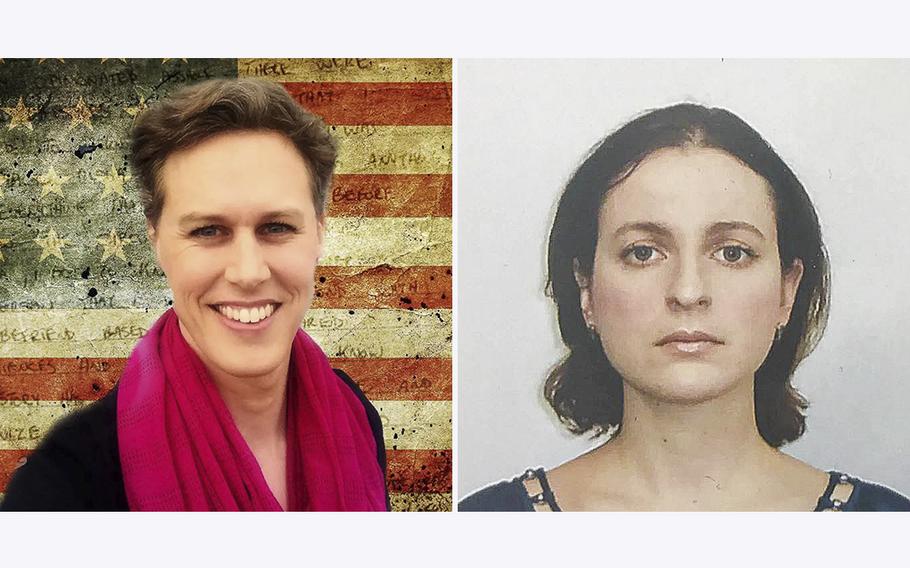

Army Maj. Jamie Lee Henry, left, who has been celebrated for being the first Army officer to come out openly as a transgender person, and Henry’s spouse Dr. Anna Gabrielian, an anesthesiologist at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Maryland. (Twitter, Linkedin)

BALTIMORE (Tribune News Service) — An email from a Johns Hopkins physician reached the Russian Embassy on March 1, 2022, five days after Russia invaded Ukraine, sparking a deadly war that has now spanned more than a year.

“My husband and I are both doctors. I’m an anesthesiologist, he works in intensive care,” Dr. Anna Gabrielian wrote in Russian, her first language, and referring to her spouse, Dr. Jamie Lee Henry. “We are ready to help if there is a need for that. We are for life, and do not want to cut Russia off from the international community.”

According to federal prosecutors, that email is evidence of the couple’s plot to assist an American adversary by abusing their positions as medical professionals. It spawned a monthslong investigation featuring an undercover FBI agent posing as a Russian government official. The agent met with Gabrielian and Henry, separately and together, recording their conversations covertly, eventually leading to an indictment charging the couple with conspiracy and disclosing identifiable health information.

But attorneys for the couple contend Gabrielian’s email underscores the doctors’ actual intent: to help preserve lives, regardless of nationality, at the beginning of a violent conflict. That matters, the defense lawyers say, because the government has to prove they communicated with someone they believed to be a Russian official for personal gain or with malicious intentions.

Gabrielian and Henry’s trial began in earnest Tuesday in the U.S. District Court in Baltimore, with prosecutors and defense attorneys previewing the evidence in the case. The attorneys on Monday selected a jury for the trial, which is scheduled for more than a week.

The government’s first witness, an undercover FBI agent who met with Gabrielian and Henry, began testifying Tuesday afternoon. She testified in “light disguise” and her undercover name, Lena Simon. For the duration of the agent’s testimony, the courtroom will be physically closed to everyone but attorneys in the case, court personnel and the jury. An audio feed of the agent’s testimony was broadcast into another courtroom for others to listen.

Aaron Zelinsky, deputy chief of the Maryland U.S. Attorney’s Office’s National Security and Cybercrime Section, said during opening arguments that prosecutors will play the approximately five hours of video of her meetings with Gabrielian and Henry, captured by the undercover agent’s discreet camera. They began playing the footage during the agent’s testimony.

The undercover agent first approached Gabrielian early the morning of Aug. 17, 2022, outside a garage at Johns Hopkins Hospital, catching the doctor by surprise.

“Anna. Anna Andreyevna,” the agent called out, referring to Gabrielian by her middle name, according to Russian tradition. Gabrielian, who was born in Russia and came to America with her family around age 10, spoke to the agent in Russian. Prosecutors worked with defense attorneys to produce an agreed-upon translated transcript of their conversations, and Gabrielian’s email to the embassy, which was in Russian. Footage played in court also featured English subtitles.

“How did you —” Gabrielian began to question the agent, as she did not include her middle name in her email to the embassy, or in a subsequent call.

“I was given your information, sort of,” the agent said.

The two agreed to meet again later, in the lobby of the agent’s hotel in Baltimore.

Small talk evolved into discussion about Gabrielian’s expertise and that of her spouse, Henry, an outgoing Army major at Fort Bragg, an installation in North Carolina and the home of U.S. Army Special Operations Command. Henry, who had secret-level security clearance, had previously treated wounded soldiers and veterans at Walter Reed National Military Center in Bethesda. The agent pressed Gabrielian about the help she and Henry could provide Russia.

“What I would like is to find out how I can be of most help,” Gabrielian said.

Gabrielian and Henry eventually met with the agent, using coded language to set up meetings and describe their discussions. They talked about the potential of accessing medical records of powerful politicians and military officials, according to prosecutors. In one of their meetings, Henry produced handwritten notes about his patients and a prescription list. The agent snapped photos.

“They had this information because they were doctors. And Dr. Henry wasn’t just any doctor, he was a military doctor,” Zelinsky told jurors, touting Gabrielian’s position at Johns Hopkins, where, he said, many “important” people get treatment.

Zelinsky described the couple’s efforts to avoid being identified, highlighting comments Gabrielian made about her fear of being caught, losing her career, family and freedom. He said the couple were recorded speaking about escaping to Russia if exposed.

“They sought to help Russia by providing the private medical information of their patients,” Zelinsky said, adding that the couple wanted to be “useful weapons.”

At the end of her first meeting with the agent, Gabrielian looked directly into the camera. She asked if she was being recorded, which the agent denied.

Defense attorney Christopher Mead said that’s when his client, Gabrielian, began to believe she was dealing with a Russian spy. As a Russian native, Gabrielian had reason to fear retribution for her or her family if she didn’t comply with the demands of the agent, Mead said, noting Russia’s authoritarian leaders past and present.

“What’re you going to do? Are you going to snitch a (Russian) agent out to the FBI?” Mead said.

Before trial, the government filed a motion to prevent the defense from claiming entrapment in opening statements. Without, using that word, Mead and David Walsh-Little, Henry’s attorney, suggested the FBI agent coerced the couple into providing any protected information in order to be able to charge them with crimes.

The undercover agent asked for confidential records 13 times before Gabrielian mentioned patient information, Mead told the jury. “These two doctors wanted to treat the sick, heal the wounded,” Mead said, describing the couple as “naive do-gooders” who fell victim to a “profoundly unfair undercover investigation.”

Walsh-Little said Henry, who is transgender, had no motive to help Russia other than to prevent the type of carnage of war Henry witnessed as a doctor at Walter Reed. The couple also contributed in the past to help Ukraine and other countries in advancing medicine, according to their attorneys. The prosecution’s case, Walsh-Little said, “makes no sense.”

In openings, Mead displayed images of messages Gabrielian sent to friends after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in which she expressed sympathy for the Ukrainian people.

“I feel awful saying this,” Gabrielian wrote, ”but I also feel bad for Russian soldiers who did not choose to be there.”

©2023 Baltimore Sun.

Visit baltimoresun.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.