Frances Sharples, a longtime National Academy of Sciences leader who served as a technology adviser in the Clinton White House, lost hundreds of thousands of dollars to scammers. It started with a warning that her identity had been stolen. (Amanda Andrade-Rhoades/for The Washington Post)

Frances Sharples walked through the glass doors of her credit union, ready to make the worst decision of her life.

She had a script from the man promising to save the retirement account she built over decades as a science adviser to the U.S. government, including in the White House.

He told her to transfer more than $600,000 — and to keep her cellphone on so he could listen to her. If anyone asked whether she was put up to it, she was to reply: “No, absolutely not,” according to her hand-scrawled notes. No one did. She handed the clerk the routing number, walked back to her dented 2005 Honda and returned home.

“Now I’m good,” she told herself. “Now, I’m safe.”

The doctorate daughter of a plumber from Queens had made a life advising the federal government on stem cells, new energy technologies and the effects of biological weapons. Despite a history of meticulousness, Sharples was victimized by a global network of online criminals, including a man with a gentle Indian accent who helped make off with much of her life savings.

The government she served for more than four decades is compounding her pain. The Internal Revenue Service told Sharples, 73, she had to pay hefty taxes on the stolen money, which the federal government considers income. Tax specialists said someone in Sharples’ position could face a six-figure bill.

The story of how Sharples was hit twice — first by an international criminal network, then by the U.S. tax code — underscores the nation’s vulnerability to global cybercrime and points to inconsistencies in the treatment of fraud victims, law enforcement and tax experts said.

“It goes against a person’s conscience,” said Ismael Guerra, a retired IRS criminal investigator and revenue agent who independently examined Sharples’ case. “The scammers get away, the government gets its piece, and she gets nothing.”

Current and former law enforcement officials say Sharples, like thousands of others each year, was snagged by global scammers who weaponize technological annoyances of modern life, tactics of telemarketing firms and human vulnerabilities to trip up people who aren’t the stereotypical easy mark.

The experts keep telling her she shouldn’t blame herself.

But she’s a scientist. She has evidence before her. And it’s proved impossible to ignore.

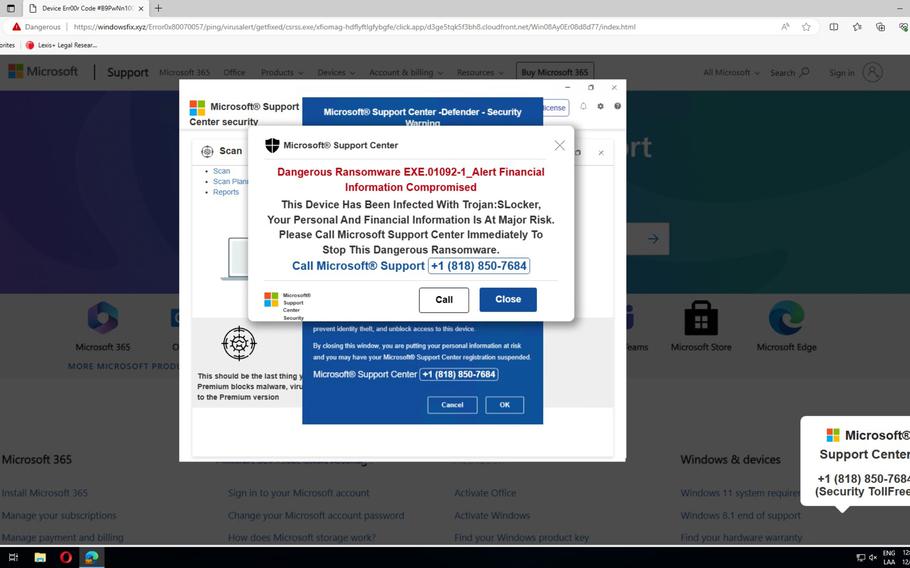

An example of a tech support scam message that pops up on a user’s screen. (Microsoft)

The ‘tech support’ scam

In her home office in February last year, with a sparrow’s nest outside her window and chipmunk figurines on bookshelves behind her, Sharples sat stumped by the Spelling Bee word game on her screen.

She was checking another website for hints, hunting for words to help solve the puzzle, when her computer froze. A giant red sign filled her screen, along with a warning and instructions: Her identity had been stolen. She needed to protect herself by calling Microsoft at the 800 number provided.

A man with a vaguely European accent — she wondered, was it Dutch? — picked up her call, identifying himself as Peter Williams of Microsoft. He said her computer and bank account had been compromised and three attempts had been made to withdraw funds. She needed to act now.

It was a classic opening for a well-worn tactic known as a “tech support” scam. FBI figures show an exponential increase in the amount of losses reported in these scams alone, jumping from $15 million in 2017 to more than $800 million last year.

Scammers funnel victims to malicious websites by promoting tainted search results and online ads, experts said.

Williams installed software on her computer, giving him control. He urged her to call the customer service number on the back of her bank card for help.

The man who answered offered his name as Samuel Billings and said he was with the anti-fraud unit of the Department of Commerce Federal Credit Union. In the complaint she would later file with the FBI, Sharples said she hadn’t realized the call had somehow been rerouted.

Sharples said trying to reach the phone number on her card — which she thought was the safe course of action — helped to convince her she was dealing with her credit union. It’s unclear how such a call would be intercepted, although her phone provider later told her a forwarding number she did not recognize had been added to her account.

Commerce Federal chief executive Patrick Collins declined to comment on customer matters or credit union protocols but said fraudsters are becoming more sophisticated.

Billings also raised alarms about the danger to her bank account. He repeated the amounts, down to the penny, of the three attempted withdrawals she had been warned about. Sharples was terrified she could lose it all.

“The whole premise of this was: You need our help to protect your money,” she said.

Billings told her he would help her move it somewhere safe. Working in silent partnership, Billings and his fake Microsoft accomplice got to work on the next stage of their business plan: methodically cleaning out Sharples.

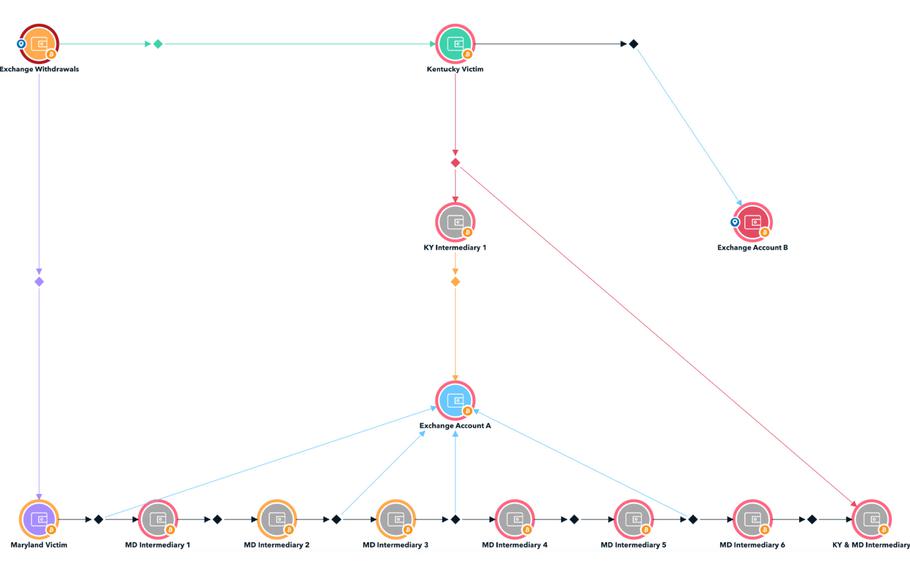

This analysis by TRM Labs for The Post traces the flow of more than $600,000 worth of bitcoin from a Binance.US account set up in Sharples’s name (orange dot). The stolen funds flow from the exchange to an address labeled Maryland Victim (purple dot), then to various intermediaries in an effort to obscure their movement. The analysis also shows more than $300,000 in cryptocurrency moving from an account set up in the name of a retired couple in Kentucky (green dot). They were victimized using similar tactics and the same phone number that was used to call Sharples. Some of those funds from both sets of victims end up in the same account (blue dot). The FBI seized funds in the Kentucky case from an account that was connected to the overall criminal network (red dot). (TRM Labs)

Washington and the White House

As a New Yorker, Sharples didn’t have much need for a car.

That changed in her 20s, when she started commuting on dirt roads to a field station in California’s High Sierra mountains to trap and map the habitats of four species of chipmunks for her ecology dissertation. She bought a beat-up 1967 Chevy station wagon with a rusted-out hole on the driver’s side floor for $375.

Sharples drove 2,500 miles from the University of California at Davis to East Tennessee in 1978 to launch a career as an environmental scientist at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, established as part of the Manhattan Project. In the mid-1980s, she spent one year as a science fellow on Capitol Hill for Tennessee’s Albert Gore Jr., an experience that opened a curtain to Washington.

When Gore held a hearing on genetic engineering — at a time when scientists were sharply divided on the emerging capabilities — Sharples sat beside the congressman, passing notes and prompting him to probe further. “It was so cool,” she said.

One failed marital engagement in Tennessee and 11 years later, she engineered a permanent return to Washington, where she served as a senior analyst at the Office of Science and Technology Policy during the Clinton White House. She worked on tightening ozone and other air quality standards covering smoke and soot as industry interests butted against health advocates.

Sharples spent nearly 20 years as director of the Board on Life Sciences at the National Academy of Sciences, the private society of scholars established by Congress that provides scientific advice to the government. During the Bush administration, she helped to oversee ethical guidelines on stem cell research. After the Sept. 11 attacks, her focus at the academy moved to biosecurity.

Despite the stress, the White House was “the most fun I have ever had in a job,” she said.

Safe haven account is emptied

Samuel Billings, masquerading as a savior from her credit union, said he needed to create a protected investment account for her. He opened it in her name at cryptocurrency exchange Binance.US, the U.S.-based affiliate of cryptocurrency giant Binance.

“Happy trading!” read the confirmation message.

Billings started small, saying Sharples first needed to protect the $25,000 in her savings account at Commerce Federal. Williams would keep her on the line from 7 a.m. until bedtime — claiming to be removing malicious software from her computer but mostly lingering silently — for more than two weeks.

Finally, a document appeared on her screen with a list of account names and numbers. Print it out, Billings told her. Drive to your credit union.

She did.

According to the script he gave her, if asked, she should say she was moving the money to her investment account, something she does frequently.

She handed over the sheet directing the $25,000 be transferred to the Binance.US account on Feb. 25, 2022. Documents from Binance.US and her credit union show the money was moved via a Las Vegas-based financial firm known as Prime Trust LLC, which provided technology services to Binance.US, and Signature Bank.

(Earlier this year, Nevada regulators moved to shutter Prime Trust, citing “unsafe” financials, and it filed for bankruptcy. Signature Bank failed because of poor management, according to federal regulators, and its assets were taken over by another bank. Current and former executives from the companies did not respond to requests for comment.)

Billings guided Sharples around the new account on her screen, showing her the money had arrived. He gave her a password to put her at ease: Blacklist@123.

At 9:26 a.m. on March 1, Binance.US’s automated system emailed Sharples three times, saying she had purchased bitcoin, twice for $10,000 and once for $5,000. The digital money was parked in her new account.

Two minutes later, Binance.US emailed Sharples again to confirm she had asked to transfer the newly purchased bitcoin back out of her account.

“This link will expire after 30 minutes for security reasons,” it read.

What Sharples didn’t know was Billings and his associates, who could reach into her computer remotely, prevented her from seeing most emails from Binance.US. Within 26 minutes, the account that was supposed to be her safe haven was empty and the scammers were preparing their next move.

Growing cases of financial ruin

Criminals behind the global explosion in cyberscams are psychologically sophisticated, experts say. They’re patient. And their victims are seemingly everywhere, left wrestling with financial ruin and humiliation.

A divorced and lonely home builder from Sharples’ Maryland suburb had $178,000 in retirement savings stolen last year. A seemingly random text message led to a prolonged bout of text flirting, and eventually a trading scam using an intricately designed website that showed soaring, but phony, returns.

Starting in 2020, a 79-year-old woman who played Words With Friends Classic on restless nights after aiding her husband through another day of dementia was being scammed out of $390,000. They also got her engagement ring. The criminals found her through the app, offering companionship and a sense of purpose into this year by conjuring an elaborate tale of an American trapped overseas.

“The manipulation is cruel,” said Montgomery County, Md., police Detective Michael Adami, who investigates such scams.

Scammers have built up a criminal ecosystem and follow market-tested formulas.

An India-based researcher, Siddhesh Chandrayan, unearthed a return-on-investment spreadsheet used by tech support scammers to sharpen their game. The criminals have help desks, software to manage call volumes and specialists who generate leads, according to Amy Hogan-Burney, a former FBI attorney who is Microsoft’s general manager for cybersecurity policy and protection.

“There should be no shame in being the victim of this, because this is organized crime,” Hogan-Burney said.

U.S. law enforcement, from local police to federal agencies, is struggling to match the soaring growth in cyberscams and cybercrimes involving cryptocurrency, which allows funds to rocket overseas. The FBI estimates more than $10 billion was lost last year through cybercrimes involving romance, investment, government impersonation, tech support and other scams, up from $6.9 billion in 2021.

‘It’s my idea’

With Sharples’ regular savings account wiped out, the criminals eyed a bigger prize: her retirement account.

She had been setting aside money for decades, including in a tax-deferred account. Billings told her to cash it out and transfer the money to her credit union.

At that point, a precaution set up to backstop bad customer decisions kicked in. After Sharples asked TIAA — which managed the retirement account — to transfer her money, a senior fraud investigator with the company called to question her decision.

“Is someone else telling you to do this?” he asked.

“No, it’s my idea,” she said, following the script. “I’ve decided I want to invest in a different way.”

TIAA did what Sharples asked.

That had big tax consequences. As required, TIAA set aside withholdings to cover federal and state taxes. Then it transferred the remaining $630,000 to her credit union.

With those hurdles cleared, the script and procedure at her credit union would be the same as the first time she transferred money.

Sharples scratched out “$25,000” in the script, wrote in “$630,000” and headed for the Commerce Federal to make a transfer that would change her life. The money, as before, flowed into the Binance.US account in her name.

It was gone within two hours.

But it took days before her relief at moving the money to safety gave way to growing unease.

She was concerned she still didn’t have access to the funds, and Billings, who had seemed to treat her with kindness, was pushing hard for her to withdraw her final asset. Sharples had a separate retirement account with about $1 million, but it had tighter limits on what could be taken out because the funds were contributed by her employer.

Billings insisted she close that account and move the money to her credit union. Sharples balked. She called back the fraud investigator at TIAA and told him what was happening. He said it sounded like she’d been taken. In a statement, TIAA said it seeks to aggressively counter such “despicable attempts by unscrupulous scammers.”

Sharples called the man supposedly from Microsoft, telling him she had lost confidence in Billings and didn’t want to take out her money. She was transferred to a supervisor and got an expletive-filled rant.

“It was like telling me, ‘Well, you’re a fool!’ ” Sharples said. “ ’We’re trying to help you!’ ”

Within minutes the phone numbers were dead.

2017 tax law removed deduction

Sharples didn’t know the U.S. government would profit from the crime.

“I figured, ‘Well, there’s got to be some way that someone who’s been victimized, as I have, gets a pass, right?’ ” Sharples said.

The U.S. tax code has long drawn a clear line: When someone takes money from a tax-deferred account, the IRS considers it a distribution. And distributions generally get taxed, regardless of what happens with the money.

That meant Sharples, who had a comfortable income in semi-retirement, suddenly looked like a millionaire to the IRS.

As she prepared her taxes online, Sharples was sickened by what she saw on her Form 1040, which showed the fraud raising her taxes by hundreds of thousands of dollars. She was then drawn through an excruciating education in the nation’s sprawling tax code.

Before 2018, Sharples would have found a long-established deduction for individual theft victims. But congressional Republicans changed the provision in 2017 as part of the biggest overhaul of the tax code in decades. To offset some of the cuts, its drafters suspended the provision through 2025. This year, more than 100 House Republicans co-sponsored legislation that would make the change permanent.

The House’s tax-writing committee said in 2017 the repeal of a deduction that helped theft victims was part of an effort to make the tax system “simpler and fairer for all families and individuals.”

Told of the potential consequences of the law change for Sharples and others, an aide to a senior GOP member of the Ways and Means Committee — who agreed to describe the committee’s reasoning on the condition of anonymity — said “tax provisions like this were removed to offset the cost of lowering tax rates for everyone.”

The Biden administration has defended the Trump-era tax law in court, arguing Congress acted deliberately when it suspended tax relief for individual theft victims. The Treasury Department would not comment on Sharples’ case or, more generally, on victims in similar circumstances identified through interviews and court records. A Treasury spokesperson declined to say whether the administration wants the law changed.

The IRS wouldn’t comment on Sharples’ case and said in a statement it enforces tax laws written by Congress.

An IRS customer service representative was sympathetic to Sharples and said her predicament was horrible, she recalled.

“He was very nice. It didn’t help a bit,” she said, adding that he told her the government could help establish a payment plan for the full amount.

Anguished, losing weight and considering remortgaging her home to cover the taxes, Sharples appealed to former colleagues and others for help. An accountant pointed to a special IRS procedure established in 2009 to aid victims of Bernie Madoff and those caught in similar schemes.

She filed her taxes using the procedures, which allow victims of Ponzi-type investment schemes to deduct investment losses if they meet certain criteria. The procedures have seen a revival since passage of the 2017 tax law and as cyber and cryptocurrency frauds have mushroomed.

The number of taxpayers claiming deductions through the Madoff-era process has shot up, IRS data shows. By 2020, taxpayers were seeking about $700 million in such deductions, up from $85 million in 2017. The IRS and the House GOP aide both noted the Ponzi-related provisions, among others, could help some victims.

“If there are unintended consequences from legislation passed into law, outside of flexibilities granted to the Secretary [of the Treasury,] the IRS does not have the authority to resolve them,” the IRS statement said.

Sharples ended up paying more than $100,000 in federal taxes on the amount stolen.

‘I wasn’t thinking clearly’

For Sharples, losing $655,000 to the scammers, plus the taxes on what they took, means replaying in her mind the red flags she missed. The guy keeping her on the phone day and night? A form of coercion. That password to her crypto account? Blacklist@123. Come on.

And perhaps the biggest short circuit in her analysis: If her purported helpers from Microsoft and Commerce Federal were so adamant her bank account was at risk, why would they tell her to rush more than $600,000 into that account?

“I wasn’t thinking clearly,” she said.

She is clear-eyed now.

A researcher who has surveyed scam victims said the focus on frightening Sharples is a tactic informed by science. The scammers were disabling her defenses from within.

“We know fear arousal is a pretty powerful motivator,” said Marti DeLiema, an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota School of Social Work. “We also know that in states of high emotional arousal, whether it be a negative state like fear or a really positive state like excitement or anticipation of some positive reward, information bypasses that critical, rational, deep-thinking part of the brain.”

When Sharples told her partner, Alan Gerstle, what happened, he said he couldn’t believe criminals would do such a thing to a good person. The writer and tutor only vaguely knew she had computer problems.

Gerstle and Sharples have known each other since they were teenagers in New York, but still broach the theft gingerly. Sitting in a bright dining room decorated with ceramic bunnies, Gerstle said along with her money, Sharples also lost her faith in people.

She is competent and sympathetic, a scientist who loves literature and is a good judge of character, Gerstle said. But they started with different worldviews. He assumes the more helpful someone appears, the more skeptical he should be. She was trusting.

“I wouldn’t say something like, ‘Well, I’m glad that you’ve learned your lesson,’ ” Gerstle said.

“If you did, I would have punched you in the nose,” she said.

Scammers’ misstep shows multiple victims

Around the time Sharples was targeted, some in that same criminal network appeared to hit multiple victims, according to an analysis performed for The Washington Post by blockchain analytics firm TRM Labs, which helps federal investigators. The scammers left a cryptocurrency wallet address in the recycling bin on Sharples’ computer desktop, providing clues.

Using that information and TRM’s software, Chris Janczewski, the firm’s head of global investigations and a former IRS Criminal Investigations special agent, followed Sharples’ money, which the criminals had converted to crypto and sliced and diced into numerous wallets “to make it harder for people to trace and to obfuscate the illegal source,” he said.

Some of Sharples’ stolen savings were funneled to an account that received proceeds from other scams, including one in Kentucky, Janczewski said. Whether the account was controlled by the scammers or their money launderers, it saw $5.6 million in transactions over a few months, he said, hinting at the scale of one small slice of the scam economy.

The Kentucky victims were an elderly couple who sent more than $370,000 to tech support scammers who used similar tactics and the same telephone number given to Sharples, according to interviews and an FBI affidavit.

The FBI seized about $340,000 in cryptocurrency from four people in the Kentucky case — two linked to China, two to India. The currency had been hosted at Binance, which handed it to the FBI. But that law enforcement breakthrough could bypass Sharples. Janczewski said the seized cryptocurrency originated from an account that did not appear to include Sharples’ funds. Because of that, Adami said, it wasn’t clear if Sharples would be entitled to any of it. An FBI official in Kentucky declined to comment on the forfeited assets.

Records from Adami’s investigation indicate an account that received Sharples’ funds was accessed in the United Arab Emirates, he said. The account holder’s identity has not been confirmed, and it’s unclear whether they knowingly participated in the theft.

After The Post approached Microsoft with details of Sharples’ case, the company’s digital crimes unit launched its own investigation. Efforts to thwart pretenders abusing the company’s name stretch back to 2014. They believe, based on preliminary findings, that her case is linked to a broader operation in India. Company investigators are developing a criminal referral with evidence for law enforcement.

Sharples was interviewed by an FBI agent last year and was notified an investigation was underway. The agent’s questions centered on Binance, she said. In November, Binance and its founder, Changpeng Zhao, pleaded guilty to violating anti-money-laundering requirements and other offenses, agreeing to pay more than $4 billion to resolve a multiyear Justice Department investigation. Binance said it took responsibility for past shortcomings to “lay the foundation for the next 50 years.”

The criminals who hit Sharples used her money to make dozens of bitcoin purchases within minutes, each valued at $9,950. The cryptocurrency was then quickly transferred elsewhere, a sequence that experts said suggested money laundering or other criminal behavior.

Binance.US said in a statement that it prioritizes user safety and requires multiple levels of verification. But, it added, if a wallet address has no signs of nefarious activity ahead of time, transactions with it can’t be systematically blocked.

Sharples saved for nearly four decades. Within weeks, almost half of it was gone, she said, making a pistol gesture with her forefinger. “It’s like being shot in the head.”

‘I already paid a terrible price’

Starting from the moment the big warning sign froze on her computer screen, Sharples was being hunted.

“They had overwhelmed me,” she said, sitting at the keyboard in her study, surrounded by the scientific reports and photographs of a life marked by public service and adventure.

On the far wall is a framed photograph she took on safari, the kind of overseas journey she once hoped to do more of in retirement. It shows a pack of perky-eared jackals burrowing into their striped prey.

“I’m the zebra,” Sharples said.

In the 21 months since she was defrauded, Sharples has cycled between phases of suffering. Sometimes she’s, in her word, morose, accepting but unhappy. Other times she is depressed or obsessed.

She’s had to force herself not to think about it constantly, finding joy with her shepherd-terrier rescue Timothy at the dog park, devouring mystery novels set in Egypt or connecting with her yoga teacher, who hails from Mumbai.

But the darkness sometimes hits. One late-summer night, she was recalling the mantras from the people who have tried to help her.

You are a victim.

These people are really good at what they do.

It’s not your fault.

It’s not because you were stupid.

“Everyone has said, ‘You shouldn’t feel that way.’ At the end of the day, I do. I feel that way,” said Sharples, burrowed in bed, her voice cracking. “I’m never going to stop feeling like it was my fault, because I made a stupid mistake, and I already paid a terrible price.”

She was worried about her finances and fixated, again, on the day she lied to the fraud investigator before she sent her money to strangers: Are you sure? Is someone else telling you to do this?

If there had to be one worst decision, maybe that is the one, she said.

“I have a f---ing Ph.D. I’m not a stupid person,” she said, crying, her dog at her side. “I should have known better.”