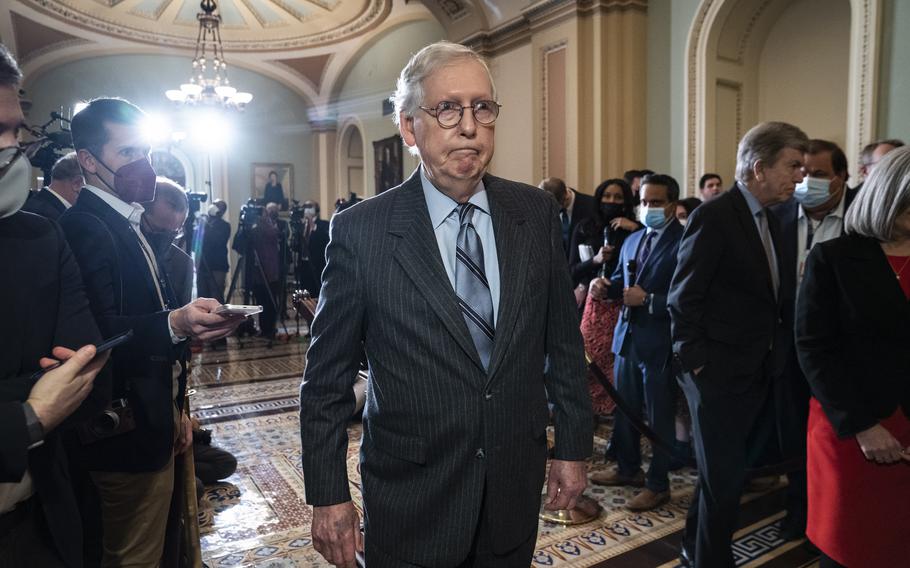

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., departs after a news conference following a weekly policy lunch on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. on Dec. 7. (Jabin Botsford/Washington Post)

WASHINGTON -- The Senate on Thursday advanced a bipartisan deal that paves the way for lawmakers to raise the debt ceiling, a move that positions Congress to stave off a catastrophic default ahead of a fast-approaching fiscal deadline.

Fourteen Republicans joined Democrats in overcoming a key procedural hurdle and setting up a final vote on the unusual arrangement, which doesn’t actually lift the cap - but rather tweaks Senate rules on a one-time basis so that lawmakers can tackle the matter more swiftly.

The House adopted the measure on Tuesday. The Senate is expected to hold a final vote to approve the measure before the end of the week, setting up President Joe Biden to sign a bill that also prevents a series of automatic cuts to Medicare. That could tee up Congress next week to raise the debt ceiling by trillions of dollars, covering federal spending obligations beyond the 2022 midterm elections - and defusing another potential last-minute conflict until after the political fate of the Capitol is decided.

But some Republicans expressed unease with the idea ahead of its passage, arguing they should not have provided any help to Democrats on the matter. The sharpest criticism came from former President Donald Trump, who attacked Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., this week for striking a deal - even though Trump himself had to rely on Democratic votes to raise the debt ceiling during his administration.

“The Dems would have folded completely if Mitch properly played his hand,” Trump said.

The bitterly divided Senate reached the compromise earlier this week, resolving a months-long battle between Democrats and Republicans that carried immense financial stakes - threatening, in the case of inaction, to plunge the economy into a recession.

McConnell initially had refused to supply GOP votes for a direct increase in the debt ceiling, which allows the U.S. to borrow money to pay its bills, as part of the party’s opposition to Biden’s broader spending agenda. Instead, he called on Democrats to address the measure on their own using the same legislative maneuver they intend to invoke to pass a $2 trillion initiative that aims to overhaul federal healthcare, education, climate and tax laws.

But Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., refused to take that route, arguing it was too politically risky so close to a deadline. Some Democrats also had hoped to suspend the debt cap, rather than raise it by a specific amount, to dodge political attacks entering the midterm elections. And many blasted Republicans for hypocrisy, since Democrats still aided Trump on the debt ceiling even when the now-former president pursued policies that his foes did not like.

The political stalemate nearly pushed the country to the fiscal brink in October, raising the potential for a global economic disruption, until McConnell relented and Republicans supplied the necessary handful of votes to adopt a short-term increase. That bought the U.S. government until December 15, at which point Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has predicted the country may not have enough money to cover its financial obligations.

Both sides consequently embraced the new arrangement as a political victory. Republicans won’t have to vote again on an actual, numerical increase to the debt ceiling, and Democrats can say they did so after some measure of bipartisanship and without risk of GOP obstruction. The fast-track procedure guarantees a vote on the increase set at a simple majority, with no opportunity for a filibuster.