A view of Earth from the moon in a photo taken during the Apollo 11 mission. (Johnson Space Center/NASA)

Imagine a world where global warming on Earth has meaningfully diminished. Fossil fuels are on the back burner. Affordable renewable energy sources run most of our activities. Oh, and there's a cannon on the moon shooting lunar dust into space to help partially shield sunlight hitting Earth.

That's one eyebrow-raising approach for cooling our planet proposed by a group of astrophysicists in a study published Wednesday in PLOS Climate. The team used computer simulations to model various scenarios where massive quantities of dust (and we mean a lot of dust) in space can reduce the amount of Earthbound sunlight by 1-2%, or up to about six days of an obscured sun in a year. Their cheapest and most efficient idea is to launch dust from the moon, which would land into orbit between the sun and Earth and create a sunshade.

Yes, the idea sounds like science fiction. Yes, it would require (a lot of) new engineering. Yes, there are more feasible climate mitigation tactics that can be employed now and in the near future. But the researchers view this rigorous physics experiment as a backup option that could aid — not replace — existing strategies to help humankind live on a more comfortable Earth.

"We cannot as humanity let go of our primary goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions here on our planet. That's got to be the first job," said Ben Bromley, the study's lead author and an astrophysicist at University of Utah. "Our idea is one — and it's a very, very intensive one — to contribute to climate change mitigation, if we need more time here at home."

Some climate scientists, however, see such projects as distractions from more permanent climate solutions, such as reducing fossil fuel consumption.

This isn't the first idea for a space-based climate solution

The astrophysicists came up with a space dust shield by borrowing concepts from their usual research focused on how planets form around distant stars. Bromley explained that planets form through a messy process involving a lot of collisions, which kick up dust that can intercept a large amount of starlight. So why not explore strategically using such light-blocking dust for Earth's benefit?

The team is not the first to propose using a physical object in space to block sunlight to Earth, which some categorize as solar-based geoengineering. Ideas showed up as early as 1989 when James Early at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory proposed placing a thin, 2,000 km-wide glass shield between the sun and Earth (that's nearly 1,250 miles). In 2006, astronomer Roger Angel explored the idea of sending trillions of small spacecraft with umbrella-like shields to block the sun. In 2012, Scottish researchers investigated blasting off a dust cloud from an asteroid placed between the sun and Earth. Last year, a group of MIT researchers proposed deploying a raft of bubbles that could pop without leaving space debris.

Yet those ideas have run into myriad issues: Too much material is needed. It would require construction in space. It's dangerous. Irreversible.

"The literature around space-based geoengineering now spans more than three decades and is filled with creative, often outlandish ideas," Chad M. Baum, a behavioral scientist at Aarhus University who was not involved in the new study, said in an email. "Some have claimed that seeing these kinds of climate solutions being discussed might bring home the urgency of the situation we are in."

Still, he said such space-based projects to reduce incoming sunlight are "currently among the very least feasible," given the cost and numerous technical, political, social and legal obstacles.

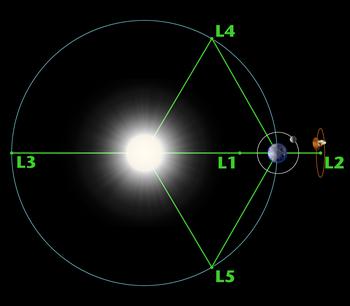

Lagrange points are positions in space where objects sent there tend to stay put. (WMAP Science Team/NASA)

Shooting from the moon

In the new study, the authors concede their idea isn't perfect but say it addresses some problems with previous concepts.

For instance, the amount of material needed to actually shade the sun exceeds 22 billion pounds, which is about 100 times more mass than humans have ever sent into space. Bromley says dust is very efficient at scattering sunlight relative to its size. The team considered different types of dust, scattering properties and size. The team found that aggregates of fluffy and highly porous particles scattered light the best, but they opted for a particle perhaps more easily accessible in space: moon dust.

"We really do focus on lunar dust, just plain old, as-it-is lunar dust, without any indication of changing its shape," said Bromley, who said future moon mining could excavate the dust needed.

Perhaps the greatest challenge is getting the right material exactly where you need it, Bromley said.

In one computer simulation, the team shot lunar dust from the moon's surface toward the sun. Bromley said the device to launch the lunar dust into space could be something similar to an electromagnetic gun, cannon or rocket — picture a T-shirt cannon sending dust into orbit. In the simulation, the dust scattered along various routes until the team found suitable trajectories, which allowed the dust to concentrate temporarily and act as a sun shield. Bromley said the dust would periodically disperse away from Earth and throughout the solar system.

In another simulation, the team shot off dust from a space platform about 1 million miles from Earth. This would be in an area known as L1 (Lagrange point 1), where objects tend to stay put because of equal gravitational pulls between the sun and Earth. This idea required more astronomical cost and effort because they would need a space platform and a dust supply that could be easily replenished.

In either scenario, people on the ground wouldn't be able to see the shield or feel any difference, although some tools would probably be able to detect changes in the incoming solar radiation.

More-realistic climate solutions in development

Report co-author Scott Kenyon said big obstacles in both scenarios would be "the logistics and expense of getting the required equipment to the moon and making it work."

"While we did not calculate these explicitly, we know from the space program that this effort would be daunting," Kenyon, an astrophysicist at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, said in an email.

Baum doesn't normally find dust clouds to be among the most interesting climate solutions, but he thinks the authors "did an admirable job considering many of the different permutations of a potential approach, and specifically looking at the potential orbits."

But he points out issues with the sheer amount of material required — 10 billion kilograms of dust — which the authors say may need to be replaced every few days after the dust streams float away. Also, he anticipates many would take issue with how much "moon engineering" would be required to make the idea work.

Atmospheric scientist Emmi Yonekura, who was not involved in the study and who has proposed using space mirrors to reflect sunlight away from Earth, said there has yet to be a rigorous feasibility study on such space-based climate solutions. However, she said, the advantage to this approach is it requires less spacecraft than previous concepts.

"We haven't solved the climate change problem yet, so these novel ideas are great [for] eliciting reactions from both the public and scientific community," Yonekura, a scientist at the Rand Corp., said in an email. "Solar geoengineering — though highly controversial — does not seem to be off the table, and these new solution ideas help provide alternative approaches that weigh differently in a cost-benefit analysis."

Yonekura said the most feasible solar engineering idea at the moment is to inject gases into the stratosphere. Injecting aerosols could produce a cloud to reflect sunlight back into space to cool the surface below (similar to what happens occasionally in volcanic eruptions), but the technology is years away and could have other issues.

For more radical ideas like the use of space dust, she said such concepts will be difficult to achieve without an international consensus or buy-in from scientific communities and organizations.

It may take a long time to change some scientists' minds. Climate scientist Alan Robock in an email to The Washington Post called solutions such as space dust "quite irresponsible."

"Global climate change from human injections of greenhouse gases is a real problem, but there is a much simpler, safer, and cheaper solution: leave the fossil fuels in the ground and run the world on solar and wind power, of which there is enough to supply power for everyone," said Robock, a professor of climate science at Rutgers University who was an author on the 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change committee that was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

In terms of "climate intervention" projects, Robock said there are a number of more realistic proposals that should receive additional attention. He said carbon-dioxide removal will probably be useful in the future, but is currently expensive and raises potential environmental questions, such as where to bury the carbon. Robock also said more research is needed even with injecting aerosols into the atmosphere, even though it is often discussed as a realistic possibility.

Bromley understands his team's proposal is unusual — but all he wants is the best solution for Earth.

"We're coming in this as people who certainly care about the Earth, care about life here," said Bromley. "I don't know what path people will take, but if [space dust] is one that we view as being more practical, better for humanity, I would love to see this put into operation. It is fascinating."