Tim McLaughlin keeps the American flag in a folder in his basement. (Cheryl Senter/for The Washington Post)

CONCORD, N.H. — Twenty years ago, Tim McLaughlin’s flag briefly came to symbolize victory in Iraq, and the hope that U.S. military power might democratize the Middle East.

McLaughlin was a young Marine Corps officer whose platoon was among the first American units to reach central Baghdad’s Firdos Square. He and the other Marines were met by a few dozen Iraqis who set out, using a sledgehammer and rope, to tear down a 40-foot statue of Saddam Hussein. The Iraqis’ efforts stalled.

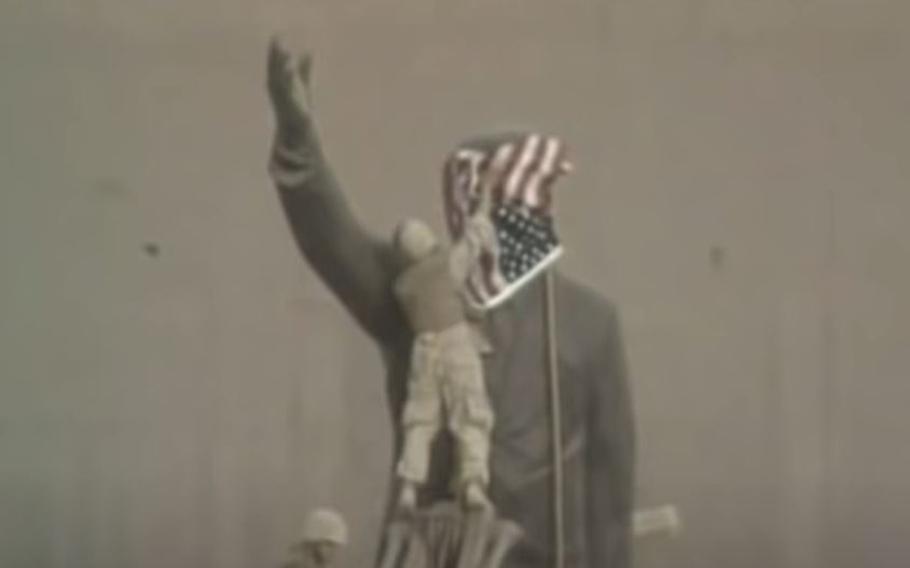

Eventually a Marine vehicle equipped with a giant crane was summoned. Tens of millions of people watched worldwide as McLaughlin’s American flag was briefly draped over the statue head of the overthrown dictator. The Marine vehicle’s engines roared and broke the statue off at its shins.

The events of April 9, 2003, seemed to validate Washington’s promise of a quick, righteous victory and Americans’ expectations about how wars should end.

“Breathtaking,” Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld called the scene from the Pentagon. On cable, news commentators compared the toppling to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Iron Curtain.

Images of the U.S. flag atop the statue in Firdos Square lived on as a reminder of America’s rush to war and the hubris of its leaders. (From YouTube video/AP)

In the months after McLaughlin returned home from Iraq, the war morphed into a grinding insurgency, and the images of his flag atop the statue in Firdos Square lived on as a reminder of America’s rush to war and the hubris of its leaders.

To see the flag today, follow McLaughlin down a dozen steps in his New Hampshire home, past pictures of his smiling boys, piles of old suitcases and his wife’s childhood bicycle.

“The things that a 45-year-old man picks up along the way,” McLaughlin said, gesturing to the junk.

Light streamed through a basement window that McLaughlin recently broke while playing ball in the yard with his two boys, ages 8 and 5. There, in the basement’s back corner, packed away on a metal shelf next to his old Marine Corps uniforms, sits the flag.

As he headed off to war, McLaughlin imagined he would take a picture with the flag somewhere in Iraq that he could show his future kids and grandkids; a simple reminder that he had served and fought.

“In my 25-year-old Marine Corps head, it made sense to me,” he said.

Now McLaughlin is a partner at a law firm, a husband and a father to two boys who are at the age where they still want to be just like him. He pulled the American flag, folded in a neat triangle, from a brown accordion folder.

A war launched 20 years ago to topple a dictator and spread democracy has left him with questions: What does he do with the violent, traumatic memories from his time in Iraq? How does he talk about his war with his sons, who are just beginning to ask about it? How does he explain why his hands still shake when he thinks of it?

McLaughlin had commissioned as an officer in the Marine Corps in 2000 for all the typical reasons. “Some sense of duty, some sense of needing to pay for college, some sense that other family members have done this,” he said.

Tim McLaughlin became an officer in the Marine Corps in 2000 and was part of a platoon that was among the first American units to reach Firdos Square. (Tim McLaughlin)

He was a new lieutenant in the Pentagon on the morning of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and had been running on the National Mall when he saw a black billow of smoke rising from the wreckage. He raced back to help.

Soon after, a friend of McLaughlin’s sister-in-law purchased the flag for him at a U.S. Capitol souvenir shop.

In early 2003, he stuffed it into his green duffel and headed off to war in Iraq. His thoughts at the time had little to do with foiling another terrorist attack, finding weapons of mass destruction or liberating oppressed Iraqis. He had too many other things on his mind. He and his platoon sergeant were responsible for four tanks and the lives of 14 other Marines. McLaughlin’s biggest worry as he crossed into Iraq on March 21 was that he might make a mistake that would get someone killed.

He tried to take photos of the flag a few times before he reached Baghdad. His first attempt was disrupted by gunfire. A second try failed when a fellow Marine saw what he was doing and jokingly ran over the flagpole that McLaughlin had found.

After three weeks of little sleep and near-daily battle, McLaughlin and his platoon reached Baghdad. Saddam’s government had collapsed, but the fighting was ongoing in parts of the Iraqi capital. His unit’s mission was to help secure the Palestine Hotel and the scores of international journalists staying there.

At 4:30 p.m. dozens of Marines arrived in the deserted square. Soon they were greeted by the journalists from the Palestine, peace protesters, and Iraqi citizens who approached cautiously at first and then began swarming their vehicles. In his green field notebook, McLaughlin described the scene as “pandemonium.”

An Iraqi man who spoke some English asked Gunnery Sgt. Leon Lambert, who commanded the crane-like vehicle, to pull down the statue of Saddam. Lambert relayed the request to his commanders. “Not what we’re here for, Gunny,” he recalls being told.

He gave the Iraqis a sledgehammer and rope. A few of them, including a former Iraqi weightlifter, took turns hammering at the statue’s base. Others climbed a rickety ladder and draped the rope around its neck, but were making little progress.

The senior officer in the square took note of the large number of journalists and decided the Marines should help. He ordered Lambert to tear down the statue. Someone told McLaughlin to find his flag, which made its way to Cpl. Edward Chin, who was in the process of climbing the crane. The 23-year-old Brooklyn native draped the flag over the statue’s face and tied a heavy chain around its neck. McLaughlin watched from the ground and snapped a picture with his disposable camera.

Soon the Iraqis were tearing the statue apart and beating on the statue’s severed head with their shoes.

McLaughlin’s first indication of the moment’s power came from a Times of London reporter who found him by his tank a few hours after the statue had fallen. The images of his flag atop the statue had caused a stir among some of the Iraqis in the square and upset some senior Pentagon officials, who were trying to send the message that U.S. troops had come to liberate Iraq, not occupy it.

Tim McLaughlin’s son Roland, 8, makes his way downstairs. McLaughlin hopes to shape his two sons’ understanding of his role in Iraq and its profound effect on him. (Cheryl Senter/for The Washington Post)

The reporter advised McLaughlin that the world had seen his flag and that the moment would be perceived in “a million different ways.” McLaughlin, who had been focused on blocking possible suicide bombers from entering the square, thanked him and stuffed the flag in his tank.

Most of the coverage in the United States, though, was triumphant. Pictures of the falling statue and McLaughlin’s flag blanketed the front pages of newspapers. Researchers from George Washington University found that Fox News replayed footage of the statue’s fall every 4.4 minutes on April 9. CNN was close behind at 7.5 minutes.

Much of the focus in the days that followed was on Chin, who was interviewed by the “Today” show and CNN’s Larry King. The networks tracked down his mother, an immigrant from Myanmar who had settled in Brooklyn and recalled how he had played with GI Joes as a child. She said she was “so proud, so very proud” of her son.

McLaughlin did a few interviews as well and then turned back to the war and leading his platoon. “Spoke with SSgt Pop about the day,” he wrote in this green field notebook, referring to his platoon sergeant, Nick Popaditch. “Historic. Went to bed + stood watch.”

Three days later McLaughlin’s company was ambushed while guarding the Water Ministry. “Cpl. Gonzalez killed,” he wrote.

The first moment McLaughlin had to reflect on his war came at a big logistics base south of Baghdad, where he waited with his tank to return home. He had been in Iraq about six weeks.

How troops saw the war in Iraq was often defined by their job and the weapon they wielded. Some glimpsed the fighting through the window of a speeding Humvee. Others saw it over the iron sights of an M16 rifle. McLaughlin’s view was focused and magnified by the optics on his Abrams tank, which often allowed him to see the facial expressions of enemy soldiers and civilians.

He catalogued his thoughts in his green field notebook. McLaughlin’s first entries describing the killing he took part in are clinical and sparse. “Company volley into buildings. Killed 4 soldiers trying to run away. Let 1 run for a while then killed him, legs first, then as he tried to crawl,” he wrote.

A few pages later he recalls a car that swerved and struck a tree amid a flurry of machine gun fire. “Civilian shot 5 times in back and legs,” he wrote. “Continued progress to Afak.”

In the latter passages, the Iraqis are no longer just enemy, but human beings caught up in a maelstrom partially of McLaughlin’s own making. He recalls a man on a bicycle and his dog “stuck in the middle of a Cobra [helicopter] attack ... trying to get away.”

He remembers a woman sitting on the side of the road with a “look of tired indifference ... as if she’d seen this before and would see it again.”

He recounts firing three rounds at a dump truck that ignored the Marines’ orders to stop and that they worried might be loaded with enemy or explosives. Instead, the cargo was “20 women, children and fathers” who emerged screaming. “By the grace of God no one died,” McLaughlin wrote, “although one guy had a new hole in him and tons of blood. He lived though.”

McLaughlin studied Russian poetry in college, and some pages of the journal include snippets of verse. “I stare and smile, hidden from the rest of the world is a place I’ve just been,” he wrote.

By mid-May McLaughlin was headed back to the United States on the USS Boxer, where he had access to the internet. It was his first opportunity to see the war through the eyes of people watching it in the United States. Media coverage of the war had dropped off precipitously after Saddam’s government fell.

McLaughlin typed “Iraq War” into a search engine. Up popped pictures of his flag, the statue and Firdos Square. “That’s how people experienced this,” he recalled thinking. “That’s how people are internalizing this.” He checked the Red Sox’s record. And he had his first postwar nightmare of the sort that would recur several days a week for the next 18 years. In that first dream, he’s a small boy having a sleepover at his best friend’s house in Laconia, N.H., when faceless invaders burst through the sliding glass doors overlooking Opechee Bay and kill his friend. He tries to stop them, but he can’t.

In 2009, the National Museum of the Marine Corps and McLaughlin messaged about donating his flag. “It is a remarkable bit of history,” a museum official wrote him. At the time, the flag was stowed in a safe-deposit box belonging to McLaughlin’s father.

McLaughlin asked a couple of questions about how it might be displayed and then decided the best place for it was in his basement. “It has meaning for me, which is different from its meanings for everyone else,” McLaughlin said of the flag. “And I do not wish it to have all those other meanings anymore.”

Tucked inside the flag is the photograph that he imagined he might someday show his children and grandchildren. Chin’s left hand is resting on the statue’s shoulder, just beneath the flag. Lambert stares up at him from the bottom of the frame, bracketed by the outstretched arms of a dozen or so Iraqis.

For McLaughlin the flag is a reminder of the people he served alongside and the violence he witnessed, and in many cases caused, both before and after that day in Firdos Square. “I remember, like a movie, when I close my eyes, almost all of those experiences,” he said.

Tim McLaughlin, his tank and his platoon in 2003, around the time that U.S. forces invaded Iraq. (Tim McLaughlin)

McLaughlin spent another three years in the Marine Corps but didn’t deploy again. His experiences from Iraq followed him to law school at Boston College and then to Bosnia, where in 2008 he was assigned to a team prosecuting war crimes from Srebrenica, the site of a massacre that killed 8,000 Muslim men and boys more than a decade earlier. “I just wanted to be and exist in a place where I could see how the world puts itself back together,” he said of his time in Sarajevo.

By 2011, McLaughlin was a lawyer at a big corporate firm in Boston and the president of Veterans Legal Services, a group that provides free advice to low-income and homeless veterans. His wife, Katherine, worried about his nightmares, which were vivid and frequent. She had known him since college as a careful and patient listener. Increasingly, he seemed irritable and detached.

“Are you OK?” she often asked.

He took prescription medicine to help sleep at night but believed he could manage his symptoms. “I Superman-ed,” he said. “As a Marine Corps officer, we don’t have problems. That’s just the way it is.”

In June 2020, the pressure of the pandemic, his law career, fatherhood and the violent nightmares that never stopped became too much to bear.

“I just ran out of rope,” he said. “Whatever additional rope that I had, COVID used up for me.”

He gave his .45-caliber pistol to his brother and began to revisit his war through therapy.

The Marines who were with McLaughlin when the statue fell all see their war and that moment differently. Chin, who had balanced precariously atop the crane, returned to a hero’s welcome. He threw out the first pitch at a Mets game in July 2003 and shook hands with then-President George W. Bush. “I’m just a kid with immigrant parents,” Chin said. “I never expected these things to happen.”

He left the Marine Corps in 2003 and started a family in New York City. As the war dragged on, his doubts about it and about his country’s leadership grew. “Is war ever justified? I don’t think it usually is. It’s something that happens; something the elite want to do,” he said. “Only they know the details or reasons behind it.”

Many of the Marines from Firdos Square moved on to other deployments. In 2004, exactly a year after he watched the statue fall, McLaughlin’s platoon sergeant, Popaditch, was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade outside Fallujah that destroyed one eye and left him with limited sight in the other.

He and McLaughlin were rarely apart on the battlefield during the war’s first months. They remain friends. For McLaughlin, the toppling of the statue was just another day in a very violent war. For Popaditch, it was a defining moment, both for the Iraqis and in his own life. He held fast to the memory through the withdrawal of U.S. troops in late 2011 and their return in 2014 to battle Islamic State radicals who seized large swaths of the country. Popaditch had found meaning and purpose in Iraq. “It sounds weird to say you loved the war,” he said, “but I did.”

In 2021, the crane-like vehicle that toppled the statue was decommissioned and donated to the National Museum of the Marine Corps. The Marines invited Lambert, who commanded the massive machine in Iraq, to speak at its sendoff.

A majority of Americans no longer believed the war had been worth fighting, according to polls. Lambert, a decade retired, still sees it as just. “I don’t care how we got there,” he said. “We belonged there. What they were doing to their own citizens was wrong. They needed help.”

But he also couldn’t stop thinking about how his vehicle had run over the bodies of dead Iraqis on its way to Baghdad in 2003 and how he had begun feeling angrier and more depressed in the years after his second Iraq tour in 2004.

“I have a lot of bad memories,” he said.

Tim McLaughlin’s peace sign on the front of his garage. (Cheryl Senter/for The Washington Post)

Today, McLaughlin lives in a big house at the end of a long driveway. He recently hung an iron peace symbol, about the size of a basketball backboard, over his garage.

McLaughlin stands 6-3 with a mop of hair that hangs over his forehead. He has a quiet manner and a rueful smile. A rescue dog named Waffles follows him from room to room, rarely letting him out of his sight.

On the couch in his living room, McLaughlin opened his green field notebook from his time in Iraq and paused on the list he’d made of the people he saw on the way to Baghdad. The screaming Iraqis in the truck, the man on the bicycle, a family he nearly killed with his tank. His hands began to tremble. Outside, an early spring snow was falling. His boys and wife were playing at the end of the driveway.

“What’s interesting to me is at the time I didn’t realize I was writing down the events that I would be in therapy for 18 to 20 years later,” he said. “That’s basically the list right here.”

At some point on the way to Baghdad, the violence and death caused his emotions to shut down. “For me, the emotional side never got turned back on for 17 years,” he said. “To start them back up again meant dealing with those emotions, which sucks by the way.”

He credits Department of Veterans Affairs therapists and medication with helping him reconnect with the horrible and traumatic events he experienced as a 25-year-old. These days, his nightmares are less frequent. “The VA Vet Center saved my life,” he said. “That’s what they did.”

McLaughlin’s eldest son, Roland, has begun to ask about Iraq, the Marine Corps and what it’s like to be a warrior. Someday he will search his father’s name online and be able to read about McLaughlin’s war, the killing he took part in, and his brief moment of fame with the flag. Before that happens, McLaughlin wants to shape his understanding. He wants his boys to understand the trauma that he carries. He hopes they will see his war as something neither glorious nor ignoble.

His therapist suggested that he try to paint some of his more traumatic memories from the war. Several months ago McLaughlin and his son drove to the art supply store. Roland helped him pick out the materials and prepare the canvas. McLaughlin painted a picture of a burning bus in Baghdad, packed with anguished civilians. The lines on the bus are crisp and clean. McLaughlin intentionally rendered the civilians as blurry and abstract.

“I haven’t told my boys what it is,” he said. “Just that this is something I see.”

Today, the flag seen by millions is in the basement, now rarely seen by anyone. The painting sits on a shelf in McLaughlin’s bedroom closet, where he sees it each morning, next to a photograph of his tank and his platoon.