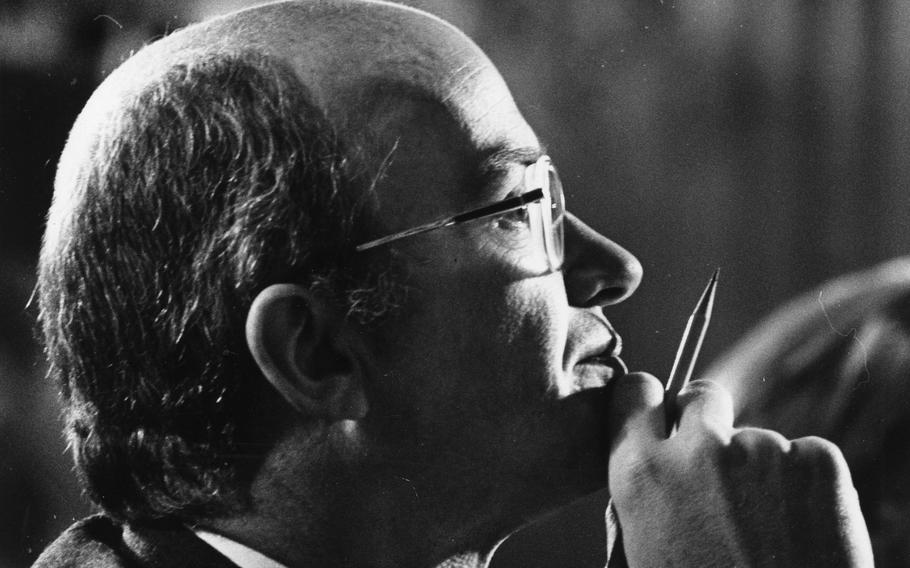

James Watt is pictured in this undated photo in Washington. (James K.W. Atherton/The Washington Post)

James G. Watt, who battled environmentalists during a rancorous term as interior secretary under President Ronald Reagan and offended even some allies with the uninhibited rhetoric that ultimately drove him to resign, died May 27 in Arizona. He was 85.

His family announced his death in a statement but did not cite the cause or specific location where he died.

At 42, Watt was one of the youngest members of Reagan’s Cabinet when he took office in 1981. Like the newly elected president, Watt was a Westerner — he came from Wyoming, the son of a Republican county chairman; Reagan had been a Republican governor of California — and he wore boots, although not of the cowboy variety, along with his thick glasses.

Upon his arrival as secretary, Watt telegraphed his agenda with an order that the American buffalo on the Interior Department’s official seal, which since the department’s founding in 1849 had faced to the left, be turned to look right.

During two years and nine months in office, he was a champion of private business, including oil, coal and other industries seeking what he deemed the necessary development of public lands, and a scourge of environmentalists, who regarded his nomination as a catastrophe for their cause.

William Turnage, the director of the Wilderness Society, declared Watt the “worst thing that ever happened to America.” Another environmental activist remarked that making him interior secretary — the steward of hundreds of millions of acres of federal land and the country’s national parks — was “like hiring a fox to guard the chickens.”

Watt, for his part, accused environmentalists of having “poisoned the press” against him even before he took office.

Their conflict with Watt, and his with them, was one of long standing. After serving in the Interior Department during the Nixon and Ford administrations, Watt helped found the Mountain States Legal Foundation, a nonprofit law firm where he served as president and chief legal officer. The foundation, based in Colorado, was funded by business executives including Joseph Coors Sr., a scion of the Coors brewing family and an influential backer of conservative causes.

In Watt’s description, the organization was established “to fight in the courts those bureaucrats and no-growth advocates who challenge individual liberties and economic freedoms.” Among other efforts, he and his colleagues pushed to open public lands to energy exploration and sought to limit the authority of the Environmental Protection Agency.

Like Reagan, Watt aligned himself with the “Sagebrush rebellion,” a movement to return federal lands, mainly in the western United States, to state control. When he took office as interior secretary, he invited committed environmentalists on the staff to “seek opportunities elsewhere.”

He moved quickly to grant oil, gas and coal leases on public land, to increase offshore drilling, to stop the expansion of national parks and to reduce federal regulation of strip-mining.

“I want to change the course of America,” Watt told The Washington Post in 1983. “I believe we are battling for the form of government under which we and future generations will live.”

“The battle’s not over the environment. If it was, they would be with us,” he added, referring to environmentalists. “They want to control social behavior and conduct.”

Watt thrilled parts of the political right with his unstinting pursuit of his mission, even as he upset some fellow Republicans, as well as his many critics on the left, with his inflammatory remarks. By his own admission, Watt went “from flap to flap.”

He declared that there are two categories of people in politics — liberals and Americans — in what he later said was merely “a good one-liner.”

To “see the failures of socialism, you need not go to Russia,” he observed. “Come to the American Indian reservations.”

Rebuking what he described as environmentalists’ effort to effect “centralized planning and control of the society,” he compared the conservation movement to Nazism and communism.

Watt drew widespread ridicule, and the disapproval of Vice President George H.W. Bush and first lady Nancy Reagan, when he moved to ban rock music from the 1983 Independence Day celebration on the National Mall in Washington, saying that rock bands attract the “wrong element” to what should be a wholesome family event.

He did not explicitly mention the Beach Boys, but they had performed at previous July 4 events, and the group became the focus of outrage over Watt’s pronouncement. President Reagan called the interior secretary to the Oval Office and presented him with a plaster foot bearing a bullet hole to humorously — but unambiguously — convey the message that he had shot himself in the foot.

“I’ve learned a lot about the Beach Boys in the last 12 hours,” Watt said, apparently chastened, “and we’ll look forward to having them here in Washington to entertain us again as soon as we can get it worked out.” (The Beach Boys ultimately performed in Atlantic City that year.)

Months later, Watt was speaking to a business group when he referred to a coal leasing commission as including “every kind of mix you can have,” remarking that “I have a Black, I have a woman, two Jews and a cripple.”

Watt apologized to the panel members and to the president for his “morally offensive” comment. The Post reported that “President Reagan stood by Watt to the end,” but amid burgeoning criticism from Republicans on Capitol Hill who saw Watt as an election liability, he resigned effective November 1983.

He was succeeded during the Reagan administration by William P. Clark and then Donald P. Hodel.

James Gaius Watt was born in Lusk, an oil and ranching town in eastern Wyoming, on Jan. 31, 1938. His father was a lawyer. Watt said his mother pushed him to gain a variety of experience in his youth, from work digging ditches to a job as a short-order cook.

Watt was a talented athlete, class valedictorian and prom king at his high school; he married his prom queen, Leilani Bomgardner, in 1957, when he was 19. They had two children, but a complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

Watt graduated in 1960 from the University of Wyoming’s College of Commerce and Industry and received a law degree from the university in 1962. In the early years of his career, he was a legislative assistant and counsel to U.S. Sen. Milward Simpson (R-Wyo.), the father of future U.S. Sen. Alan K. Simpson (R-Wyo.).

In 1964, Watt attended a meeting of a group called the Pro-Gospel Businessmen’s Fellowship, where business leaders spoke about the role of their religious faith in their work.

“The Holy Spirit moved on my life,” Watt told The Post. “I committed my life that very night.” He practiced a fundamentalist Christianity and during his time as interior secretary was quoted as saying that his “responsibility [was] to follow the Scriptures which call upon us to occupy the land until Jesus returns.”

In the late 1960s, Watt worked for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce on matters involving natural resources and environmental regulation. He later joined the Interior Department, where he served as deputy assistant secretary for water and power resources.

He was chief of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation before President Gerald Ford named him to the Federal Power Commission in 1975. Two years later, Watt helped start the Mountain States Legal Foundation.

After his tenure as interior secretary, Watt did consulting work, including for clients who sought and ultimately obtained funds from the Department of Housing and Urban Development for low-income housing projects in multiple states.

Watt’s work, in particular his reliance on contacts at HUD in the service of his clients, drew scrutiny in an independent counsel investigation into influence-peddling at the department during the Reagan administration.

Watt was charged in a 25-count felony indictment in 1995 with lying to Congress, a federal grand jury and the FBI in the course of the investigation. He ultimately pleaded guilty to a single misdemeanor charge of attempting to mislead a grand jury. He was fined $5,000, ordered to perform 500 hours of community service and placed on probation for five years.

The vast discrepancy between the original indictment and the one misdemeanor to which Watt pleaded guilty prompted The Post’s editorial board to describe the HUD investigation as an apparent “abuse of prosecutorial power.”

Watt was the author of the 1985 book “The Courage of a Conservative,” written with Doug Wead. The book, its title an echo of Barry Goldwater’s 1960 manifesto “The Conscience of a Conservative,” expounded on Watt’s vision of the movement to which he had devoted his career.

He was also the author of the book “Stuff That Matters” (2013), written for his grandchildren.

Reflecting on his work as interior secretary, Watt told The Post in 1983 that one must “pay a tremendous price” to change an entrenched bureaucracy.

“I’ve paid that price,” he said. “My objective was to bring basic change to resource management for America, to prepare us for the 21st century. I believe in the future.”

“Now, ideally, you would get the results, plus be personally popular,” he added. “Wouldn’t that be nice? Oh, I’d much rather be popular, and successful. But if I have to make the choice, I’ll choose success with results rather than success with personal glory.”