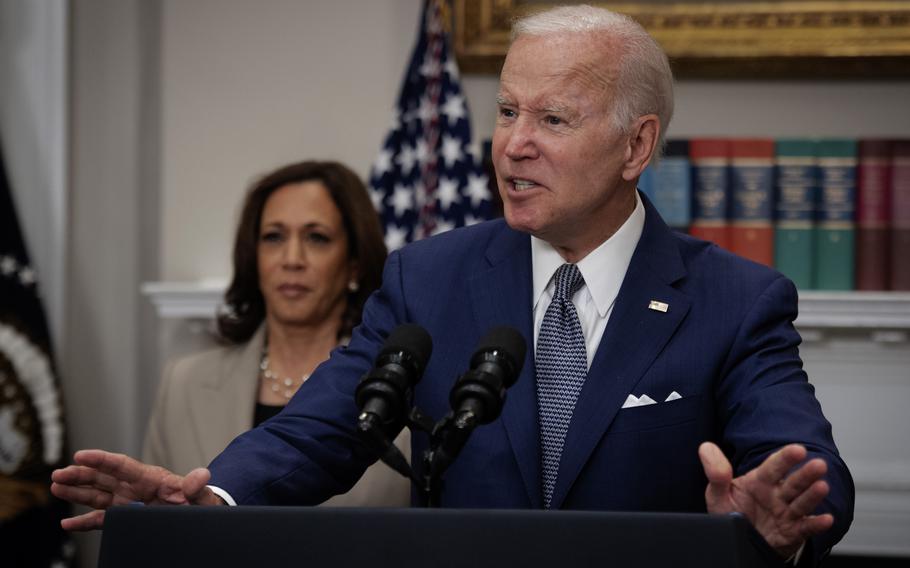

President Biden grows visibly angry while relating the story of a 10-year-old girl forced to travel to another state for an abortion after being impregnated by a rapist, in his remarks before signing an executive order on protecting access to reproductive health-care services. (Bill O’Leary/Washington Post)

WASHINGTON - Two weeks after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, President Joe Biden stood in the Roosevelt Room in the White House on Friday to announce an executive order aimed at preserving, where possible, the right to an abortion. The moment illustrated the tension between the president and a portion of his party's base frustrated by his leadership.

The Democratic left sees their rights being rolled back, whether by the Supreme Court or Republican-held state legislatures, from abortion to guns to voting laws. They see a Republican Party poised to take control of the House and possibly the Senate in the November elections. They want both reaction and action - stronger and more forceful rhetoric from the president and more aggressive steps to counter the right. In their eyes, Biden, who in temperament and instinct is still as much a creature of the Senate as of the executive branch, has not risen to the challenge.

From the White House, there is a somewhat different perspective, that the complaints from progressives are both expected and acceptable, that this is normal buffeting of a president by an activist base in an effort to keep pushing him to do more. But in this formulation, Biden presides over a broader Democratic coalition that includes everyone from Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., on the left to Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., on the right and must never forget the importance of that.

Whatever frustrations are being expressed about Biden's leadership, the view from the White House is that where it has counted most, in Congress, Biden has delivered major pieces of legislation with hopes for something more this summer, and that the president has held together a congressional coalition with fewer defections than either of his two Democratic predecessors, Barack Obama and Bill Clinton. In a 50-50 Senate and a House where the Democratic majority is slender, even a few defections can be deadly, and that is part of the discontent - and disconnect - between the president and his Democratic critics.

The criticisms from the left fall into several categories. One is that Biden has lacked a consistent tone of anger and outrage over what is at risk and what is at stake at an unprecedented moment in American politics. At times he has risen to the occasion. At times, in the eyes of his detractors, he has not.

On the night of the mass shootings in Uvalde, Texas, Biden's anger was palpable, and his language reflected it: "Why are we willing to live with this carnage?" he exclaimed. That rhetoric may have contributed to the passage of the first major gun-safety legislation in decades.

But when a gunman killed seven people at a Fourth of July parade in the Chicago suburb of Highland Park, Ill., his initial words seemed unexpectedly tepid, at least in comparison to those of Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker (D), who gave voice to the fury of many Americans at the epidemic of gun violence.

On Friday, speaking about abortion, Biden attacked the high court's ruling in strong language, calling it "terrible, extreme and, I think, so totally wrongheaded." But while pointed and emotional in his criticism of the justices, the executive order Biden issued fell short of what some advocates had hoped for. Many of these advocates were also frustrated by the fact that the White House wasn't ready with a response on the day of the decision, given that a leaked draft of the majority opinion had been in circulation since May.

That goes to the second area of criticism of the president, which is that he has been unnecessarily restrained in what he has pushed for. That could reflect the real-world politics in which he lives: the knowledge that he and the Democrats have quite limited power to get their way on issues in the Senate and also that some of what he is proposing on abortion won't stand up to the expected legal challenges.

To his critics on the left, he should be more willing to take on the big fights, even losing ones, to put down markers, to show where he is trying to lead, to rally and mobilize voters, to show more explicitly that he understands the feelings and frustrations of many in his coalition. As Faiz Shakir, senior adviser to Sanders, put it: "Show me you're willing to be a disrupter, just as we've seen the right do. Give me politics that animate the fights I care about . . . and give me things I can touch, feel and see. . . . There is a desire to see bold fights and friction."

Ironically, at the beginning of his administration, Biden was being described by some supporters as the boldest Democratic president since Lyndon B. Johnson, perhaps since Franklin D. Roosevelt. He signed the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, which put money in people's pockets, and later won bipartisan support for a $1.2 trillion infrastructure package.

He also pushed for the multibillion dollar Build Back Better bill, with money for social programs and funding to combat climate change. It was with that bill, which stalled after months of negotiations, that the momentum was broken, and with that came a rising sense of frustration on the left.

Biden and the Democrats had no path on that bill or voting rights or immigration or much else on the progressive agenda, given opposition from Manchin and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz. But one complaint from the left is that as the legislative process broke down, the president lost the thread of his message, that he was unable to sustain the idea that he has a progressive agenda and goals that match the aspirations of many of the critics in his party.

From the administration's perspective, some of this criticism feels like a repeat of what happened during the 2020 Democratic primaries: that the same people who were critical of him then as not rhetorically strong and not in tune with where his party was, are the ones who are most critical today. In the primaries, Biden fought it out - principally with Sanders - and prevailed; center-left trumping the left. His advisers believe that should suggest that the president's political instincts were sound then and are sound today, that he knows how to calibrate his words and actions, that he deals in political reality.

The counter to that is that the world has changed since those primaries. The pandemic happened. The attack on the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, happened. New voting laws have been enacted in some states. Threats to future elections have arisen. Rulings by the Supreme Court's new conservative majority happened. Mass shootings have continued. People are exhausted and on edge. They ask: Where is the passion, day in and day out, that reflects those changed circumstances and the new threats?

Biden has some obvious goals over the next weeks as the Democrats head toward the November elections. One is to win passage of a package that could lower the price of prescription drugs and possibly raise taxes on the wealthiest Americans. Negotiations continue on Capitol Hill, though administration officials are not in the room in part because of strained relations with Manchin. Friday's strong jobs report gives Biden another talking point, though the combination of inflation and fears of a recession make it difficult to get a hearing on jobs alone.

The second is to use the abortion issue to mobilize voters to turn out in what is usually a low-turnout election. That was Biden's main message on Friday. Though he outlined the elements of the abortion executive order he was signing, his rhetoric focused principally on November - the importance of everyone voting and the consequences of not doing so. He called on women to lead that charge.

Changing laws, he said, requires more election victories, and that in turn demands a big turnout in November. No one can say with any certainty whether the decision to overturn Roe will dramatically change the trajectory of an election in which inflation remains the voters' principal concern and Biden's low approval ratings act as a drag on many Democratic candidates. For some activists that ignores the obvious problem: November is months away; the threats are immediate.

Biden and his liberal critics may never be on the same page. He is who he is and not likely to change. They have an agenda about which they feel passionate and have expectations for what they want in their president. Biden will need as much enthusiasm from his base as possible to boost Democrats' hopes of avoiding big losses in November, which also means as much enthusiasm for him personally as possible. He will be under pressure to lead, and lead forcefully. That's the challenge he asked for when he sought the office.