U.S.

He pleaded guilty in terrorism case, did his time and now may lose his American citizenship

The Washington Post December 18, 2021

Abdulrahman Farhane, a Moroccan-born naturalized U.S. citizen, was among scores of Muslims rounded up in a post-9/11 dragnet. (Nadia Sablin for The Washington Post )

NEWBURGH, N.Y. - In the summer of 2018, Abdulrahman Farhane and his family were living together again for the first time since "the problem," their delicate term for the federal terrorism sting that began after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks and led to his decade-long imprisonment.

Farhane's six children, now adults, had grown up with the fallout: FBI agents raiding their apartment in Brooklyn. Long road trips to visit their dad in prison. The soothing words of their mother, Malika, when the stain of the case cost them job opportunities and made them pariahs at the mosque.

The family always maintained that the case was unjust, counting Farhane, a Moroccan-born naturalized U.S. citizen, among those they believe were persecuted in the government's post-911 roundup of Muslims, which often relied on controversial sting operations. Farhane said he pleaded guilty to conspiracy to launder money and lying to agents to avoid the risk of an even longer sentence; he said his attorney had warned him that no Muslim would get a fair trial.

After serving 11 years, Farhane won early release in 2017, and by the next summer, the constant fog over the family had begun to lift. They allowed themselves to glimpse a future beyond "the problem."

Then a letter arrived from the Justice Department, delivering a new blow.

"Dear Mr. Farhane," it began. There was a lot of legal jargon, but the most important part was clear: The government plans to "revoke your United States citizenship."

Farhane's former attorney had not told him that a guilty plea could jeopardize his citizenship under laws that allow the government to reverse naturalization in certain cases. For decades, that punishment has been largely reserved for war criminals - naturalized Americans stripped of their citizenship for lying about participating in atrocities in, for example, Nazi Germany or the Balkans.

Farhane, now 67, was released just as the Trump administration was expanding the practice in overtly political ways, causing alarm among critics who argued that it defied the Supreme Court's view of citizenship as virtually untouchable. In a 2017 bulletin to federal prosecutors, Attorney General Jeff Sessions encouraged stepped-up denaturalization, calling it "a crucial link" in immigration enforcement.

In its first two years, the Trump administration filed nearly three times the average number of civil denaturalization cases opened over the previous eight administrations, according to an Open Society Justice Initiative report, "Unmaking Americans," published in 2019. The report concluded that "such measures are now applied almost exclusively to marginalized communities," in a campaign targeting people based on their race and religion.

"The denaturalization statutes, already heavily flawed, are far too elastic to safeguard the rights of naturalized Americans in the face of this unprecedented and highly problematic new form of targeting," the report stated.

In February, a month after taking office, President Joe Biden issued an executive order on immigration that included a directive for agencies to "review policies and practices regarding denaturalization and passport revocation to ensure that these authorities are not used excessively or inappropriately."

Since then, there's been no word on the status of such a review, immigration analysts say. The Justice Department declined to comment.

To the Farhane family, the letter from the government felt like a trapdoor that dropped them back into their old life of anxiety and uncertainty. Only one of the six siblings, 38-year-old Salah, was willing to speak on the record; the others said they fear backlash or just want to move on. Some are delaying marriage and homeownership until it's clear whether all of them can remain in the United States.

Farhane's fate now lies with a federal appeals court that is weighing his argument of ineffective counsel, an urgent effort to save his citizenship and that of his two children who became citizens through him. It could take months or longer for the court to issue a ruling.

If Farhane loses, the family faces another open-ended separation. If he wins, there's a different risk - a vacating of the 2006 guilty plea would mean the government could prosecute him anew, potentially exposing him to more prison time.

For the family, the complex legal battle comes down to one question: Farhane is an American who has served his time, so why is the government still going after him?

"We're constantly trying to escape that period," Salah said, "and they're constantly trying to drag us back in."

- - -

Farhane's journey from Casablanca to Brooklyn began with serendipity - or destiny, as the family sees it.

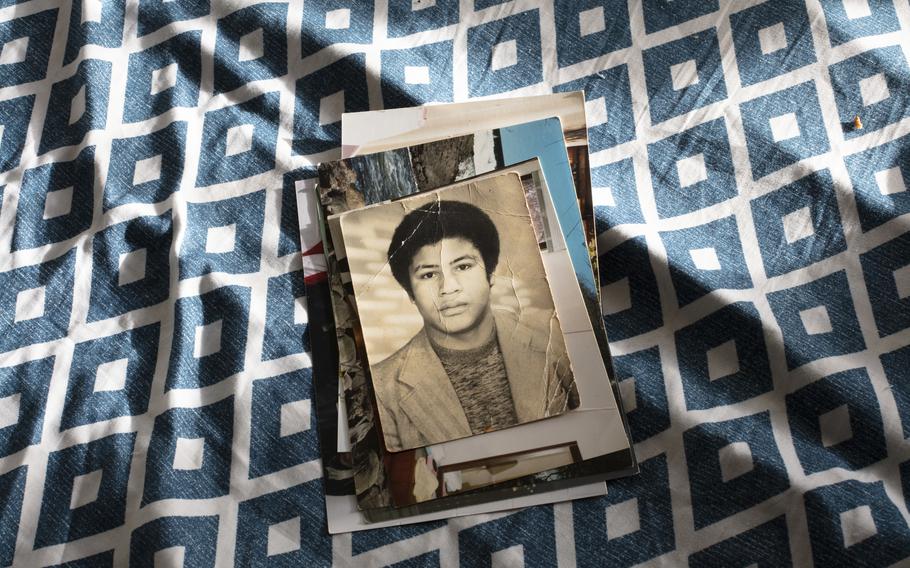

Abdulrahman Farhane in Morocco in 1974. (Nadia Sablin for The Washington Post by Nadia Sablin.)

Farhane's father died when he was young, forcing him to drop out of high school to support the family. He found solace in martial arts, he said, and eventually became a nationally renowned competitor. The Moroccan government offered him the opportunity to travel abroad for training. When he found long lines at the French Embassy, Farhane said, he decided on a whim to try the U.S. Embassy.

He was granted a visitor's visa in 1989 and returned a couple of more times on brief trips in the early '90s. Then, in 1995, Farhane won the visa lottery, a State Department program that randomly selects applicants for green cards, and moved to the United States for good, with his wife and four young children following soon after. In New York, the couple had two more children. Of the four older siblings, two were naturalized through Farhane and are the ones at risk in the pending case.

Within a year of his arrival in 1995, Farhane bought an Islamic gift shop from an Egyptian friend; he sold books and incense to Muslims who frequented a nearby mosque on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn. Photos from the family's early days in the United States show them on strolls and picnics near the Brooklyn Bridge, the kids smiling as they posed next to a Bugs Bunny character or showed off school diplomas.

Farhane said his biggest reason for moving to the States was to give his children the educational opportunities he missed out on in Morocco. His wife, Malika, also was eager to figure out her new country, quickly learning English and making friends in her citizenship classes.

"We were happy. How could I have felt unhappy with these people?" Malika said, referring to the Americans who befriended her. "They pushed me and said, 'Don't be scared, you're going to learn.' "

That carefree period ended with the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. Like other U.S. Muslims, the Farhanes said, they barely had time to grieve along with their fellow Americans - fellow New Yorkers - before they felt the backlash.

That same day, Farhane said, an angry man stormed into his store, threatening him. Another time, the parents called the police after a stranger unleashed a dog on one of the girls, whose hijab identified her as Muslim. Malika, who also wears a headscarf, gave birth to her youngest child the February after the attacks; she said the joy was overshadowed by worry that her newborn might be mistreated in the hospital.

"After 9/11, there was no life for us," Malika said of the fear that coursed through Muslim communities. "You walk in the streets but you're not walking, you're wooden. You don't even feel your body."

For a public-speaking class during his freshman year at college, only weeks after the attacks, Salah said, he wrote about how Islam doesn't condone violent actions like those of the hijackers.

"I was nervous - it was my first time speaking in front of the whole class, but I felt I had to do it," Salah said. "I had to let people know: This is where we stand."

In the aftermath, with the nation in mourning and the national security apparatus reeling from deadly intelligence failures, agents fanned out across the country to hunt for Islamist militants and their enablers.

Farhane's shop came under surveillance when an FBI informant - a Yemeni man named Mohamed Alanssi - told authorities that the owner held "radical views of Islam," according to court documents.

Starting that December, three months after the attacks, Alanssi began secretly recording conversations with Farhane, first inquiring about Islamic charities and gradually building up to asking him to help send money to militants overseas for "wireless communications and advanced weaponry," prosecutors said. Investigators also found contacts for suspected militants, including one who was linked to bombings in Saudi Arabia and Morocco, in an address book belonging to Farhane, prosecutors said.

In court papers, Farhane denied involvement in plotting terrorism and emphasized his lack of criminal record or ties to any militant group. At his first court appearance, Farhane insisted he was innocent, telling the judge, "I didn't do anything. This is my country. I love my country."

Throughout the case, Farhane's lawyers have attacked Alanssi's credibility, portraying the informant as a money-hungry "con man" who led their client into discussions of militancy that he never sought and made him uncomfortable. In 2004, Alanssi made his own headlines when he set himself on fire in front of the White House, saying that the FBI had failed to pay him for his services.

"Had Alanssi never come into his life, probably you never would have heard of Mr. Farhane," Farhane's then-attorney Michael Hueston said, according to court transcripts.

Fearing a worse outcome if he went to trial, Farhane said, he accepted the plea agreement on his attorney's advice. In his plea agreement, Farhane "admitted that in November and December 2001 he agreed with others to transfer money for mujahideen fighters in Afghanistan and Chechnya."

Farhane said his attorney told him he was facing a maximum sentence of eight years; instead he was given 13 years in prison and two years of supervised release.

Salah often says his father did the time inside but the family served on the outside. He lost a soccer team spot and, later, a police academy opportunity because of the stigma, he said. His mother grew paranoid and reclusive, trusting no one. When Muslim friends spotted them at the supermarket, Malika said, they abruptly turned their carts and went the other way.

Eventually, the family left Brooklyn and moved to more-affordable Newburgh, in an apartment for now because they're too scared to invest in a house with the case still in flux.

One of the sisters, a promising fencer who saw her dreams thwarted by the ordeal, has distanced herself from the family, trying for a fresh start. As painful as the estrangement is, Salah said, he understands his sister's decision. He admitted that he sometimes thinks of escape, too, picturing a Caribbean island where nobody knows about "the problem" and where he doesn't feel watched around-the-clock.

"He's 38 but his life is like an old man's," Malika said of her son, with sadness.

Listening to the recounting of the toll on his family, Farhane began to weep. Whatever his conviction, he said, why should his kids pay?

"I'm not a terrorist, but you want to say I'm a terrorist. OK, kill me!" Farhane said, his shoulders heaving, his head bowed in sobs. "But my son . . ."

After all they've endured, Salah said, it's hard to fathom the risk that comes with the pending appeal. Farhane has diabetes and uses a wheelchair because of a spinal injury - Salah said his dad's health isn't up to another round with the government.

"I'm hoping for this nightmare to be over," Salah said. "Just let us be. Whatever happened, happened. Just let us move on with our life."

- - -

Throughout the 1930s, '40s and '50s, thousands of people were denaturalized on ideological grounds, often for labor activism, said Amanda Frost, an American University law professor whose new book, "You Are Not American," examines the history of denaturalization.

Then, in a 1967 case, Frost said, "the Supreme Court said, 'You can't do this.' "

"But," she added, "there was a footnote."

The court left room for the government to revoke citizenship for fraud or error in the process, including under what Frost refers to as Cold War-era language that allows denaturalization in certain cases related to promoting communism, terrorism or totalitarianism.

In the five decades since, Frost said, Democratic and Republican administrations have used that wiggle room sparingly, typically denaturalizing fewer than a dozen people a year, most of them linked to war crimes and other violent offenses.

"They were the pretty extreme cases, and there were very few of them," Frost said. "And then came Jeff Sessions under [President Donald] Trump, and he said it clearly: He wanted to use denaturalization as an immigration-control effort."

The Justice Department division that handles denaturalization acknowledged a "staggering" increase in referrals, according to its budget plan for fiscal 2020.

The Open Society Justice Initiative counted 168 filings in 2017 and 2018. Of those, 11 involved terrorism, as in Farhane's case. A third of the rest - the largest category of filings - came from a controversial review of thousands of files to identify people who might have become naturalized despite past fraud or criminality. The report said the aggressive approach was accompanied by Trump administration rhetoric disparaging immigrants and Muslims.

It's almost impossible to pin down where most of those cases stand now and what the current number of pending cases is. The opacity is a main complaint of activists. More than 77% of the 168 cases were "either completely blocked online or contained documents that were inaccessible online," the Justice Initiative report said.

Frost and other denaturalization critics said they haven't heard of new cases filed since the change of administration, but they remain concerned that Trump-era efforts like the one against Farhane are proceeding. Frost, the Justice Initiative and other critics of the tactic have called for a moratorium.

"I'd like to see the [Biden] administration take denaturalization off the table as a tool for threatening and intimidating and excluding people who are now full members of the community," Frost said.

In November, federal appellate judges heard Farhane's argument that the guilty plea should be voided because his previous attorney, Hueston, failed to inform him of the citizenship risks involved or to negotiate a plea without immigration consequences. Reached by phone, Hueston said he had no comment. Farhane is currently represented by attorneys from the CLEAR clinic at the City University of New York School of Law and the private firm WilmerHale.

Farhane's legal team argued that it's absurd that a U.S. citizen would have fewer rights than noncitizens, who by law must be informed of immigration consequences before entering into plea agreements. Government lawyers countered that Hueston was under "no obligation" to advise Farhane on immigration matters.

Until the ruling comes, the lives of the Farhane family are on pause. Malika's father died recently, but she couldn't go to Morocco to be with her family. The siblings are reluctant to make travel plans or apply for new jobs. They're also anxious about the toll another separation would take on the family - the strain on their father's health and the burden on their mother, his caretaker.

Farhane said he understands the weight of the looming court decision, yet all his discussions of the future are fixed on the idea of remaining at home, in New York. He obtained a GED while in prison, and he dug out a photo that shows him proudly holding the certificate.

"I want to go to college now!" he said.

"He's got to win this case first," Salah said gently. "Or he's going to college in Morocco."