U.S.

Dreams dying in a Texas city where immigrants fought for an education

The Washington Post November 21, 2023

Sisters Daniela, 19, and Joseline Leyva, 18, wait to take part in Tyler High School’s senior night at Christus Trinity Mother Frances Rose Stadium in Tyler, Tex., on Nov. 3, 2023. (Desiree Rios/for The Washington Post)

TYLER, Texas — Joseline Leyva knotted her long black hair and pulled on her gray beret, topping off her dress blue Army ROTC uniform. It was senior night, the last high school football game of the season and the 18-year-old soon would be honored on the field.

“I am the future of the United States of America,” Leyva recited, recalling the Junior ROTC cadet creed she has spoken every week for the last four years.

But that’s not how the law sees Leyva. Brought to this country by her parents when she was a 1-year-old, Levya is an undocumented immigrant.

For hundreds of thousands of people who came to the United States as children without immigration papers, their only stability has come from DACA — Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals.

That program, created in 2012 by President Barack Obama, offered protection from deportation and access to a driver’s license and a work permit. It was supposed to be a temporary measure while U.S. lawmakers decided on a permanent policy. Polls consistently show that about three-quarters or more of Americans support allowing the young people — often known as “Dreamers” — to stay in the United States.

Congress, however, has been paralyzed on the issue. And now DACA is in jeopardy, pushed to the brink by Republicans who say Obama overstepped his authority. Then-president Donald Trump called the program an “illegal” amnesty and tried to phase it out in 2017. Court orders stopped him.

But a lawsuit led by the state of Texas arguing that Obama didn’t have the power to create DACA without Congress could reach the conservative-dominated Supreme Court. A decision in favor of the plaintiffs could spell the program’s end.

As the appeals churn on, DACA has been limited in recent years to existing applicants. Leyva is part of a new generation of high school students locked out of the program. Advocates say the number of high school graduate Dreamers without DACA will soon surpass the nearly 580,000 immigrants who have it.

The disconnect between public opinion and public policy on Dreamers reflects how the work of government often stalls due to American democracy’s distortions.

Latinos — who make up the majority of Dreamers — are substantially underrepresented in the Senate, where legislation to establish a path to citizenship has been blocked by filibusters. The existence of DACA was threatened by a president, Trump, who won the electoral college but lost the popular vote. It could still face elimination by a Supreme Court in which four of the six justices comprising the conservative majority were confirmed by senators representing a minority of Americans.

The result has been that undocumented people who arrived in the United States as children and want to remain are either stuck working illegally or living in fear that the thin legal protections they have can be taken away. Because so many are now shut out of DACA, hundreds of thousands of them cannot pursue careers in the United States, exacerbating shortages of doctors, nurses, first responders, teachers and other in-demand positions.

That dynamic is particularly poignant in Tyler, a city about two hours east of Dallas that made national headlines in the 1970s for trying to keep children out of public schools because they did not have legal permission to be in the country.

The U.S. Supreme Court rejected the policy in a landmark 1982 ruling that said all children deserved a basic education, regardless of their immigration status.

Obama announced DACA on the 30th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision, symbolically cementing this city’s place in the history of U.S. immigration law. But the court didn’t say — and has never said — what should happen to these children after they graduate from high school with dreams of college and careers, or even service in the U.S. military.

Levya is prohibited from enlisting as a soldier despite her years of preparation because she is not a legal U.S. resident. As she got ready for senior night this month, her parents added nervous last-minute touches. Her dad dabbed her high-polish black shoes with a tissue. Her mom pulled a stray hair from her sleeve.

“It is sad when I see other people that have what I want to have,” Levya said, standing in her dining room with her many JROTC awards laid out on the table. “It’s hard because I would want to go to the military and fight for them, even though they don’t accept me.”

Joseline Leyva, a high school senior and member of the JROTC program at Tyler High School, adjusts her beret at her home before attending her school’s football game. (Desiree Rios/for The Washington Post)

A hidden history

Tyler was a booming oil and railroad town in the 1970s when it became the test case for America’s treatment of undocumented schoolchildren, most of them from Mexico.

School officials had noted an uptick in their numbers in Tyler, even though it was hundreds of miles from the southern border. The officials voted in 1977 to charge $1,000 a year in tuition for each undocumented child, citing a new state law that authorized the practice and that passed the legislature without a single hearing. Children whose parents couldn’t pay had to leave school.

The community then was mostly White and had already resisted racial integration in schools, defiantly opening an all-White high school for Confederate General Robert E. Lee in 1958 after the Supreme Court struck down school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education.

Civil rights lawyers argued the tuition rules were unconstitutional and discriminated against poor children. Up to 60 of the district’s 16,000 students were undocumented, and only four families were willing to risk deportation to sue.

The Lopez family, Mexican immigrants who had agreed to become a plaintiff in the case, had three children in a local elementary school. They squeezed their belongings into their Dodge Monaco and drove two blocks to the courthouse for the first hearing. They wanted to be ready in case immigration agents were waiting.

“We were afraid. They could have taken us away,” said Lidia Lopez, now 76 and still living in Tyler.

Judge William Wayne Justice, a liberal in conservative East Texas, took the extraordinary step of scheduling the hearing before dawn and gave each of the plaintiff families a pseudonym to protect them from public backlash.

Justice ordered the children back to school so fast that they barely missed any classes.

Stripping children of a basic education would condemn them to a life of low-wage work, he later wrote, especially when all sides agreed that Congress was likely to pass a law giving them a path to citizenship.

The school system fought the case — known as Plyler v. Doe, for schools superintendent James Plyler — all the way to the Supreme Court, which struck down the state law in 1982.

“It is difficult to understand precisely what the State hopes to achieve by promoting the creation and perpetuation of a subclass of illiterates within our boundaries,” Justice William J. Brennan Jr., a liberal, wrote.

With that decision, public education for all, regardless of immigration status, became the law of the land. As Justice had predicted, Congress passed and President Ronald Reagan signed a law in 1986 that put the Lopez children and nearly 3 million others on a path to U.S. citizenship.

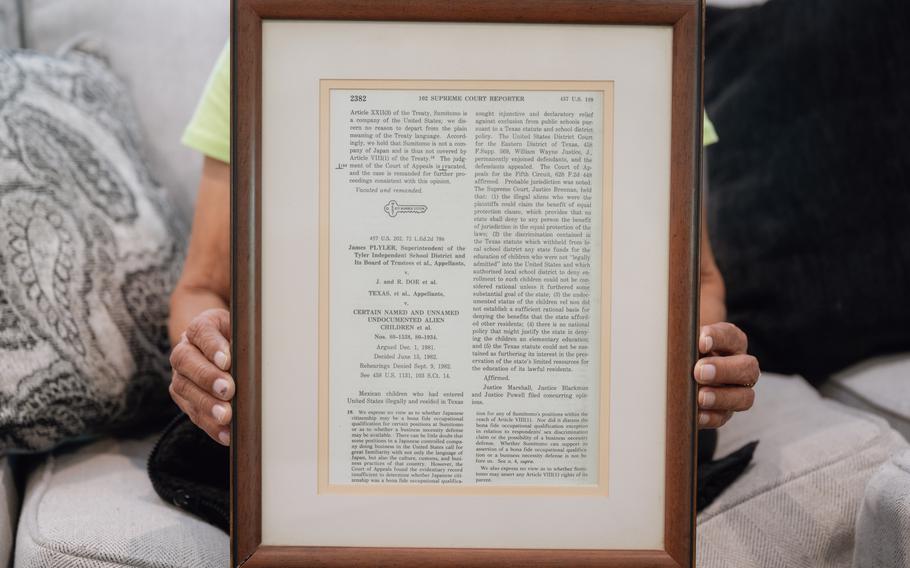

Most of the Lopez children graduated high school and still live and work in Tyler, where a framed copy of the court’s decision hangs on their parents’ wall.

The discrimination that the Lopezes faced stings all these years later. In their family now there are registered nurses, police officers, a legal assistant and an accountant in training. They don’t have to imagine life without a future in America.

Israel Aguirre, 17, and Joseline Leyva get snow cones during the football game. (Desiree Rios/for The Washington Post)

Graduating into nothing

Joseline Leyva and her older sister, Daniela, were toddlers when they arrived in Tyler with their parents from Mexico in 2006. Their father quickly found work as a landscaper and their mother as a cook.

In a city with plenty of Mexican restaurants, landscaping and construction businesses owned by undocumented immigrants, they bought a house and built a life for their young family.

After Reagan’s amnesty, illegal immigration to the United States soared. Hundreds of thousands of new undocumented children passed through America’s public schools. In Tyler, White residents now account for less than half of the population and in Tyler public schools, Latinos are about half the students.

Joseline Leyva said she has loved growing up in the friendly city known for its rose gardens, state fairs and elegant brick streets. She marched in the Christmas parade, carried the American flag in the color guard at football games and served free meals to retired military service members for Veterans Day at the Golden Corral restaurant.

But life has felt more precarious since 2017, when the Trump administration tried to terminate DACA just as the Leyva sisters were approaching 15, the minimum age to apply.

Amid the legal wrangling, a judge ruled that the program must stop taking new applications. The Leyva sisters were shut out, even though many of their slightly older friends had DACA and its protections.

They were left facing the dilemma that had prevailed before DACA: Safe until graduation, but little chance of putting a diploma to work after that.

Daniela Leyva, now 19, had high hopes of a professional career. She had earned good grades and won admission into Tyler’s competitive “early college” high school program, where she received her high school diploma and an associate’s degree at the same time.

She graduated in 2022 and won a partial scholarship to the University of Texas at Tyler. But undocumented children are ineligible for federal aid, so she chose the quickest path to a job instead. She tried to become a medical assistant, then a real estate agent. But without DACA and a Social Security number, she couldn’t get her license in either field.

Now she works a cash-only job as a barista. She dreams of becoming a registered nurse, but that’s impossible until the laws change.

“My parents, they came here at my age, with two little girls, with a dream. So I’m not going to give up,” Daniela said, her voice shaky as she sat on the couch in her family’s living room decorated with framed family photos.

At night her mother, who did not want to be named for fear of being discovered and deported, lies awake wondering how she could help. They had left Mexico to live in a place with less crime and violence and to build a better life. They had celebrated Daniela’s graduation and took pride in all her academic awards and accomplishments.

Now she gently warns her daughters that they are in the same predicament as their parents, at risk of being exploited at work or deported. The Biden administration has prioritized deporting criminals and recent border crossers, not long-term residents. But in a new administration, the family and others like them could become targets for removal.

“Look at Daniela - she had her moment and now it’s at a standstill. Dreams are getting frustrated. They’re stopping,” said her mother, 39.

Joseline Leyva found her calling in the Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. She said the program taught her strength, persistence and discipline. She lost 50 pounds from rigorous physical training. The Army named her Tyler High School’s top cadet in 2021 and praised her “outstanding mental and physical endurance.” She dreamed of enlisting right after high school.

But that path is blocked. She sees the congressional inaction and the court challenges to DACA. She has watched with trepidation as her neighbors in conservative Smith County, which includes Tyler, overwhelmingly voted for Trump and other GOP officials who want to eliminate DACA, tighten security at the borders and deport as many undocumented residents as possible.

For years she has set those worries aside, still in high school, still supported by teachers and friends. Even the Army encouraged her to stay in touch in case Congress passed a law allowing her to become a permanent legal resident. But there is no sign of that happening soon.

David Stein, chairman of the Republican Party in Smith County, said he understood that many undocumented people were facing a “gut-wrenching situation” over the uncertainty of DACA’s future.

But he said GOP officials were alarmed at the situation on the southern border under President Biden and that GOP lawmakers should not act on DACA-related legislation until the border is closed to all illegal immigration.

“We have to secure the border - this is totally out of control,” Stein said. “That is what’s stopping the Republicans from engaging.”

Congress has come close on multiple occasions to passing legislation that would have granted Dreamers a path to U.S. citizenship. In 2010, for instance, the House passed a bill and Obama was prepared to sign it. In the Senate, where Latino voters are underrepresented because of their concentration in populous states that have the same number of senators as every other state, a majority supported the measure. But that wasn’t enough: Even with 55 votes from senators representing 60 percent of the country, the measure went down to defeat, done in by the filibuster.

Protections for Dreamers — of which there are believed to be about 2 to 3 million in total — have been filibustered multiple times since 2001. Attempts at a bipartisan compromise — in which border security is tightened and some undocumented immigrants are given a path to citizenship — have similarly come up short.

Opposition to protections for Dreamers has come predominantly from Republicans, who say they want to prioritize stopping the waves of new arrivals from crossing the border. Record numbers of migrants have been taken into custody since Biden took office, including historic flows of children and teenagers, overwhelming U.S. cities and towns that were unprepared to absorb them.

The border arrivals have frustrated Sen. Lindsey O. Graham (R-S.C.), co-sponsor of the Dream Act with Sen. Richard J. Durbin (D-Ill.). In September, Graham interrupted a Senate hearing about book bans to urge Democrats to take a more serious approach to enforcement. Only then could a legalization program pass, he said.

“The problem is so much bigger than it was before,” Graham said at the hearing, which Durbin chaired. “America is under siege and we need to fix this problem.”

Still, political pressure on the Dreamers question is growing as Latinos, now 19 percent of the U.S. population, grow in numbers and political clout. With the labor market tight, elements of the business community have pushed for a change, hoping to unlock an underutilized workforce.

Scott Martinez, president of the Tyler Economic Development Council, said immigrants, including the undocumented, are already “very integrated and very productive members of our community.”

He said they work in health care, manufacturing and other key Tyler sectors — some of which require any would-be job applicant to have DACA, at a minimum.

But at least for now, the flow of young people securing DACA protections has been halted. Approximately 100,000 first-time applicants nationwide have each paid $495 application fees - nearly $50 million - that cannot be processed under court orders. Tens of thousands of others cannot apply because they arrived in the United States after 2007, the cutoff when Obama created the program.

Paulina Pedroza, a community advocate, said the situation is especially desperate because the generation of students graduating from high school today was raised to believe that DACA would be available to them.

“It was a promise,” she said. But without work permits, she said, “there’s no hope for them.”

Lidia Lopez holds a framed copy of the Supreme Court decision, given to her by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which represented them in court and is fighting for DACA today. (Desiree Rios/for The Washington Post)

Living with constant fear

Even those who have DACA face the possibility of having their lives upended.

The Texas lawsuit is widely expected to reach the Supreme Court within the next couple of years. And the conservative-dominated court — with 6 of 9 justices appointed by Republicans, despite Democrats winning the popular vote in 7 of the past 9 presidential elections — could strike it down.

The Biden administration has been trying to save the program, saying it has transformed the lives of more than 800,000 people who have cycled through the program over the last decade.

Some have realized their aspirations of becoming doctors, nurses and lawyers. Others enrolled in the military via a now-suspended program that put them on a fast-track to legal residency and U.S. citizenship. Many are simply working slightly better jobs than their parents and gaining a foothold in the middle class.

Sitting in the Cup O’ Joy Teahouse, a small business that Blanca Villanueva opened in Tyler in 2019, the 30-year-old said she has learned to manage uncertainty.

Born in Tijuana, Mexico, her parents brought her to Tyler on a tourist visa when she was 10. She graduated with honors from high school in Tyler in 2011, the first in her family to earn a diploma.

Villanueva had no hope of working legally. She thought about nursing, law or teaching, but she knew it would be impossible to become licensed without legal status. That changed with the creation of DACA.

She earned an associate’s degree in education at Tyler Junior College, then faced a choice: two more years to a bachelor’s degree and a career in teaching, or open her own small business.

She knows that if she used her DACA status to get a state teaching license, that career could disappear overnight if the program were struck down by the courts. But even if DACA were eliminated, she could still run her small business.

“We’re not very stable with DACA,” she said, adding, “But we’ll have an income with this place.”

So now she runs the shop, which is decorated in bright pinks and purples and sells big cups of boba tea and sweets, with help from her mother. Her toddler daughter, Bianca, watches videos as customers order teas, floats and frappés.

She said she owns her own house and pays property tax, along with income tax, business tax and sales tax. And every two years, she pays nearly $500 to renew her DACA status and work permit.

“They’re not in our shoes,” she said of critics. “They think that we’re taking everything. They don’t know what we’re doing. Because I’m working for my money.”

Joseline Leyva, right, watches the newest color guard cadets present the flags before the football game. (Desiree Rios/for The Washington Post)

An American tradition

It was Friday night in Tyler. The lights were blazing at Rose Stadium and the home stands were filling up on a cool evening for the final football game of the season, between the Tyler Lions and the Forney High School Jackrabbits.

Music pounded from the huge video scoreboard as the cheerleading squad strutted in their white cowboy hats and sparkly uniforms. Amid the joyful atmosphere, Leyva waited with her parents and sister for the senior night program to begin.

Corey Cato, a retired U.S. Army sergeant who taught Leyva in JROTC, looked on and said he thought it was unfair that Leyva is now barred from enlisting.

“She’s great for the program,” he said. “She’s a good role model. She cares. She’s committed. She’s everything I would want to have for young soldier.”

Cato, who served 22 years in the Army, called it a “huge loss” for the United States that immigration laws were standing in Leyva’s way.

“If she hasn’t earned an opportunity yet to serve, who has?” he said.

Just before the game, dozens of seniors and their families walked onto the field: football players, cheerleaders, band members and JROTC cadets, all in their uniforms.

Leyva stood with her parents and her sister. The public address announcer introduced each senior and their family. When she called Leyva’s name, the family walked forward, smiling.

They marched proudly and publicly under Texas’s famed Friday night lights, four undocumented immigrants being warmly embraced by Tyler and celebrated as part of an American tradition.

When they reached the sideline, they stepped off the field and melted back into the crowd.

Clara Ence Morse contributed to this report.