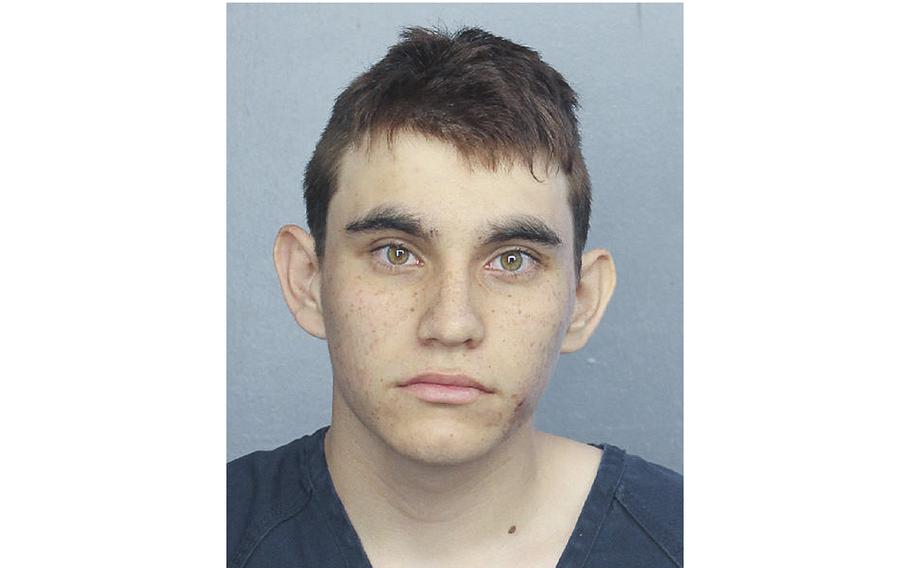

Nikolas Cruz (Broward County Sheriff's Office)

FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. — A jury Thursday recommended Nikolas Cruz get life in prison for killing 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in 2018, sparing Cruz from a death sentence after his lawyers argued he had a troubled upbringing, including allegations that his biological mother abused drugs and alcohol while pregnant.

The sentence caps an emotional three-month trial in which victim relatives and survivors recounted the Valentine’s Day massacre in painful detail. The 12-member jury deliberated for seven hours before reaching their decision in the deadliest U.S. mass shooting case to go to trial.

On each of the counts, jurors found that prosecutors had established aggravating factors including that the murders were especially cruel and heinous — indicating that the case met the threshold for death penalty eligibility. But they also decided that the most egregious elements of the attack did not outweigh the mitigating factors presented by defense attorneys.

As the verdicts were being read, many parents of the victims gently shook their heads. One juror clutched a tissue, wiping tears from her eyes. Cruz mostly stared down at a desk. Later, as victims’ family members left the courtroom, some relatives sobbed and collapsed into one another’s arms. Several lashed out angrily at the jurors, accusing them of too easily buying into the defense’s argument that Cruz suffered from mental illness.

How could mitigating factors apply to “this shooter, who they recognized committed terrible acts - shooting some victims more than once . . . pressing the barrel of his weapon to my daughter’s chest?” asked Tony Montalto, whose 14-year-old daughter Gina was killed in the school. “That doesn’t outweigh that poor little what’s-his-name had a tough upbringing?”

The gunman had already pleaded guilty to 17 counts of premeditated first-degree murder, and jurors had to decide on his sentence for each count. Cruz also wounded 17 other students and school staff members during his rampage in Parkland, Fla., a prosperous Fort Lauderdale suburb bordering the Everglades.

The shooting galvanized students in Parkland and elsewhere to speak out against gun violence, leading to the creation of the student-led “March for Our Lives” gun-control movement. The shooting, which Cruz carried out when he was 19, also accelerated school safety and security measures nationwide and prompted debate over arming teachers in the classroom.

Although the trial was designed to help South Florida heal after Cruz’s crimes shattered families and left Parkland students struggling with lifelong trauma, it also sparked a discussion over capital punishment as well as whether society should show any sympathy to killers who may be mentally deficient due to possible prenatal alcohol exposure.

In an interview with CBS’s Miami affiliate, jury foreman Benjamin Thomas said the decision “really came down to one specific” juror who believed Cruz “was mentally ill.”

“And she didn’t believe, because he was mentally ill, he should get the death penalty,” said Thomas, who said a total of three jurors ultimately voted to spare Cruz’s life. “It didn’t go the way I would have liked, or the way I voted, but that is how the jury system works.”

After the verdict was released, one juror wrote a letter to the judge identifying herself as one of the people who had voted against sentencing Cruz to death. In the handwritten note, she said she’d heard from another juror that some on the panel were accusing her of “having already made up my mind before the trial started.”

“That allegation is untrue, and I maintained my oath to the court that I would be fair and unbiased,” she wrote. “The deliberations were very tense, and some jurors became extremely unhappy once I mentioned that I would vote for life.”

Cruz’s sentencing trial featured weeks of gruesome, emotional testimony that included video of how he wandered the hallways of the school with an AR-15 rifle, shooting some of his victims at point-blank range. Jurors also toured the wing of the school where the attack occurred, seeing classrooms that had largely been untouched in the years since the shooting.

During closing arguments on Tuesday, prosecutors accused Cruz of carefully planning his attack for years, and they said he carried it out with ruthless precision.

Broward County prosecutor Michael J. Satz said Cruz began researching other mass shootings — including the 1999 attack on Columbine High School and a 2007 shooting at a high school in Finland — several years before he carried out his own assault. Cruz also purchased his rifle a year before the attack and spent several months gradually amassing ammunition.

Three days before he walked into the school, where he was a former student, Cruz made a video in which he foreshadowed his plans by vowing to become “the next school shooter of 2018.” Cruz selected Valentine’s Day to carry out his attack, and he moved throughout three floors of the school’s “1200 wing” shooting his victims — at times pressing his weapon directly onto their skin before he pulled the trigger, Satz added.

“The testimony revealed the unspeakable, horrific brutality and the relentless cruelty that the defendant performed,” Katz told the jurors. “This plan was goal-directed. It was calculated. It was purposeful, and it was a systematic massacre.”

But Cruz’s defense attorneys urged jurors to spare his life, describing him as a “brain-damaged, broken, mentally ill person through no fault of his own.”

Throughout the trial, Cruz’s defense attorneys alleged that Cruz suffered from “neurological disorders” related to fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Defense witnesses, including medical experts and some Cruz family members, testified that his late biological mother, Brenda Woodard, was an alcoholic and abused drugs, including crack cocaine, while pregnant with him.

“He was literally poisoned in Brenda’s womb,” Melisa McNeill, Cruz’s lead defense attorney, told jurors. “He was doomed in the womb. And in a civilized society, do we kill brain damaged, mentally ill, broken people?”

To apply the death penalty, the jury had to reach a unanimous decision. Speaking directly to jurors during her closing argument, McNeill pleaded with the jurors to take time in reaching their decision, saying they would have to live with the outcome for the rest of their lives.

“Sentencing Nikolas to death will serve no purpose other than vengeance,” said McNeill, who is a public defender.

Under Florida law for a capital crime, prosecutors had to prove that “aggravating factors” contributed to Cruz’s crimes.

The seven potential aggravating factors included whether the defendant had previously been convicted of a violent felony; whether the defendant knowingly created great risk to a large number of people; and whether a murder was especially “heinous, atrocious or cruel.”

Although Cruz did not previously have a violent criminal record, Satz said the murder or attempted murder of any of the 34 victims qualifies. Prosecutors also argued that Cruz committed his crime during a burglary because he was a former student who was not authorized to be on school grounds — conditions the jury agreed had been met.

In all, Cruz fired 139 rounds during his 6-minute, 22-second rampage. The medical examiner testified that some victims had defensive wounds, indicating they were shot at point-blank range as they pleaded for their lives.

The jury was directed to consider 41 “mitigating circumstances” that should spare Cruz from the death sentence even if they found that aggravating factors were involved. Broward County Circuit Judge Elizabeth A. Scherer said those included whether Cruz received proper mental health care while growing up, whether he suffered from attention-deficit disorder and whether he had been traumatized by witnessing the deaths of his adoptive parents.

The judge also asked jurors to consider whether Cruz “continues to try to educate himself despite incarceration” or remains “loved by people.”

During testimony, Cruz often sat with his head slumped down over his desk with his hands on his forehead. During the most graphic moments of the testimony, parents of the victims at times rushed out of the courtroom in tears. At one point in the trial, one of Cruz’s defense attorneys also cried in the courtroom as Fred Guttenberg described his final words to his 14-year-old daughter, Jamie, before she was killed in the shooting.

But not all relatives of the victims advocated that Cruz receive a death sentence, with even some members of the same family split over the question of whether he should die or spend the rest of his life in prison.

“You cannot say that murder is heinous or unforgivable,” Robert Schentrup, whose sister, Carmen, was killed in the massacre, wrote on Twitter as the trial got underway in July, “while advocating for the murder of someone else.”

“I love but disagree with my son,” replied his mother, April, quoting his tweet. “If police did their job that day, the shooter would’ve been killed. . . . Since they didn’t do what was needed then, let the court get it right this time.”

The Parkland trial was unusual from the beginning, because many mass killers are not taken into custody following their attacks. In Parkland, though, the gunman escaped the school by blending in with other students who were fleeing his carnage, and he was apprehended that same day.

In perhaps the most comparable case, the gunman who killed a dozen people inside an Aurora, Colo., movie theater in 2012 was later prosecuted. The jury convicted that gunman before later deciding he should get life in prison rather than the death penalty.

Much of the Florida case revolved around Cruz’s past. Besides using alcohol and cocaine, Cruz’s biological mother smoked cigarettes and worked as a prostitute during her pregnancy, damaging his brain, McNeill said. She then put Cruz up for adoption, and by age 3, a child psychiatrist told Cruz’s new family that he had severe issues.

His adoptive father died before Cruz reached kindergarten. His adoptive mother called authorities to their home more than 50 times. She never opted to have Cruz committed, his lawyers told jurors, because she would have lost his Social Security check.

Although Cruz’s adoptive family lived in a spacious house, McNeill told jurors that the size of his house should not mask the trauma he endured. Cruz often became so angry that he punched holes in the walls and killed animals, McNeill said.

“Living in a 4,500-square-foot house in Parkland, it doesn’t mean you have a good life,” McNeill said.

But prosecutors countered that Cruz’s upbringing was not as chaotic as defense attorneys alleged. One prosecution witness described his adoptive mother, who died in 2017, as a caring parent. Satz pushed back on the defense’s assertions that his biological mother’s alleged alcohol and drug use during her pregnancy was to blame.

“Whether or not his mother smoked during pregnancy did not turn Nikolas Cruz into a mass murderer,” Satz said. “The defendant had a plan, he discussed it, and he carried it out.”

Prosecutors also contended that Cruz displayed a pattern of “antisocial behavior.” Satz said the gunman had an affinity for Nazi swastikas, drawing them on both sides of the magazine of his firearm and on the boots he wore the day of the shooting. Cruz had expressed “hatred toward women” and had a history of making “hateful, racial comments,” the prosecutor said.

The jury reached its verdict just 15 minutes after it began its second day of deliberations. On Wednesday evening, about seven hours into deliberations, the jury sent a message to Scherer stating, “We would like to see the AR-15.”

The message prompted confusion over whether a weapon could be sent into the jury room. As court officials worked to clarify the matter, the judge dismissed the jury for the day. On Thursday morning, the judge and the sheriff’s department agreed to send the weapon into the jury room. Within minutes, the jury announced it had reached a verdict.

David S. Weinstein, a Miami lawyer and former state and federal prosecutor, said he was “shocked as anyone” that the jury sentenced Cruz to life in prison. But Weinstein said Cruz’s defense team’s closing argument — which asked jurors to consider whether a “civilized society” should execute someone who may be mentally ill — proved to be very effective.

Weinstein said the verdict also highlights the significance of a 2016 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that forced Florida to rewrite its capital punishment statute to require that death sentences be unanimous.

“I think whomever it was, whether it was one or two people, they simply told the rest of them, ‘It doesn’t matter how long we sit here, I am not going to change my vote,’ “ he said.

Several parents were outraged at the verdict, saying the jury’s conclusion disregarded the victims of the massacre. Others expressed concern it might make it easier for defendants in other cases to escape the harshest punishment. Some nonetheless said it didn’t feel right to direct their anger at the jury.

Anne Ramsay, the mother of victim Helena Ramsay, 17, said the verdict left her feeling as though there was “no justice.” But speaking with reporters after the sentencing, she also sought to shift the discussion back on her belief that stricter gun laws could have helped prevent the attack.

“If this murderer had mental problems, he still managed to get a gun,” she said. “He still managed to get an AR-15 to mow down our kids. Why was he allowed to get an AR-15?”

The Washington Post’s Danielle Paquette contributed to this report.