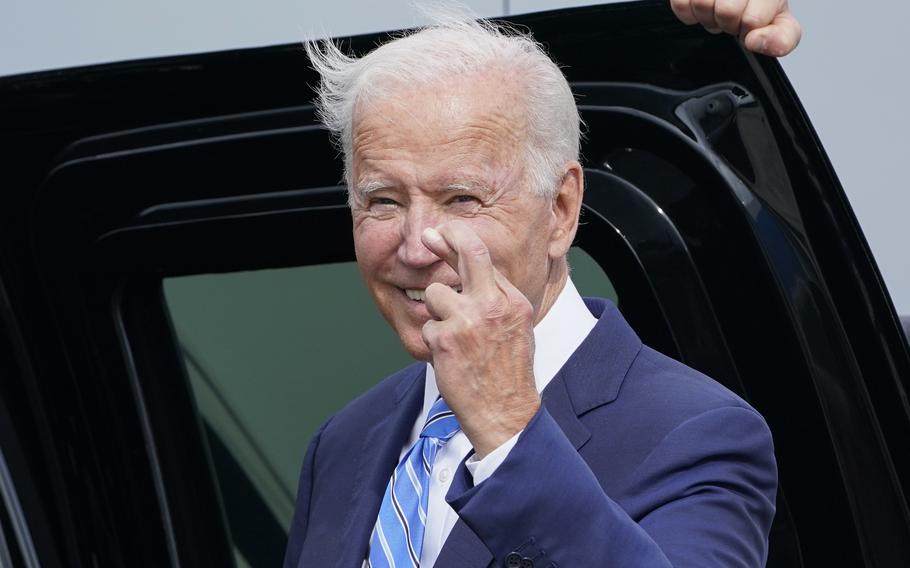

President Joe Biden crosses his fingers as he responds to a question about the short term debt deal as he arrives Air Force One at O’Hare International Airport in Chicago, Thursday, Oct. 7, 2021. While in the Chicago area, Biden will highlight his order to require large employers to mandate COVID-19 vaccines for its workers during a visit to a construction site. (Susan Walsh/AP)

WASHINGTON — The Senate late Thursday adopted a short-term measure to raise the country’s debt ceiling into early December, a move that could pull the federal government back from the fiscal brink even though it risked reigniting the high-stakes battle at the end of the year.

Lawmakers adopted the proposal strictly along party lines, with Democrats voting to lift the country’s borrowing cap by $480 billion and Republicans maintaining their steadfast opposition to it. The divide persisted even amid repeated warnings from President Joe Biden this week that inaction threatened to plunge the country into a new recession.

Republicans on Thursday did supply some of the votes necessary to advance the measure over key procedural hurdles in the otherwise deadlocked Senate. But even that task proved to be a significant political undertaking for GOP leaders, including Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., who faced criticism from his own members simply for making a deal with Democrats.

The resolution would end a tense few weeks of partisan warfare, during which Democrats tried repeatedly to suspend the country’s debt ceiling into 2022 — only to falter at the hands of GOP objections. McConnell led the blockade as part of the party’s broader campaign against Biden’s spending agenda, including a still-forming package of up to $3.5 trillion in spending that GOP lawmakers vehemently oppose.

But McConnell backed down late Wednesday, offering Democrats a temporary, roughly two-month reprieve. Republicans ultimately provided the 10 votes that Democrats needed to conclude debate a day later, though GOP lawmakers soon after voted against the actual increase to the debt ceiling itself. In ultimately allowing the measure to pass, some Republicans ignored a last-minute call to scuttle the deal by former President Donald Trump, who issued a statement shortly before the vote that blasted McConnell.

With a short-term solution in hand, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., hailed the development on the Senate floor late Thursday as a critical step toward “avoiding a first-ever, Republican-manufactured default on the national debt.”

“Republicans played a dangerous and risky partisan game,” he added, “and I am glad that their brinkmanship did not work.”

With a House vote expected soon, the measure is poised to head off a financial crisis with only days to spare ahead of the original Oct. 18 deadline. Failing to raise the debt ceiling by that date would have left the U.S. government unable to fulfill its financial obligations — including paying Social Security benefits to seniors, providing tax aid to families with children, or offering pay and other assistance to troops and veterans.

But the short-term deal also threatens to defer a bigger, more vicious battle between Democrats and Republicans until the final days of the year. The debt-ceiling increase covers federal borrowing only until about Dec. 3, the same day that funding for key federal agencies and programs is set to expire. That means Congress faces yet another deadline to stave off default and prevent a government shutdown, two urgent tasks that carry significant political and economic consequences in the case of failure.

Those tensions flashed Thursday in the hours before the Senate completed its work.

After McConnell offered Democrats a deal, Republicans grew restive about aiding their political adversaries. GOP lawmakers including Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina faulted McConnell, their own leader, for “folding” in the debate. In doing so, Graham and others signaled a wide-ranging war on the horizon as they intensify their opposition to Biden’s spending agenda and the government’s means to pay for it.

“I don’t blame Democrats for trying to do as much as they can,” Graham said. “I do blame us for not fighting when we can.”

For now, at least, the agreement over the debt ceiling would spare Washington from what experts broadly saw as a financial doomsday that could have rattled markets globally and plunged the United States into a new recession. Biden in recent days had pressured Congress to act, blasting Republicans from obstructing a long-term increase to the borrowing cap while huddling with the nation’s business leaders to further make the case for swift action.

To that end, financial markets appeared to reward news of the Senate deal, with the Dow Jones industrial average surging more than 330 points by the end of trading Thursday. The uptick only served to confirm the stakes in Washington’s fiscal stalemate, which earlier in the week raised the prospect that the U.S. could suffer a credit downgrade.

The debt ceiling allows the government to borrow money to pay its bills, since the country spends more than it collects through tax revenue. Raising the cap is a necessity that in the past had been a bipartisan affair: Democrats even joined with Republicans to address the issue repeatedly under Trump, who added $8 trillion to the debt during his time in office.

But Republicans over the past nine months have turned it into a political cudgel as they labor to fight back against Biden’s economic initiatives. The crux of the GOP opposition is a still-forming proposal to overhaul federal education, health care, immigration and climate laws, while raising taxes on wealthy Americans and corporations. Even though Democrats say the package is financed in full, Republicans argue it would add to the deficit even beyond the 10-year scope of the plan - prompting them to withhold their support for an increase to the debt ceiling.

“If the spending proposal they put forward passes, in a 12-month period, they will have spent $9.5 trillion,” Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, said during a speech earlier on the Senate floor. “It is wildly irresponsible. It is reckless.”

The Republicans’ opposition had for weeks frustrated Schumer and his fellow Democrats, who repeatedly pointed out that the debt ceiling covered past spending, including bipartisan initiatives to respond to the coronavirus pandemic enacted last year. But the entreaties failed to loosen the GOP blockade until McConnell offered a roughly two-month extension after meeting with his conference Wednesday.

The deal they championed a day later could carry federal borrowing until Dec. 3, but the deadline is only a rough estimate, according to Shai Akabas, the director of economic policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center. He said it ultimately is going to vary depending on how much the country spends and brings in through tax collection, which has been difficult to predict in recent months given the coronavirus pandemic.

“Nobody can know exactly how long that is going to last,” Akabas said, though he expressed a measure of confidence it could at least carry the country until early in December.

Eventually, though, the country is going to reach its borrowing cap and approach the precipice of a default - warranting another intervention on Capitol Hill. That risks reigniting the same battle that had pushed the Senate only 11 days away from what Biden has described as a “meteor” crashing into the U.S. economy.

Even as he brokered a deal, McConnell maintained an insistence Thursday that Republicans are not going to provide the 10 votes Democrats need to advance a longer-term measure to address the debt ceiling in the narrowly divided chamber, where most legislation requires 60 votes to progress. Instead, he said, Democrats must use reconciliation, a budgetary process that will allow them to move a proposal raising the borrowing cap on their own - a move that the party has rejected.

Schumer has refused to take that route, which he has described as “risky” because it could take too long to complete, putting the country at greater risk for default. On Thursday, he reaffirmed his opposition to reconciliation, seizing on the fact that McConnell had changed course after Republicans “finally recognized that their obstruction was not going to work.”

Privately, Democrats also acknowledge that reconciliation could open them up to uncomfortable political votes and attacks, especially because it requires them to raise the debt ceiling by a specific amount rather than suspending it outright.

Foreshadowing the fight ahead, McConnell took to the floor Thursday to herald their deal as a way to “spare the American people any near-term crisis.” But he also repeated they must use reconciliation, unleashing renewed attacks on Democrats for their “reckless taxing-and-spending spree” in the process.