Oedipus Trilogy book cover. (Theater of War Productions/Facebook)

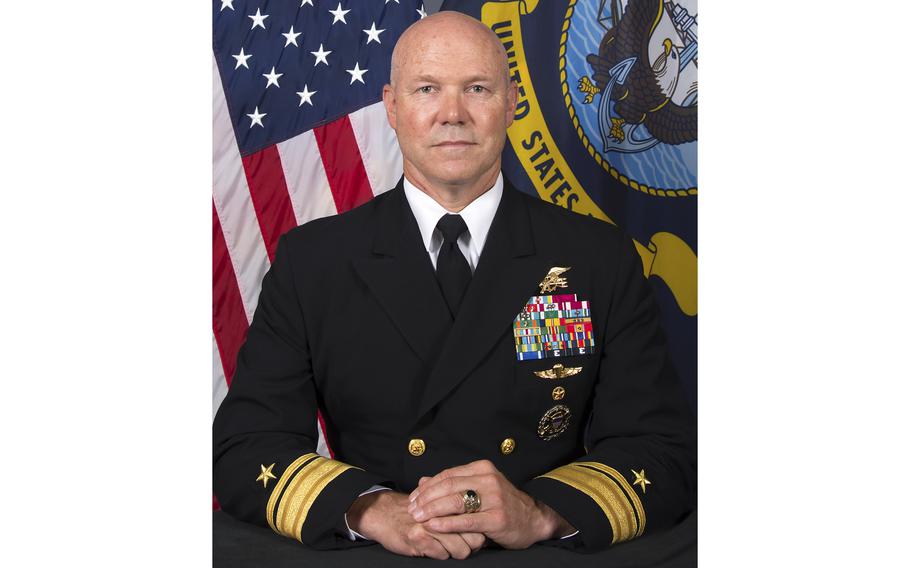

Introducing a Greek tragedy about a soldier who dies by his own hand is not what you think of as normal duty for one of the military's top brass. But that was the mission of Navy Rear Adm. Frank M. Bradley, commander of U.S. armed forces' Special Operations Command Central in Tampa, who recently spoke to a gathering of servicemen and women watching the session online from around the world.

"There's not one of us that hasn't been touched by suicide somewhere in our lives, through our extended families and friends, and as everybody knows, it is a plague that knows no bounds of time or segments of society," Bradley said. "And so, having the opportunity to witness this . . . is a great gift."

Rear Adm. Frank Bradley, Commander, Special Operations Command Central. (U.S. Navy)

The gift itself was not standard-issue, either. A series of scenes from Sophocles's "Ajax" was performed live on Zoom by Theater of War, a 13-year-old professional troupe that recruits actors — some as renowned as Frances McDormand and Bill Murray — to give voice to ancient texts. The nonprofit organization seeks to focus these dramas, like healing lamps, on deep societal wounds. Their specialty is age-old plays that speak to wrenching contemporary issues, such as drug addiction, racial injustice, terminal illness and the climate crisis. Or, in the case of the performance for members of the Special Operations Command Central — which goes by the acronym SOCCENT — the aftershocks of combat.

A 2021 study by Brown University's Cost of War Project reported that suicides by active-duty personnel and veterans "are reaching new peaks." It found that while 7,057 members of the armed forces were killed in military action since 9/11, more than four times as many active-duty members and veterans — 30,177 — died by suicide. The report noted that the military suicide rates now exceed those for the general population, when historically they had been lower.

It was out of concern for this disturbing trend that Bradley, who'd seen other Theater of War productions, brought its work to the attention of Marine Corps Gen. Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr., commander of the U.S. Central Command. He agreed to a series of online training sessions for chaplains and others in Special Operations intended to propel the issue of suicide more emphatically into the open.

"I'm very concerned about the very toxic effects that the battlefield has on people — anybody who tells you it doesn't affect you is wrong. It does affect us all," McKenzie said in a Zoom interview. "In the largest sense, Theater of War is a mechanism to provide a venue for people to talk about their experiences."

Library bookshelves are loaded with plays about war, but opportunities for serious drama and the modern military to engage with each other remain rare. Bryan Doerries, Theater of War's artistic director, had no models to work with when, motivated by a personal tragedy and the desire to respond meaningfully to the war in Iraq, he formed the classically oriented theater company in 2009 with co-founder Phyllis Kaufman, who was its producing director until 2016. The company grew out of his work earlier in the 2000s, when Doerries, a translator of ancient Greek drama, had begun staging readings of the plays in hospitals and elsewhere, and sensed how rawly and powerfully audiences experienced them.

"I began to see that the audience knew more than I did," Doerries recalled, "even though I studied Greek, even though I directed these translations." Having followed news reports about substandard care in veterans hospitals, Doerries turned his attention to military audiences. "It took a year and a half of learning how to talk to people in the military, of making a lot of mistakes, of having doors slammed in my face, of sitting in smoke-filled rooms with veterans," he said.

Eventually, he made inroads, persuading organizers of a conference on combat stress among Marines to allow him to stage scenes from "Ajax" — which tells of a great Greek soldier's decision to kill himself after his humiliation at being denied a ceremonial honor. "A discussion we scheduled for 45 minutes lasted 3½ hours, and had to be cut off at midnight," Doerries said. "And every person who stood up quoted lines from the play as if they'd known it their entire lives."

Given the profound catharsis a piece of relevant drama can summon, it's surprising more theater isn't devised for those who've been to war. Douglas Taurel, an actor and playwright, has learned this over the past several years, as he's traveled the country with his one-man show, "The American Soldier." Based in part on the letters of members of the armed forces, Taurel's 90-minute piece weaves together soldiers' stories from the Revolutionary War to the war in Afghanistan. He's performed it in venues as large as the Kennedy Center and as small as community halls.

"I have audiences where the veterans, they like to sit in the front rows, you know, with their arms folded across their chests," Taurel said of their initial skepticism. By the end of his production — performed in front of an American flag, along with a single trunk full of props — he said many of them are in tears and asking why his play isn't better known. "Some even ask me why it isn't on Broadway," Taurel said with a laugh.

Theater of War has a more therapeutic aim. In its military programming, the company, which relies on foundations and other private sources for financial support, has visited bases all over the world. The pandemic, of course, curtailed its mobility and compelled it to shift to virtual presentations, but the move to digital actually expanded the company's audience. "Zoom was another explosion for us," Doerries said, noting that as many as 20,000 viewers in 82 countries have tuned in to a single event.

In November, the Internet provided what Doerries calls his "digital amphitheater" for the 40-minute presentation for SOCCENT of scenes from the Greek play. " 'Ajax,' " he said in his opening remarks, "was written by a general named Sophocles and performed in the 5th century BCE for as many as 17,000 citizen soldiers, who sat shoulder to shoulder in an ancient amphitheater with the generals in the front row."

In the charged aftermath of the American withdrawal from Afghanistan, a reckoning with the psychological toll of the country's two-decade involvement offered emotional subtext for the session. To underline the issue of suicide, the actors — Alex Morf as Chorus, Glenn Davis as Ajax and Marjolaine Goldsmith as Ajax's mistress, Tecmessa — played out Sophocles's dramatization of the agonizing final moments of Ajax's life, as the indignity of being refused the armor of his dead friend, Achilles, overwhelms him.

"These are the last words you will hear Ajax speak!" Davis cries, before shrieking out a high-pitched death rattle.

"It's over, friends," Goldsmith's Tecmessa declares, upon discovering Ajax's body. "Everything is lost."

"What is it?" shouts Morf.

"Ajax, impaled on his sword," Tecmessa replies.

"He has killed us with this death!" Morf calls out.

After the reading, service members spoke of the familiar signs of suffering that "Ajax" conjured; of the pain of loved ones, who could not fully grasp what occurs to a human on a battlefield. (To protect the privacy of the participants, a spokesman for SOCCENT asked that the audience members remain anonymous.)

One commenter, though, seemed to speak for many when he gave his own eloquent interpretation of Ajax's pain: "His heart was broken from the beginning," he said of the title character. "And I think the entire play is a cascading effect, that Ajax was slipping on a very slippery slope. At the very end, he slips and it's hard to watch because it's real. It is extremely real and it's uncomfortable. But the fact that it is highly uncomfortable is probably the best thing about it."

McKenzie and Bradley acknowledged the value in exposing military men and women to drama that explores the universality of trauma.

"The military has a very almost antiseptic veneer," Bradley said. "We behave with each other in a calm, cool [way] under stress. But you know, deep down, these people are human."