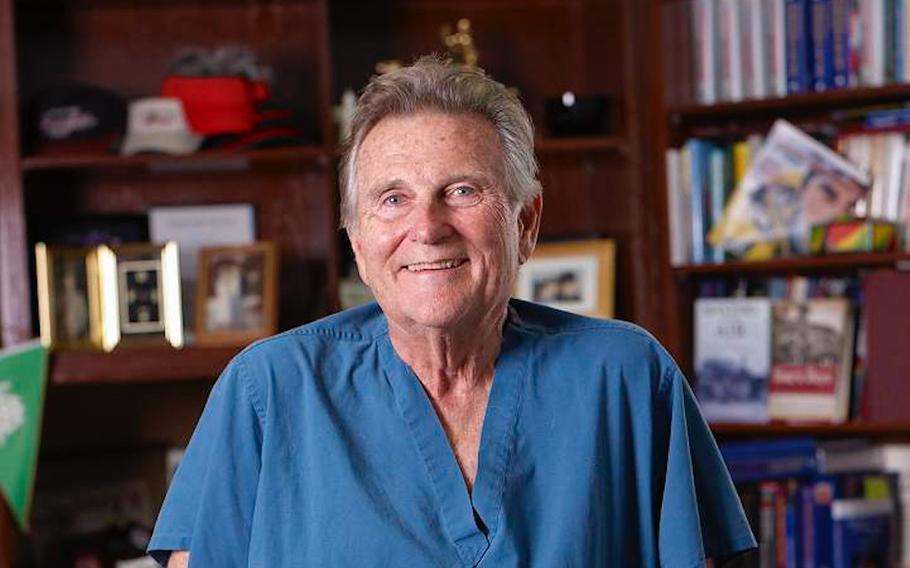

J. Richard Steadman is shown in his office in this undated photo. Steadman, an orthopedic surgeon who founded the renowned Steadman Clinic where many of the world’s top athletes have gone for career-saving treatment, died Friday, January 20, 2023, at age 85. (Facebook)

A top U.S. skier, Phil Mahre was two-thirds through his giant slalom run at a World Cup event in March 1979 when he smashed into a gate. He somersaulted over the snow at New York’s Whiteface Mountain, near a spot where his coach was watching.

“Before he even stopped sliding, he was saying, ‘It’s broken,’” said coach Hank Tauber. Within minutes, Tauber was on the phone with the ski team’s chief physician, orthopedist Dr. J. Richard Steadman.

The next day, Mahre was flown to Steadman’s medical facility in California to repair three breaks above his left ankle and start intensive rehabilitation with the 1980 Winter Olympics less than a year away. “We thought in terms of making him able to return to skiing,” said Steadman at the time.

Mahre won a silver medal in slalom at the Lake Placid Games. For Steadman, who died Jan. 20 at 85 at his home in Vail, Colo., Mahre’s rebound further burnished his reputation as a medical virtuoso.

Steadman’s techniques in surgery and recovery helped extend the careers of scores of top athletes since the 1970s as the chief medical overseer for the U.S. Alpine Ski Team and the go-to doctor for the elite in many other sports.

The Steadman Clinic in Vail — founded by Steadman in 1990 after moving from South Lake Tahoe, Calif. — became a top destination for injured athletes still at the top of their game and hoping to squeeze out some more years of performance. The list includes skiers such as Picabo Street and Luxembourg’s Marc Girardelli; tennis stars Martina Navratilova and Monica Seles; NBA standouts such as Amar’e Stoudemire and Jason Kidd; and football greats including Hall of Fame defensive player Bruce Smith.

“Really all the greatness at the end of my career, I owe to him because he was the one who kept me together,” said Olympic skier Cindy Nelson, who was among the first group of U.S. national team skiers treated by Steadman in the 1970s. Nelson won a bronze medal in downhill in the 1976 Winter Olympics in Innsbruck, Austria, and fractured her ankle the following year. She went on to compete in the 1980 and 1984 Olympics.

Among Steadman’s advances in the 1980s was a knee surgery known as microfracture that sought to harness the body’s regenerative powers and avoid more invasive procedures to repair worn or damaged cartilage. In the approach, the affected area of cartilage is scraped to remove any calcified parts. Then tiny holes are punched into the bone.

This allows the release of stem cells from marrow to stimulate, in many cases, the growth of new cartilage. Many medical studies agree on the efficacy of the treatment, but some papers suggest that the regenerated cartilage can be fibrous and potentially not as durable as original cartilage.

The procedure has been used more than on 500,000 patients per year worldwide, according to the Steadman Clinic, and expanded to other areas such as the shoulders, ankles and hip.

“[The] goal,” said Steadman in 2000, “is to re-create the structures of the knee.”

Steadman’s stamp also is seen in the fast timetable from surgery to rehabilitation steps, particularly for athletes seeking an accelerated return to competition. In the early 1970s, when Steadman began work with the U.S. Ski Team, the common protocol was weeks in a cast after knee surgery.

“That kind of rehabilitation allowed the muscle and joint to deteriorate and left the patient with no chance of a full recovery,” he told the Denver Post.

Steadman encouraged knee flexing and other exercises almost immediately after surgery, and gradually introduced greater levels of resistance on the knee. In some cases, he had skiers add water skiing to their rehab routines.

“The thing that separates success from failure is the way rehabilitation is done. It was tough. It wasn’t just convincing the patients, but the doctors as well,” Steadman said of his early years advocating early physical therapy. “Very few people agreed with that technology.”

John Richard Steadman was born in Sherman, Texas, on June 4, 1937. He graduated in 1959 from Texas A&M University, where he played football for coach Paul “Bear” Bryant during his freshman and sophomore years.

Steadman received a medical degree in 1963 from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas and later served in the Army based in West Germany.

He joined an orthopedics practice in South Lake Tahoe in 1970 and became part of the medical pool for the U.S. Ski Team, at times traveling for events around the world. In 1976, he was named the team’s chief physician. (He was with the team until the 2006 Winter Games in Turin.)

In 1988, Steadman created a sport medicine research group, now known as the Steadman Philippon Research Institute, which has one of the largest databases on cases, treatment details and patient outcomes.

Steadman is also credited with creating several surgical instruments necessary for his new procedures and was involved in work on topical anesthetics and collagen meniscus knee implants. Steadman was a consultant to the Denver Broncos in the NFL and baseball’s Colorado Rockies.

Steadman rarely boasted about his personal connections with top-echelon athletes. In essays for publications such as Newsweek, he could portray himself as just as concerned with sidewalk tumbles and muscle pulls by weekend warriors.

In 1961, he married Gay Lyon Weber. In addition to his wife, survivors include two children, Lyon Steadman and Liddy Lind; a sister; six grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren. The death was announced by the Steadman Clinic, which did not disclose the cause.

Despite his acclaim in the operating room, Steadman said one of his most fulfilling moments came by deciding not to take up a scalpel. In 2001, skier Bode Miller tore his left knee ligaments at a downhill race in Austria. An operation would have jeopardized Miller’s chances of competing in the Salt Lake City Olympics in 2002.

Steadman noted the ACL — one of the critical structures to stabilize the knee — was not completely ruptured. Steadman opted to do a limited surgical intervention to remove damaged cartilage and let the ACL heal on its own.

Miller won two silver medals in Salt Lake City, giant slalom and Alpine combined.

“This was the best surgery I’ve never done,” Steadman said.