WWL hosts Tommy Tucker, left, and Newell Normand during their early-evening show. Normand, the former sheriff of Jefferson Parish, usually hosts an evening show and has been paired with Tucker, the morning host, for hurricane coverage. (Holly Bailey/Washington Post)

NEW ORLEANS — The power was slowly flickering back on across the city a week after Hurricane Ida dealt a catastrophic blow to the energy grid, leaving hundreds of thousands of people without power, but Nettie needed help.

Her apartment building along St. Charles Avenue in central New Orleans was still dark. With the heat index in the triple digits, there was no air conditioning, and the residents - most of them seniors who could barely get down the stairs - were running out of bottled water and food.

Desperate, Nettie picked up the phone last Saturday afternoon - not to call the city, which had advised residents in need to go to local cooling centers for ice, food and shelter. Instead, she called WWL, a New Orleans talk radio station.

"Somebody has to do something," Nettie pleaded, her call broadcast live on WWL. "That's why I called y'all."

Within seconds, the station's phone and text lines had blown up with offers of help, including from a Navy veteran who said he was loading up his truck with ice and water. "People call and say they need help, and listeners go help them," said Dave Cohen, the station's news director. "And that is amazing."

In normal times, the hosts at WWL spend their days debating politics, sports or whatever is in the news. But in storm season, WWL is known among locals as the "hurricane station," often providing the only link between listeners stranded without power and the outside world.

Ida's tear across the Gulf Coast last week rendered almost all modern communication useless. With no power, there was no television, and with many cellular towers down, phone service was spotty, if it worked at all. That meant no Twitter, streaming apps or news websites. But one medium endured: good old-fashioned radio.

And WWL was ready. Last week, as Ida took aim at the Louisiana coast, 19 station employees - including on-air hosts, producers and engineers - moved into WWL's studios in an office building along Poydras Street to ride out the storm. They kept the station on-air 24 hours a day to cover the aftermath, as they have done for every major hurricane that has blown through the region in recent memory.

Hosts and producers moved into the WWL offices to stay on the air during and after Hurricane Ida. (Holly Bailey/Washington Post)

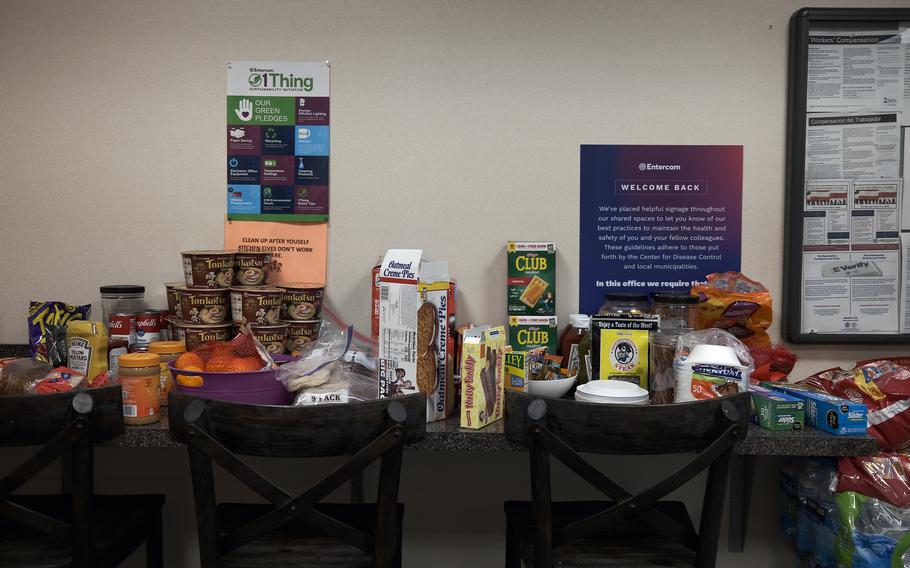

The skeleton crew slept on air mattresses crammed into offices and extra studios, relying on a towering stockpile of snacks and nonperishable food stored in the office pantry to get them through the storm and its aftermath.

The hosts did double shifts, working three or four hours during the day and then again at night as part of a round-the-clock coverage plan designed not only to get the news out, but also to be a source of support for a region where many remain deeply traumatized by the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina 16 years ago, when flooding overtook much of New Orleans and left nearly 1,200 people dead across Louisiana alone.

"We're trying to be there for people. Because this is our community, too," said Diane Newman, the station's longtime operations and program director, who helped keep the station on air during Katrina and was among those who spent days living in her office after Ida. "Until the power comes back on, fully, we're going to be there covering this storm."

Each day, the station has fielded thousands of calls from listeners sitting in their dark, damaged homes, many of whom spoke of listening in with their old battery-powered radios. "I've had this thing since the '70s," one woman said, explaining how she had to dig in a closet with a flashlight to unearth her radio.

Sen. John Neely Kennedy, R-La., one of the myriad public officials who have called in to the station in recent days to get information out to constituents, told a harrowing story on air of riding out the storm at his home in Madisonville, La., along the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain, where the winds were so fierce he "found Jesus three or four times that night."

"I found one of my old radios I used to listen to in college and . . . I am not just saying this, I turned it to WWL," Kennedy said. "You're like the only source of information right now."

"Sometimes it's just back to the basics. And for many of you, that's where we are," WWL host Scott "Scoot" Paisant told his listeners during one intense hour in which people tearfully called the station, worried they might not survive the intense heat and deteriorating conditions.

"This is one of those moments that just so accentuates the immediate intimate relationship between radio and listeners, and we are here for you," Paisant said. "We are here with you. . . . You're going to be okay."

The format has been loose. Callers worried about relatives in flooded parishes where communications have been down have phoned in to put out the call for information. "Anyone hear anything about Galliano? Call us," host Tommy Tucker told listeners, one of several cities he shouted out during coverage.

Tucker, a longtime New Orleans radio personality who usually anchors the station's morning show, spent more than eight hours a day on air in the first five days after the storm, including co-anchoring an evening show with Newell Normand, a former Jefferson Parish sheriff. The men took calls on everything from how to run a generator properly to where to find gas.

Normand, who was once rumored to be a possible candidate for governor, worked his contact list, often getting top political officials on the phone to press them about what they had heard about FEMA assistance and other state and federal aid, including for areas along the bayou that had been virtually wiped off the map by Ida's winds and storm surge.

"People are hurting," Normand told a local Federal Emergency Management Agency official, who joined the show to take calls from listeners who complained that they had been denied federal aid even as they couldn't reach their insurance companies. "What is FEMA doing?"

Sometimes people just wanted to talk. On Friday, a woman called in and told Tucker about riding out the storm with her chicken. "Wait. A chicken in the house?" Tucker asked, prompting the woman to put the hen on the phone, where it let out a faint cluck.

"OK, things are getting a little crazy," Tucker said with a chuckle.

Inside the eighth-floor studio on Friday, it had been almost a week since employees had moved in. Some walked around in shorts and T-shirts, instead of the usual business-casual office attire. In a spare studio, a plastic bag with a toothbrush and toothpaste sat near a microphone, a twin-size air mattress with rumpled sheets on the floor below.

Powered by a building generator, the studio was a cool oasis compared with the oppressive heat of the city outside. Only a few had left the station, some to quickly check on their homes and make sure they were still standing after Ida's winds - which measured upward of 150 mph at times - caused damage across the city.

Paisant, a former rock DJ with a butter-smooth voice and a poof of blond hair who has worked in New Orleans on and off for 50 years, had moved into a new apartment the week before, racing to beat rain that developed as Ida approached the coast. But he hadn't spent one night in the apartment and had left the studio just once - to make sure the new place still had its roof. "I didn't know what to expect, but everything was OK," he said.

A stockpile of food inside WWL's kitchen. (Holly Bailey/Washington Post )

When the staff moved into the WWL offices Aug. 28, the day before Ida made landfall, it was the first time many had seen one another in over a year. Most employees had been anchoring and producing their shows from home studios because of the coronavirus pandemic.

"It was like this happy reunion, but also a worrisome reunion because we didn't know what to expect," she said.

Sixteen years ago, the staff had undertaken similar measures ahead of Katrina's arrival, moving into their studios, which at the time were next to the Superdome. As that storm moved in, bricks and other debris began to pelt the building, forcing the staff to board up and brace the studio's glass windows live on the air. But it wasn't enough.

When the windows of the studio blew out, engineers rushed to set up a temporary interior studio down the hall. Newman recalled how they frantically assembled a microphone on wheels and slowly moved the host and all of his wires down the hall. "It was like he was on an IV," she recalled.

Most of the staff ultimately evacuated, as floodwaters began to pour into New Orleans through damaged levees, and operations were moved to Baton Rouge. But the station never stopped broadcasting.

As Ida moved into the city last week, the winds howled and shook the building. But every window stayed in place. When the building lost power, the generator kicked in - keeping the station on air in a city that had gone entirely dark.

The staff kept working. "I've slept maybe two or three hours a day," Tucker said, as he and Normand walked toward the studio five days after the storm. "But you just keep going because this is what we do."

At the microphone, Paisant was packing up and preparing to sign off. In his office down the hall, decorated with backstage passes and old concert stubs from his former gig as a rock DJ, he would soon queue up a song from the Cure - "Lovesong" - its melody echoing through the office that had become his temporary home.

But right then, as he prepared to sign off for the night, it was the adoration he felt for his hometown that was on his mind, the devotion that had kept him working days and nights in service to the listeners at home.

"This is Scoot," he said. "Love you, New Orleans."