 15-hour, circuitous trip northwest from Kabul using what, if Rauffi was lucky, was hopefully not a completely outdated intelligence map, to help the family bypass Taliban checkpoints. Rauffi and 11 relatives loaded into two rented minivans.

If stopped and discovered as a collaborator, Rauffi had little doubt about what might happen.

“They are just shooting people on the road, in cars, anywhere,” he said. ”They don’t care. No judgment. No judgment. Any of them. They can do whatever they want.”

For a while all was good. Then at 2:30 a.m., a checkpoint. Armed Taliban fighters, their faces covered, approached Rauffi’s van.

“They’re just shouting, ‘Come out! Come out!” Rauffi said. As he did, he slipped his cellphone, still full of incriminating names and numbers, to his mother. The family had concocted a cover story: They are going to Mazar-e- Sharif for a funeral, they told the soldiers. It’s their mother’s sister. The ceremony is in the morning.

The fighters continued questioning Rauffi, searching him.

“Then my kids, they start shouting and crying,” Rauffi said.

Fifteen hours passed before Kander heard from Rauffi again.

“Rahim told me later,” Kander said. “He said, ‘My kids saved me because all the noise the kids were making, and freaking out, I guess the Taliban, as a result, just bought the cover story.”

They let them pass.

Once the family made it to Mazar-e- Sharif, Kander and Rauffi remained in contact day and night for the next three weeks. They grew close. They discussed their children, their families. Kander’s infant daughter Bella and Rauffi’s daughter SanaTamkin shared the same birthday, Sept. 25.

For safety, the family kept changing locations, often in the dead of night, and still having no idea how large the operation had grown.

“For everybody’s safety,” Kander said, “it worked best if they only knew the minimum they needed to know. So what I told him was, ‘I’m working on something. Then, at some point, I will call you and I will have some place for you to go. Just be ready.’”

Hope can bend under pressure.

“You know when your heart is beating, your hands are shaking, you feel the weakness in your legs?” Rauffi said. ”From the day my country (had) fallen at the hands of Taliban, I had the same feeling. But I was not able to show my real face to my family. I just try to be very strong, to control everything and show them, ‘Hey, everything is OK.”

Farhad, Rahim and Najim Rauffi in Kansas City. The brothers were rescued from Afghanistan through Operation Bella. (Courtesy Jason Kander for The Kansas City Star/TNS)

‘Welcome to the wedding’

On Sept. 21, the call came at 9 a.m. They had three hours to get ready, Kander relayed. One suitcase per person.

“He said I am sending you some information,” Rauffi said. “Go to this location. This is the name. You have to find someone inside. Give them the code.”

Bella.

At first, Kander said, Rauffi seemed confused, concerned.

“I repeated the code word again,” Kander said. “And I said, ‘Like my daughter’s name.’ And I said, ‘Bring your daughters here to America to meet Bella.’ ”

Kander recalls Rauffi laughing in relief. He said OK.

Kander chose to remain reticent regarding who in the city helped coordinate the ruse that followed, except to say, “We paid the hotel very well.”

Inside the location, Rauffi and his family were asked their names. They provided the password and were led to a large banquet room. There, they were shocked to see dozens of other people, soon to grow to 383, and all, like them, carrying luggage. He stood befuddled.

“He called me,” Kander said. “He said, ‘I’m here. What is this?’ I said, ‘Welcome to the wedding.’ ”

The plan became clear. There was no real wedding. No bride. No groom. No music. But that’s the way the room had been booked.

“We catered it like a real wedding,” Kander said. “They ate very well.

If the plan went off perfectly, the 75 families would only have to be there one night, sleeping on the floor behind closed doors and away from the Taliban, which patrolled the streets. One day later, they would have the necessary documents, get on a bus, board a chartered plane in Mazar-e-Sharif and be on their way to freedom through a U.S. air base.

Then their best laid plan went awry.

“The problem is,” Kander said, “you can’t just have people show up at the airport and on a plane. They’re all wanted, first of all. Second, you can’t do it at all if you don’t have landing rights in another country with a visa and cleared flight manifest.”

In other words, refugees need proper documents.

“The way the game worked at that point,” Kander said, “if the Taliban was looking for you, and they found you, they could do whatever they wanted. They could shoot you in your head. They could send you to prison, whatever.

“But if they do not find you until you present inside the airport and you’re on a visa with a cleared flight manifest to another country — on a flight that has landing rights — now if they detain or kill you, it is an international incident because you’re expected in another country.”

Problem was, Kander said, the U.S. at the last minute would not provide the needed documents.

So instead of one day at the hotel, 383 people remained in the ballroom for two days and nights, then a third, with armed Taliban soldiers just outside the hotel. One evacuee snapped a photo of a soldier through a window standing outside only feet away.

Taliban soldiers, at one time, entered an actual wedding in an adjacent ballroom. Afraid that the fake wedding might be discovered, wives, mothers and girls thought quickly. They gathered by the door, knowing that male soldiers, under sharia law, would be reluctant to pass through a group of women. They held their breath. The soldiers went away.

Meanwhile, Kander and his compatriots scrambled to secure a different way out, and found it. Instead of flying to a U.S air base, they would fly to Albania.

On Sept. 24, 2021, 75 families boarded buses outside the hotel and headed toward Mazar-e-Sharif International Airport, with Taliban soldiers checking their documents at every step: before they boarded the bus, off the bus, at the airport, on the tarmac.

“Oh my God. Oh my God,” Rauffi said. “Shaking, sweating, shaking. Here, then 50 meters ahead, another checkpoint, then another checkpoint. They were looking for just one small mistake, anything to stop us.”

Finally, they boarded an Airbus A340. There was no relaxing. Everyone remained silent, Rauffi said. Night had fallen. The jet’s engines whirred. Suddenly, the lights in the entire aircraft went black. Outside went black. No lights on the wings. No lights on the runway.

When the Airbus took off, it shot upward like a fighter jet, banking severely. Only later did Rauffi and others discover the reason.

“Outside, behind the airport,” Rauffi said, “there was a small village that was Taliban. They were shooting at the plane.”

The lights had gone black to make the plane invisible.

Heroes

The Airbus landed hours later in Tibilisi, Georgia, where the group split and boarded two Boeing 727s to Albania. Rauffi and others would stay at a hotel by the seaside for the next two years. In time, the families would make their ways to various countries.

In the U.S., a number of families relocated to St. Louis. Rauffi and his 13 family members — his mother, his two brothers and their families that now included two new children born in Albania — were the only ones who chose to come to Kansas City, to be with the friend who helped save their lives.

“They now live six minutes from our house and they are part of our family,” Kander said. He cares for them and admires them as if they were.

“I have a lot of interest in telling this story,” Kander said. “One of my purposes hasn’t changed. I want — as there’s going to be all these Afghan Americans here now — I want Americans to understand that every Afghan American they meet did something heroic to get here. They may meet them — they may be their waiter or someone else — but they’re one of the greatest heroes they’ve ever met.”

Rahim Rauffi works at Commerce Bank, along with younger brothers Najim and Farhad. Bella Kander, who is now 3, celebrated a joint birthday with SanaTamkin Rauffi, age 10.

Operation Bella led Kander to found a nonprofit, Afghan Rescue Project, which he estimated eventually helped evacuate some 2,100 people. The organization, operated out of Fairfax, Virginia, has since been renamed the American Rescue Project, and works to help people in the midst of emerging international crises.

But it began with one person and an offer to help.

“I think that I, and a lot of other Afghan vets, felt that — as we were watching the Taliban retake the country — a lot of people who we had served with, we were in the situation where our country had made promises to them,” Kander said.

That promise was to help them.

“That, at least to me,” he said, “didn’t feel much different than we had made personal promises to them. I remain heartbroken by the fact that there are so many people to whom we have not been able to keep that promise.”

Celebrating its 75th year, Jewish Vocational Service’s discussion with Kander and Rauffi is scheduled for 6:30 p.m. Feb. 8 at Union Station in the KC Chamber Board Room, 30 W. Pershing Ave. General admission tickets are $25.

©2024 The Kansas City Star.

Visit kansascity.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.