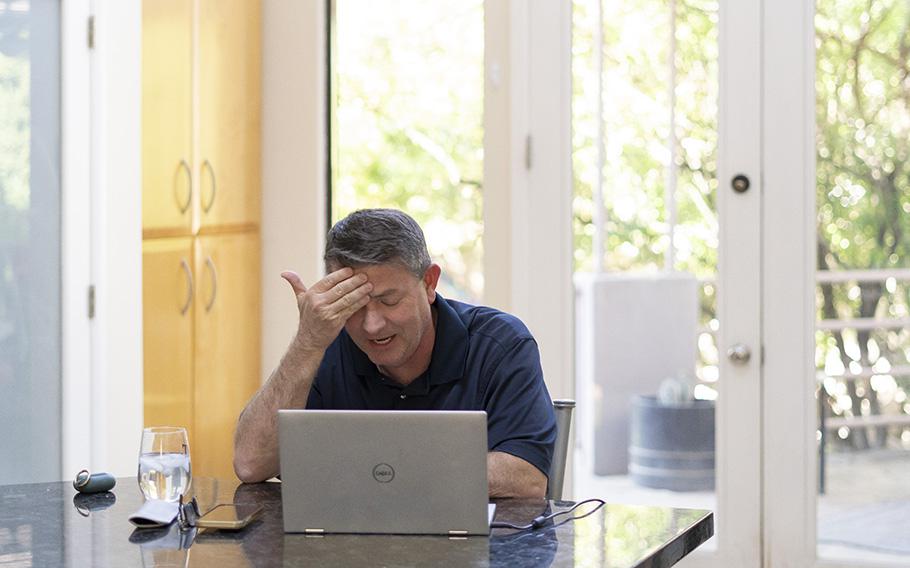

Bill Gates, a Republican elected to the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors, speaks to his therapist during a virtual session in his home in Phoenix. (Rebecca Noble for The Washington Post)

PHOENIX — Anger and resentment welled inside the local leader as he surveyed the mourners at his friend's funeral reception last year.

Bill Gates, 51, a lifelong Republican elected to the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors, stood with his wife and a friend and ticked off the names of those gathered around them who had betrayed him, their party and their country.

Gates stewed that they had done nothing as he and other leaders in Arizona's most populous county faced relentless criticism, violent threats and online harassment for upholding the results of the 2020 presidential election. They helped spread conspiracies about the voting process that turned him and his colleagues into targets. They stood by as his family lived in fear and briefly fled their home.

Because of their actions and inactions, Gates said, his integrity had been questioned. He was labeled a traitor who should be shot or hung. One person wrote on social media that his daughters should be raped. He worried that his own parents, avid Fox News viewers, might believe the lies about him.

At the reception, Gates began wildly waving his arms as he ranted. He was out of control and on the verge of disrupting the solemn gathering. His friend walked away. His wife, Pam, grabbed his arm tightly and shook him.

"What the hell are you doing?" she asked. "You've got to stop this. Stop it!"

The intensity of the past two years had delivered Bill Gates to the brink. His usual cheerfulness and folksy humor were gone, and he had grown sullen and lonely as he detached from those closest to him. He wasn't sleeping and had lost his appetite. He was always preparing for the next fight, and his ever-simmering anger would increasingly explode into view during public meetings, interviews with journalists and social gatherings.

A therapist would soon tell him he was experiencing classic signs of post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition typically associated with wartime veterans and violent assaults.

Gates is among many election officials whose lives were upended as they became high-profile targets under the notion that widespread fraud had tainted the 2020 election. It is an idea that continues to be promoted by former president Donald Trump and his allies.

Efforts to forcefully combat these narratives — including when Gates testified before the House Oversight Committee in October 2021 — are nearly always accompanied with threats and harassment.

Even today, more than two years after the election, it is not unusual for election workers to take different routes to their homes and offices to avoid being tailed, train in de-escalation techniques and bolster their home security systems. Conferences for election officials now double as group therapy sessions, opportunities to talk with their peers about the strain the work has had on their mental health and their families.

"This has been a family journey," Gates said, his voice cracking. "We're all working through this together. But we had to understand that we couldn't do this on our own. We had to reach out for help."

Before election denialism took hold, he had been an optimist — and in his mind, a model conservative.

He grew up watching C-SPAN after elementary school, founded a teenage Republican club and then pursued elected office. He preached low taxes and smaller government, first on the Phoenix city council and then as a county supervisor representing nearly a million constituents in one of the nation's most politically competitive areas. He led election integrity operations for the Republican Party and voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 general election. He served as a church catechist and had always taken pride in his integrity and decision-making.

By the spring of 2022, however, he had begun to question his own worth. He felt himself slipping away. His family did, too.

His wife said she no longer recognized the man she'd met on their college mock trial team back in Iowa three decades ago. His three teenage daughters stopped coming to him with their problems. Somewhere in the fog of his fight for democracy, they thought he had stopped listening to them. He was consumed by feelings of abandonment by friends and never-ending political fights with fellow Republicans.

His wife confronted him in the kitchen the morning after his friend's funeral in early May 2022.

"You have to go to therapy," Pam Gates, 51, recalled telling him. They had planned to travel once she retired, but she couldn't imagine spending so much time with the person he'd become. She knew being in politics required sacrifices, but this was too much.

"I will forever love you, but this angry, angry person who doesn't listen, who is so under pressure constantly, isn't someone I like right now. The person I like and the person I love is still there. But the person I live with every day is someone I don't even recognize."

He'd experienced many devastating moments since 2020, but this one hurt the most. He called the county's benefits department and soon after, described the state of his health in an online assessment.

"I'm an elected official who has experienced a significant amount of death threats since the 2020 election and also have had many other elected officials from my own party who have attacked me and questioned my integrity," he typed.

"With COVID subsiding, I have started to attend public functions where I've seen some of these individuals and I have reacted very negatively and gotten very angry. I have also been interviewed by many journalists over the last 16 months [about] this issue and have become very sad and very angry during these interviews, sometimes even crying."

Bill Gates reacts to commentary from a self-described “election denier” during a Feb. 13 moderated discussion in Phoenix between election officials and Arizona voters who are suspicious of the voting process. (Rebecca Noble for The Washington Post)

The threats started even before the presidential election, during the summer of 2020, as the number of deaths from covid-19 mounted. The five-member county board, which is responsible for managing public health emergencies, had enacted a mask mandate that enraged far-right activists who viewed it as a violation of their individual liberties.

One afternoon, Gates pulled into his driveway and checked his mailbox. He found a flier with his face superimposed on a body holding a whip.

"This is your neighbor Republican Bill Gates, the District 3 Maricopa County Supervisor," it read. "He thinks he's your master. . . . He wants you MUZZLED."

The fliers had also been distributed to his neighbors. He and his family suddenly felt unsafe in their own home.

One daughter asked how people with such vicious tactics knew where they lived. Another, who is Ugandan and Black, was devastated that the flier equated her father's support of the mask mandate to slavery. His third daughter was unable to sleep that night and many more nights to come.

"That's when everything changed," Gates recalled.

He and his wife told the kids not to open the front door and to keep a close eye on their surroundings. Gates began fielding phone calls and texts from neighbors about suspicious cars and strangers outside of their home, including one who took photos. When far-right activists posted his personal information online that summer — and several more times over the next two years — he or his wife would rush home to ensure the girls were not alone.

The attacks on their sense of security only worsened during the 2020 presidential campaign that fall.

"We felt sort of violated," he recalled.

It became difficult to recognize his political party. The hate he was witnessing was rooted in anger and grievance, not policy debates or productivity.

As Gates ran for reelection himself, he kept tabs on Trump's attacks on mail-in voting and refusal to commit to a peaceful transfer of power, should he lose. Gates thought it was bluster.

In the days after the election, when it became clear Joe Biden would win Arizona, Trump's allies tried to persuade Gates and four other county supervisors to stop counting votes and delay certification of the results. The board did neither and soon faced an avalanche of emails and phone calls from the president's supporters to probe claims, including that large numbers of ballots had been cast on behalf of dead voters and that equipment used to count ballots was compromised.There was no evidence to support either theory.

Gates and the other supervisors said they trusted the results and went beyond what had ever been done to ensure they were accurate. When the board met in late November to accept the results, Gates compared their constitutional duty to uphold the election results to the experience of his grandfather, who "went to Europe to fight for democracy" during World War II.

Their duty complete, Gates figured the focus would shift.

But Trump and his allies continued to search for ways to change the results, and Maricopa County, one of the largest voting jurisdictions in the nation, became central to conspiracies about Trump's loss. The GOP-led state Senate soon subpoenaed ballots, voting equipment and reams of other information.

As members of Congress gathered in Washington on Jan. 6, 2021, to certify the 2020 election, about 1,000 Trump loyalists protested outside of the state capitol in Phoenix, where they erected a guillotine and carried rifles. Gates watched on television in disbelief as rioters climbed the U.S. Capitol steps and pounded their way inside. What he had mistaken as tough talk was actually the impetus of a violent attempt to overthrow the government.

Gates worried his family may not be safe in their home. He had been labeled a "traitor" and worried a mob might come for him.

"We knew we were ground zero" in Maricopa County, he recalled.

He booked a rental home for what he and his wife called a family "staycation." But his daughters knew they were hiding out. He worried about what this traumatic experience was doing to their childhood. But he hoped the attempted coup would be a wake-up call for leaders in his party who had endorsed or even echoed Trump's rhetoric.

In the weeks that followed, strangers attacked him and his family on social media. They checked in on each other frequently, and altered their schedules so they weren't alone for extended periods. Gates and his wife made sure their close friends had their daughters' phone numbers in case they needed help.

In that political climate, state Senate Republicans threatened to hold the county board in contempt for not turning over all of the 2020 election material they had subpoenaed, including ballots county leaders didn't think they could lawfully release.

The supervisors prepared to be perp-walked and jailed. Gates worried what the vote would mean for his family, his law license and his reputation.

"He personally had come to terms with the decision that his oath of office was what was most important," his wife recalled. "And if that meant his incarceration, that's what it meant."

He worked the phones in search of allies. Twitter filled with an avalanche of vitriolic posts demanding his arrest. "Corrupt dirtbag pedophile supporting maggot," one read. "You don't speak for REAL CONSTITUENTS," read another.

The state senate vote was planned for Feb. 8, 2021. Gates went to the state capitol to lobby lawmakers, then prepared for his arrest.

He texted his family: "I love you guys more than you can imagine. I'm sorry I have put you through all this. Just remember that it is always right to do what's right. We will get through this. Thanks for keeping me strong and loving me through all this."

His daughters had been frantically checking their phones for an update and interpreted his text as news that the Senate had held him in contempt. One daughter collapsed in a high school hallway. Another, who had just finished an Italian class at an out-of-state college, began sobbing.

But the Senate had not yet voted. Gates, meanwhile, gave his chief of staff the passwords to his phone and social media accounts. He recorded a video to be posted after his expected detention, explaining that the county could not legally give ballots to the senate without a court order.

Bill Gates, center, greets Sándor Berki, a Hungarian member of Parliament, in Phoenix. (Rebecca Noble for The Washington Post)

As Gates holed up in his office to watch the senate proceedings, he got an email from a key Republican lawmaker who decided to oppose the resolution, a defection that derailed its passage.

Gates texted his family that he wouldn't be held in contempt, after all.

His wife replied: "Thank god."

The online harassment became a part of Gates' routine. It spiked when he appeared at news conferences and when new versions of conspiracies about Trump's loss spread online. He stopped attending political meetings in his district, finding it unproductive to engage in distortions of truth.

Gates kept waiting for Republican officials who had been hesitant to speak up to finally do so. But most never did.

During the spring of 2021, the state Senate obtained a court order for the ballots and election equipment, which the board handed over. Lawmakers then commissioned a review of 2.1 million ballots cast by voters in Maricopa County, hiring a Florida-based cybersecurity firm with no experience in election auditing. Top Trump boosters and conservative influencers traveled to Phoenix to watch the review, which had no power to change the outcome and was merely a political exercise.

It unfolded inside an old coliseum that Gates could see from his office window. It's where he had watched the Phoenix Suns play basketball as a kid, and later, had taken his own girls for the state fair. Now, he thought it was sullied and should be torn down.

By September 2021, the review was complete, and though it was faulty, it concluded Biden had won.

Yet, within days, the Republican state attorney general, Mark Brnovich, launched an investigation into the county's administration of the election, including issues raised by the Senate's review. The probe carried a new risk: indictments.

In 2022, Gates became chair of the board of supervisors and began preparing for the midterm election.

Crucial seats would be on the ballot, including for U.S. Senate, governor, attorney general, secretary of state and all 90 legislative seats. Nearly all major Republican candidates campaigned on the fictitious notion that Trump had won the 2020 election. Kari Lake, the Republican gubernatorial candidate, proclaimed Biden an "illegitimate president" and said Gov. Doug Ducey (R) should not have certified the election results.

That spring also brought the unexpected death of Gates' close friend, Allister Adel, who was the Republican county attorney. Under the dome of a Catholic church, Gates eulogized her as a dedicated mom and public servant. As he spoke, he had a hard time meeting the eyes of many of his old friends gathered in the pews.

It was later, at her funeral reception, that he struggled to control his anger as people around him struck up small talk. Why, he wondered in loops that played in his mind, had they stayed silent?

Then one prominent Republican casually said he found election denialism was "all very boring." Gates saw red. "F--- you," he thought.

Suddenly he was ranting, and his wife was trying to pull him back from the brink.

In May 2022, Gates had his first meeting with a therapist.

"I was embarrassed to call it PTSD," he recalled telling her. No, she replied, that's what you're experiencing.

He talked about his feelings of betrayal and the physical manifestations of his emotions. The hate from critics triggered insecurity and anger, causing his blood pressure to rise, headaches, anxiety and insomnia. He learned that he operated best through acts of affirmation and encouragement — the opposite of the disparagement he received on social media and at many political gatherings.

"I'm not the smartest guy," he said. "I'm not the most dynamic speaker. But I was always, like, honest. I had integrity. They've taken that away from me forever."

His therapist offered coping mechanisms, like breathing exercises and letting go of things he couldn't control.

He remembered asking her: "How am I able to go back out there and do my job and be a good public servant and represent my constituents and not fly off the handle or be bitter?"

Gates felt himself turning a corner, and his family did, too.

He stopped caring so much about how others viewed him and tried to not obsess about friends who weren't coming to his defense. He reduced his time on social media. He listened to his wife and daughters more attentively, and forced himself to be more present during dinnertime conversations. He was less angry. He found himself cracking jokes and laughing again.

He also realized that he wasn't alone in his experience.

At a conference for election officials in Colorado that summer, he talked openly about his struggles with election denialism and misinformation. Afterward, a county elections manager approached him, and the two were soon discussing their shared psychological stressors.

"I didn't feel alone," said Stephanie Wenholz, who works in Mesa County, Colo. "I felt connected and empowered to go up there and say, 'I am with you.'"

Gates has told other election officials he is in therapy and has often encouraged them to seek treatment.

Before 2020, discussions at gatherings like the one in Colorado rarely strayed from technical procedures, like processing ballots or maintaining voter lists. Now they are a forum to share stories of personal suffering, said David Becker, who heads the nonprofit Center for Election Innovation & Research and has for years attended the conferences.

"Now they're almost group therapy sessions," said Becker. "It's the opportunity for these people to get together with their support network."

Meanwhile, Gates and his colleagues were preparing for another election. He channeled his anger into aggressively debunking information, demystifying the voting process and trying to protect voters from intimidation.

"This was my chance to say the truth and to show people that we were doing things right and that we're good people," he said.

That fall, his therapist reached out with reminders: Other people's opinions didn't define his reality. Positive thoughts cultivate positive actions. Overthinking a problem wouldn't solve it. You cannot make everyone happy.

Gates felt good and was busier than normal. He skipped therapy sessions.

Within minutes of the polls opening on Election Day, there were reports of problems with the printers that produce ballots. Conspiracy theories spread, and Gates again found himself under attack. His wife knew the drill. She packed a bag and they fled their home.

As polls closed that evening, Gates, election workers and reporters from all over the world were sequestered in the vote-counting center. Drones and a helicopter flew the skies and police on horseback patrolled the roads. It felt like a war zone.

Gates and election officials faced scrutiny and ridicule about the equipment failures. Every few hours, he stepped before the cameras in the lobby and took reporters' questions.

That night and in the tense weeks that followed, he sometimes felt caged. "Guys, I just need a few minutes," he remembered telling the team.

Breathing exercises and prayer kept him calm, along with pacing around a conference room. He kept reminding himself that he was acting with integrity by accepting responsibility for mistakes and helping the public understand the vote-counting process.

In January, he relinquished his chairmanship and passed the gavel. Tension in his body fell away.

But Gates could not escape his struggles.

He's back to attending regular therapy sessions and accepting his status as an outsider in Trump's Republican Party. The attorney general's investigation found nearly all claims of malfeasance were unfounded, and the probe ended this year.

He's making amends with old friends he felt were disloyal to him, an important step in the long process of healing.

Now when Gates' critics call him a traitor, he reminds himself that their opinions are a reflection of them, not him. But that's often difficult — especially as the nation prepares for another presidential election and as Trump continues to dominate Republican politics.

Just the other day, a worker came to his home to fix a leaky pipe and wore a red "Make America Great Again" hat. Gates felt anger swelling in his chest.

"It was a trigger to see that hat in my house," he said.

Gates left the room and took some deep breaths.