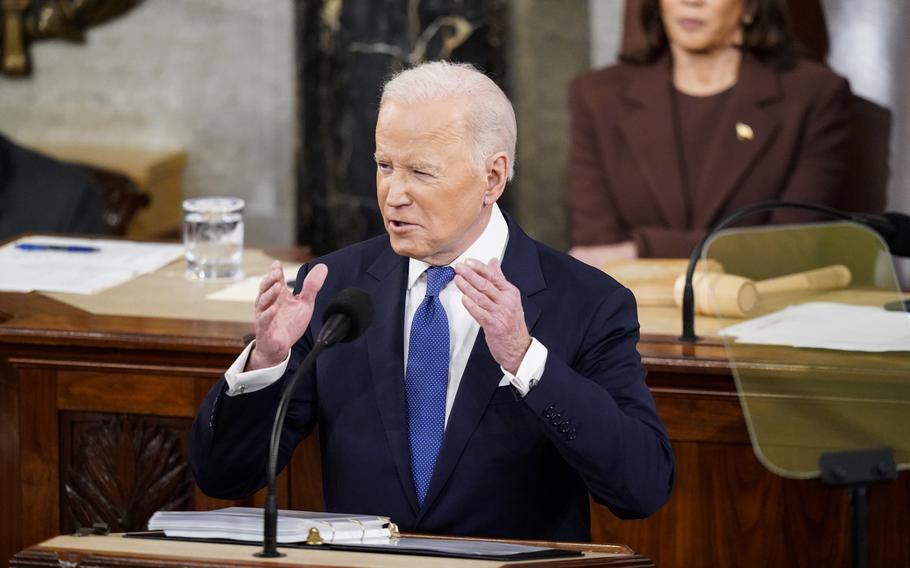

President Biden delivers his State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress on Capitol Hill on March 1, 2022. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

With all the pomp and pageantry surrounding the president’s State of the Union address, one might think its traditions date to earliest days of the republic. There’s the House Sergeant-at-Arms bellowing out the arrival of the president, as if microphones were never invented. There’s the president handing paper copies of his speech to the House speaker and vice president, as if that couldn’t have just been an email.

And, oh God, the applause. The unending waves of applause that double the length of the speech — for the first lady, for whoever is seated next to the first lady, for the troops and the Supreme Court and the Cabinet. The one-party-only applause, the are-we-all-gonna-clap-for-this-oops-I-guess-not applause, and of course the five-minute standing-O’s for every single expression of patriotism.

Weirdly, much of the history behind the State of the Union is modern. Here’s a decoder ring:

1. Why we have a State of the Union

Because it says so in the Constitution. Article II, Section 3, Clause 1 says the president “shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.”

The first president, George Washington, interpreted “from time to time” to mean annually, and “give to the Congress” to mean make a speech before a joint session of the House and Senate. He gave the first State of the Union, then called the Annual Message, on Jan. 8, 1790, in the temporary capitol building in New York. It was 1,100 words long (shorter than this article) and apparently pretty dry: Washington listed things the country should do, like having a joint military, common currency and uniform naturalization procedures.

2. Why the State of the Union is given as a speech

This actually could have been an email.

The second president, John Adams, carried on Washington’s speech tradition, but his successor, Thomas Jefferson, did not, submitting an annual message in print instead. Officially, the reason for stopping the speech was that Jefferson hated anything that smacked of monarchy, but The Washington Post’s Karen Tumulty points out that Jefferson was also afraid of public speaking, and, plus, getting around back then in Washington, D.C., was a mud-caked drag.

For more than a century afterward, all presidents submitted the annual message in text form only, and there is nothing stopping presidents from going back to that tradition, whether by email blast, Twitter thread or in cursive on a parchment scroll.

President Woodrow Wilson brought back the speechifying in December 1913. A former government professor, Wilson thought the separation of powers in the Constitution was a little too strict, and as president he looked for opportunities to increase presidential power and set the political agenda in Congress.

“WASHINGTON WAS AMAZED,” The Post announced the day after his speech, although Wilson had just looked down at his paper and read it out in a monotone. There may not have even been a microphone; according to the House historian, the House didn’t start experimenting with amplification until the 1920s, and it didn’t have a permanent microphone system until 1938.

Every president since — with the exception of Herbert Hoover — has given the annual message as a speech. Franklin D. Roosevelt gave it its modern name, “the State of the Union,” and his successor, Harry S. Truman, gave the first televised SOTU.

On rare occasions, modern presidents have skipped the speech and submitted it in writing; the last one to do so was Jimmy Carter in January 1981, days before he left office. There was technically no SOTU in 2021, since President Donald Trump didn’t give one before leaving office on Jan. 20; Biden’s speech in April 2021 was merely a “joint address.”

3. Why the State of the Union happens at night

For ratings, honey, why else?

No, really. President Lyndon B. Johnson, a master of politics long before he entered the White House, decided to move his speech to prime time so he could speak directly to millions of Americans watching at home (this was back when there were three channels and one couldn’t just switch to “Below Deck Adventure”), who could pressure Congress to do what Johnson suggested. In January 1965, that was the “Great Society” — Johnson’s massive plan for social welfare, education and the arts.

4. Why there’s a rebuttal

Basically because Republicans had a fit when Johnson’s plan worked. They pressured TV networks to televise their response the next year. Two days after Johnson’s 1966 SOTU, Republicans gave a televised response featuring a young congressman and future president: Gerald Ford.

For the most part, the rebuttals tend to be ... weird.

The SOTU’s dignified setting — the House chamber, American flag in the background — and the (partially) supportive live audience naturally elevate a president’s message, regardless of what he says. Then comes the response, with no natural location, no natural audience and a downer of a message. (“What that guy just said? All wrong.”)

Parties have tried to solve for this in a variety of ways over the years, with varying degrees of success, and produced some bizarre performance art along the way.

Sen. Marco Rubio’s (R-Fla.) desperate reaches for a bottle of water in 2013 were probably the most famous, but Democrats have produced some cringey ones, too. In 1972, they aired an hour-long call-in show where lawmakers responded to unrehearsed questions from the public. In 1985, they aired a prerecorded infomercial hosted by future president Bill Clinton, and in 2017, former Kentucky Gov. Steve Beshear responded to Trump’s first joint address in a packed-but-silent diner that was more uncanny valley than aw-shucks.

5. Why the sergeant-at-arms is shouting

It’s the ceremonial job of the House sergeant-at-arms to announce the arrival of the president and other high-ranking officials. (He also has actual duties, like coordinating protocol and security in the House chamber, and serving on the board of the Capitol Police.)

Wilson Livingood served as House sergeant-at-arms for 17 years and shouted the arrival of three presidents: Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama. A soft-spoken man, he once told CNN that for weeks before a State of the Union, he would practice bellowing, “Mister/Madam Speaker, the president of the United States!”

When Paul Irving took over in 2013, he shouted, too; Irving was forced to resign in 2021 after the Jan. 6 riot. Last year, sergeant-at-arms William J. Walker used a concealed microphone — gasp! — and did not yell out Biden’s arrival, which some people did not love. This year, it is unclear what brand-new acting sergeant-at-arms William McFarland will do.

6. Who sits with the first lady (and why they always draw applause)

On Jan. 13, 1982, amid an intense snowstorm, Air Florida Flight 90 took off from Washington National Airport. It struggled to gain altitude and clipped the 14th Street bridge before crashing into the icy Potomac River, killing 76 people onboard and four people on the ground. Incredibly, five people survived, due in no small part to the heroic actions of bystanders. One of them was Lenny Skutnik, a 29-year-old federal worker who jumped into the water and rescued a woman.

What does this have to do with the State of the Union address? Because a few weeks later, President Ronald Reagan invited Skutnik to sit in the gallery with first lady Nancy Reagan during his annual address. Reagan even shouted him out in the speech, calling his actions “the spirit of American heroism at its finest.” Skutnik, clearly embarrassed, received a standing ovation and a salute from the president.

Since then, presidents have invited ordinary Americans who have done something heroic to sit with the first lady during the SOTU. For a long time, those guests were referred to as “Lenny Skutniks,” though few people say that anymore save the most desperate cable news hosts vamping for time.

Skutnik is still alive and probably relieved to have outlived his name being Beltway slang.

7. Why the State of the Union is always “strong”

No matter the speechwriter, no matter the economy or the news of the day, nearly every year since 1983, the president has declared the State of the Union to be “strong.”

In 2022, Biden laid the “strong” on real thick.

“My report is this: the state of the union is strong — because you, the American people, are strong,” he said, then continued: “We are stronger today than we were a year ago. And we will be stronger a year from now than we are today.”