When he crossed the Pacific Ocean in a hot-air balloon in 1991, Richard Branson ended up so far off course that instead of touching down in Southern California, he crashed landed on a frozen lake in Canada.

His balloon ride across the Atlantic four years earlier had been just as perilous, forcing Branson to bail out by jumping into the sea after writing a farewell note to his family in case he didn’t survive.

Over the years, the brash British billionaire has embarked on all sorts of wild adventures, from the dangerously ill-conceived to the merely zany — from attempting a powerboat speed record across the English Channel in seas so choppy it “was like being strapped to the blade of a vast pneumatic drill,” as he wrote in his memoir; to dressing up as a bride to launch his ultimately unsuccessful foray into the wedding gown industry.

Now, the one-man publicity circus, as he has been called, is preparing for what would be the biggest stunt of all: A rollicking ride to the edge of space in the spaceplane developed by Virgin Galactic, the venture he founded in 2004 that he vowed would become the world’s first “commercial spaceline.”

Virgin Galactic announced this week that Stephen Colbert would host the live-stream broadcast of the event, now scheduled for Sunday, though weather and last-minute technical problems could force a delay. And the company also intends to use Branson’s flight as a catalyst to reopen ticket sales for its space tourism business. It had previously cost $250,000 for the flight, which would allow passengers to experience a few minutes of weightlessness. But when the tickets go back on sale, the price is expected to jump to about $500,000, according to analysts.

Like Branson’s previous exploits, the flight from Virgin Galactic’s Spaceport America in New Mexico will be as much theater as adventure, designed to sell tickets as well as to celebrate the commercialization of human space exploration. But that is to be expected from the man who made his start by signing the Sex Pistols to his record label and who’s lived by the motto, “screw it, let’s do it.”

Last week, Branson — who’ll turn 71 on July 18 — ensured his spaceflight attempt would get even more publicity when he announced that he would accelerate the test flight schedule Virgin Galactic had previously announced so that he could fly earlier.

The company had planned to fly a test flight with four crew members in the cabin, and then fly Branson. But after Jeff Bezos announced he would fly on his company’s spacecraft to the edge of space on July 20, Branson jumped the line and said he would board Virgin Galactic’s next space flight and — conditions permitting — beat Bezos by nine days.

In making the announcement, Branson simultaneously reveled in the attention it generated while downplaying any competition. He told The Washington Post, which Bezos owns, “I completely understand why the press would write that.” He added that it was just “an incredible, wonderful coincidence that we’re going up in the same month.”

But when asked about a rivalry with Bezos on CNBC, he couldn’t help himself, saying, “Jeff who?”

Branson’s antics elicited a strong response from Bezos’ Blue Origin, which prides itself on being quiet, letting its actions speak for themselves and focusing on its customers instead of its competitors. Bob Smith, Blue Origin’s CEO, issued a statement last week wishing Branson well but also pointing out that Virgin Galactic is “not flying above the Kármán line, and it’s a very different experience.” The Kármán line, at 100 km or 62 miles above sea level, is an internationally recognized threshold for where space begins. Virgin Galactic flies to just over 50 miles, where the Federal Aviation Administration will award crew members astronaut wings.

On Twitter Friday, Blue Origin pressed that point again and took a swipe at its competitor, saying Virgin Galactic’s spaceplane doesn’t have an escape system, and that it has only reached its maximum altitude three times, compared with 15 for Blue Origin’s New Shepard capsule. The company also pointed out that its windows were larger, providing a better view, and it alleged that Virgin Galactic’s hybrid rocket engine is far more harmful to the environment.

Whether it was to beat Bezos or not, the change in the test flight schedule has concerned many in the spaceflight community who said they hoped Virgin Galactic wasn’t sacrificing safety for speed.

Wayne Hale, a former NASA flight director who was the space shuttle program manager and has extensively discussed the risks inherent in human spaceflight, wrote on Twitter: “Talk about schedule pressure! Hope nobody cuts any corners.”

In an interview last week, Virgin Galactic CEO Michael Colglazier, said the company had done just the opposite, undertaking a thorough review of its third human spaceflight mission in May.

“We hit all of our test objectives,” he said. “We took the time to do the studies, and it was an excellent success. That means we’re ready for the next flights in our test program.”

Given that the last test flight went so well, he said the company decided that Branson could choose to stay on his original flight or move up one. “Guess which one he chose?” Colglazier said.

Branson also has said that he’s confident the vehicle is safe and that he’s looking forward to the experience. “I’ve been itching to go, and they said they wanted somebody to properly test the astronaut experience,” Branson said. “And I was damned if I was going to let anyone take that seat.”

Unlike traditional rockets that launch vertically from launchpads, Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo Unity, as it is called, is tethered to the belly of a mother ship, which carries it to about 45,000 feet. The spaceplane is then released, the pilots fire its engines, and it goes screaming up through the sky until it reaches the edge of space. It then reorients itself, falls back toward Earth and glides to a runway landing.

It’s a system originally designed by Burt Rutan, the legendary aircraft builder, whose SpaceShipOne in 2004 became the first commercial spacecraft to reach the threshold of space. That spacecraft carried just one person, though, the pilot.

SpaceShipTwo has two pilots as well as a crew of four, and Branson’s flight would be the first time the company has attempted a spaceflight with all six seats filled.

To get to this point, Branson and Virgin Galactic have traveled a long way, an up-and-down journey filled with setbacks and delays as well as triumphs.

After years of technical problems that delayed commercial flights — which Branson had once hoped would happen as early as 2007 — the company seemed to be making real progress in 2014. But late that year, the spacecraft came apart during a test flight when one of the pilots prematurely unlocked a device designed to reorient the spacecraft once it is in space. One of the pilots, Michael Alsbury, who was 39 and had two young children, was killed in the accident, and the other, Peter Siebold, suffered serious injuries after parachuting to the ground.

The National Transportation Safety Board blamed the catastrophe on human error but also said the design was flawed. After the accident, Virgin Galactic took over full control of the test program and design, which had been overseen by Scaled Composites, a Northrop Grumman subsidiary.

Shaken, Branson considered giving up, saying human spaceflight was too difficult and dangerous. But in the end, he decided that the risk was worth it and that the company would bounce back, stronger and more resilient.

The company made some safety enhancements to the ship, and in late 2018 made it to space for the first time. Branson, watching from the side of the runway, broke into tears when the announcer said the spacecraft had passed 50 miles above sea level. The company did it again in 2019, this time with a crew member, Beth Moses, the company’s chief astronaut instructor, on board.

The third flight was delayed while the company made more safety enhancements — a seal running along a wing stabilizer had come undone during the previous flight. The company moved operations from California to New Mexico, went public through a merger with a New York investment firm and hired a new CEO and leadership team.

The company attempted another flight in December of last year, but it was aborted just as the engine fired when electromagnetic interference from a flight computer system caused the engine to shut down. The company said it resolved the issue and completed its third human spaceflight mission in May.

That opened the door for Branson to go. And if all goes well, the company plans to begin commercial operations as well, flying the 600 or so people who have put down significant deposits and, in some cases, have been waiting years to go.

Branson said he was very much looking forward to “looking straight back down at the Earth through those windows.”

He added that “we’ll finally be able to get our long-suffering customers up there and give them a chance to go as well.”

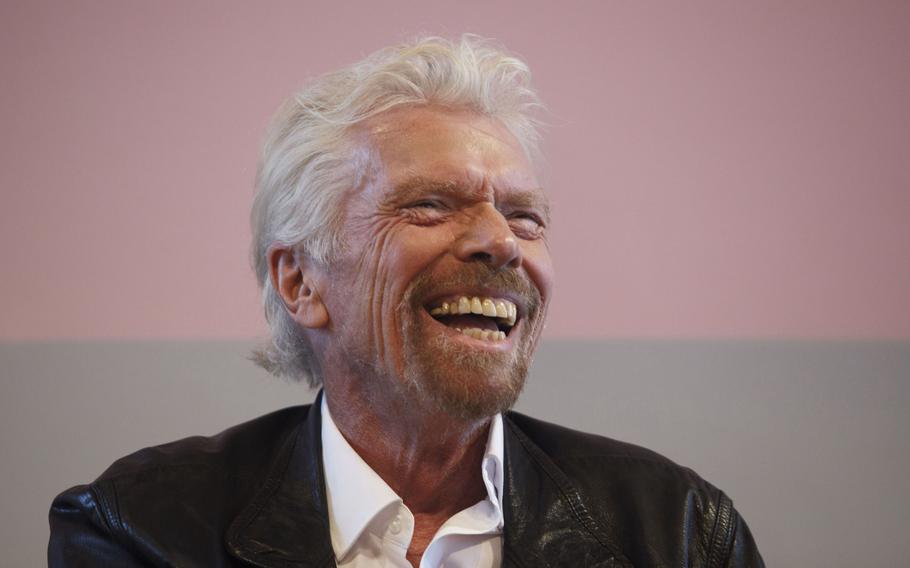

Billionaire Richard Branson, founder and president of Virgin Atlantic Airways, at the Peres Center for Peace in Tel Aviv, Israel, on Oct. 24, 2019. (Kobi Wolf/Bloomberg)