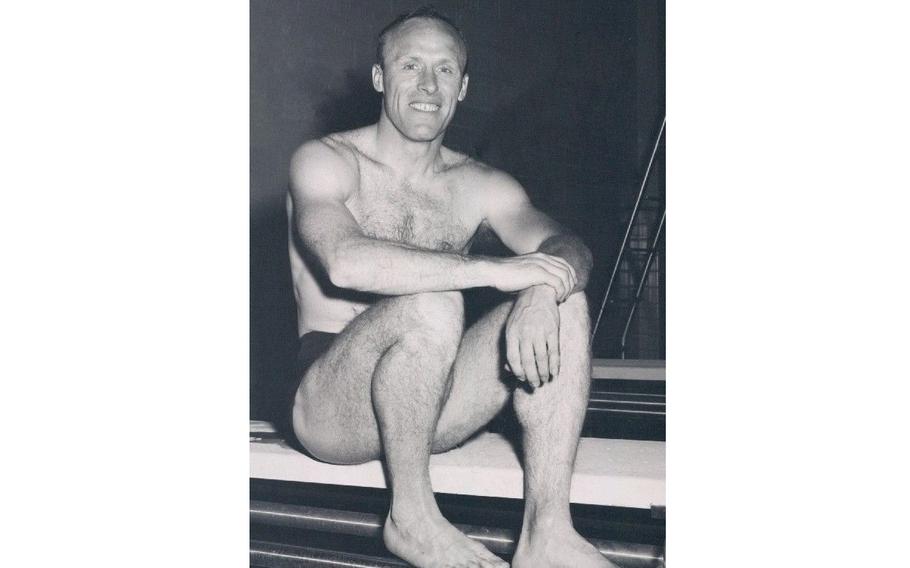

American diving champion, Hobie Billingsley, in 1963. Billingsley, 95, died July 16 at a hospice center in Bloomington, Ind. (Indiana University Archives)

Hobie Billingsley, a national diving champion in college, built the Indiana University diving team into a powerhouse during his three decades as coach. He molded a legion of Olympic divers, trained a generation of instructors and became, in the description of the International Swimming Hall of Fame, “one of the greatest, most beloved diving coaches in the world.”

Billingsley, 95, died July 16 at a hospice center in Bloomington, Ind. His story, as he told it, was one of success beyond anything he could have imagined when he was growing up during the Depression in Erie, Pa., the son of a single mother who nearly placed him in an orphanage because she was too poor to provide for him.

“For the sake of my life,” Billingsley wrote in an autobiography, “Challenge: How to Succeed Beyond Your Dreams,” the downtown Erie YMCA gave him a free one-year membership when he was 7 years old. It was a ticket off the streets and into a world of wholesome fun, of ping-pong with other boys, and cartwheels and handsprings on the tumbling team.

It was also his ticket to hours of practice in the pool, where Billingsley taught himself to swim at age 9 by flapping his arms and thrashing his legs to propel himself across the shallow end of the water. He was essentially an autodidact in diving as well, having used primitive diagrams on a bulletin board at the Y as his only early guides.

As a high school senior in 1943, Billingsley finished third in a national diving championship. He went on to Ohio State University, where he competed under celebrated swimming and diving coach Mike Peppe. Only Peppe, according to the swimming hall of fame, would win more individual diving titles as coach than Billingsley did during his career at Indiana.

He joined IU as diving coach in 1959, working with James “Doc” Counsilman, who led the swimming team. By 1968, Sports Illustrated declared Billingsley “far and away the best collegiate coach in the country.” His divers claimed six NCAA and more than 20 Big Ten team championships, as well as 115 individual national titles, before his retirement in 1989. He was recognized as U.S. diving coach of the year seven consecutive times between 1964 and 1970.

Billingsley developed a methodical approach to diving, an athletic form that Sports Illustrated described in 1966 as “an ascetic, artistic pursuit that is ridden with classical precepts and fixed ideas.” Despite a failing grade on his college physics exam, Billingsley sought to replace those “classical precepts” with Newton’s laws of motion.

“Diving is no longer an art - it is now an art and a science,” he told the magazine. “Newton was the greatest diving coach who ever lived.”

Billingsley was the U.S. women’s diving coach at the 1968 Olympics and the U.S. men’s coach at the 1972 Games. He coached the Austrian team in 1976 and the Austrian and Danish teams in 1980. Among the Olympians who trained and competed under him were Jim Henry, Rick Gilbert, Cynthia Potter, and Lesley Bush and Ken Sitzberger, both gold medalists at the Tokyo Games in 1964. Billingsley also coached Mark Lenzi, an IU alumnus who won a gold medal at the 1992 Games in Barcelona.

Such was his enthusiasm for his athletes, Billingsley recalled, that he once “went to congratulate a diver on winning and ran smack into a wall.”

Hobart Sherwood Billingsley was born in Erie on Dec. 2, 1926. His father was not present in his life, leaving Billingsley’s mother to bring up their two children.

She placed her older son with grandparents, but the grandparents refused to take Billingsley, his daughter Elizabeth Bender said, because he was too “rambunctious.” In her desperation, the mother took Billingsley to a local orphanage, St. Joseph’s Home for Children, and got as far as the steps before deciding that she could not give up her son.

Billingsley spent part of his childhood living in an apartment behind a barber and adjacent to a bar. Noise from the ruckus next door easily passed through the thin wall, Billingsley wrote in his memoir, which was published in 2017. He once overheard a fatal shooting. During the frigid winters, when the wind whipped off Lake Erie and icicles extended down from rooftops like Roman columns, he and his brother scavenged for firewood for their wood stove. Billingsley recalled picking up public food handouts in his wagon or sled.

He was walking home from school one day in a blizzard when a driver, blinded by the snow, struck him. The accident easily could have be fatal but left Billingsley with only “a few stitches” and a headache, he wrote, as well as the conviction that “God had a purpose for me.”

Billingsley’s mother could not afford the YMCA’s $6 annual dues after his introductory membership expired. For nine years thereafter, he sneaked into the club, where staffers either did not know of his status or turned a blind eye to it.

For all the kindness he encountered at the Y, the place did not protect him entirely from the slights that sting long past childhood. Despite his skill on the diving board, the swimming coach declined to take him on a team trip to Buffalo, N.Y., which was also to include a visit to Niagara Falls. The coach, Billingsley wrote in his memoir, “didn’t think I was cut out to be a diver.”

“That kind of rejection was very painful for a twelve-year-old boy,” he wrote, “and it really hurt when I went to the ‘Y’ the next morning and watched all my friends board the bus while carrying their lunches and swim gear and whooping it up. Broken hearted, I stood on the sidewalk crying my eyes out, and waved at them as the bus drove off. That was another painful lesson I would never forget, and I wanted to make sure I’d never do anything like that to anyone.”

He also decided that he would prove the coach wrong and began diving three or four hours a day, he wrote.

After service in the Army Air Forces in the Pacific, Billingsley received a bachelor’s degree in physical education from Ohio State in 1951. He won both the low and high NCAA springboard titles as a freshman in 1945, according to the hall of fame.

He received a master’s degree, also in physical education, from the University of Washington in 1953. After working as a high school gym teacher and swimming, diving and gymnastics coach, he coached briefly at Ohio University in Athens before being hired at IU in 1959.

In addition to his coaching, Billingsley traveled the country performing in comedic water shows with fellow divers Bruce Harlan, a gold medalist in diving at the 1948 London Olympics, and Dick Kimball.

Billingsley’s marriage to Mary Drake ended in divorce. They had three children. Besides Bender, of Bloomington, survivors include two other children, James Billingsley, also of Bloomington, and Nancy Farmer of Clermont, Fla.; nine grandchildren; and nine great-grandchildren. Bender confirmed her father’s death and said the cause was complications from myasthenia gravis, a neuromuscular disease.

Among his other contributions to his sport, Billingsley was the author of a manual, “Diving Illustrated,” that spared future athletes the struggle of learning to dive with nothing more than a few pictures on the wall at their local pool.

He wrote in his autobiography of his abiding gratitude to two men at the YMCA, the director of the boys department and his assistant, who he said were “largely responsible for the person I turned out to be.”

“I was thankful to the ‘Y’ and those men,” Billingsley continued, “for taking a kid like me in who was caught up in the grips of the Depression, or I probably would have ended up in prison.”